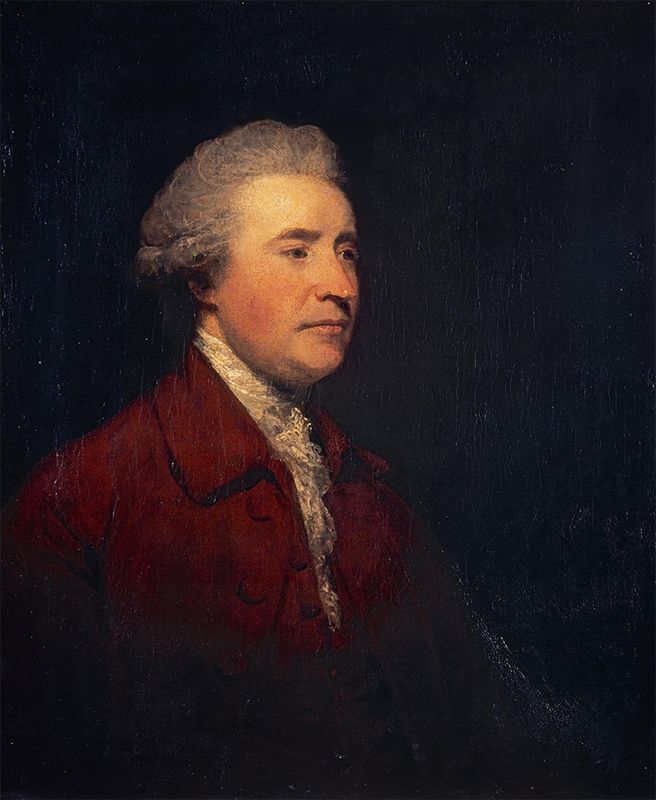

Edmund Burke (1729–1797)

Note: the 19th- and early 20th-century biographies below preserve a historical record. A new biography that reflects 21st-century approaches to the subjects in question is forthcoming.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

BURKE, EDMUND (1729–1797), statesman, the second son of Richard Burke, an attorney resident in Dublin, appears to have been born—for the exact date is not absolutely certain—on 12 Jan. 1729, N. S. There is no ground for the often-repeated statement that his family belonged to Limerick. His father was a protestant; his mother, whose maiden name was Nagle, was a Roman catholic. Although brought up in his father's religion, Burke was accustomed to look on Roman Catholicism as the religion of many he loved, and thus early learnt the lesson of toleration. This lesson must have been still further impressed on him when, in 1741, he was sent to a school at Ballitore, co. Kildare, kept by Abraham Shackleton, a member of the Society of Friends, from whom he declared that he gained all that was really valuable in his education. With Shackleton's son Richard he formed a friendship which lasted through life. In 1743 he entered Trinity College, Dublin, and remained there until 1748. He seems to have studied diligently, but in a desultory fashion, taking up various subjects with eagerness, and dropping each in turn for some new pursuit (Works, i. 12). He made himself familiar with Latin authors, and especially with Cicero, 'the model on which he laboured to form his own character, in eloquence, in policy, in ethics, and philosophy' (Sir P. Francis to Lord Holland, p. 17). Although it has been asserted that he knew little of Greek, a letter of C. J. Fox states that he knew as much of that language as men usually do who have neglected it since their school or college days, and that the writer had heard him quote Homer and Pindar (Dilke, Papers of a Critic, ii. 312). He gained a scholarship by examination in 1746. His letters to Richard Shackleton during this period are such as any earnestly minded and ambitious youth might have written, and the verses sent with them do not show any special power. As in after life, his favourite recreation was to be among trees and gardens. He took his B.A. degree in the spring commencements of 1748, having been entered at the Middle Temple the year before, and in 1750 came up to London to study law. He did not apply himself steadfastly to work. His health was weak, and he seems to have spent much time in travelling about in company with his kinsman William Burke [q. v.], staying at Monmouth, at Turley House, Wiltshire, more than once at Bristol, and at other places. We scarcely know anything of this period of his life; for with the exception of one rather obscure fragment (Prior, 41), there is not a letter of his extant between 1752 and 1757. He seems to have broken off all communication even with R. Shackleton, for writing to him, 10 Aug. 1757, he says that he sends him a copy of his 'Philosophical Inquiry' 'as a sort of offering in atonement,' and speaks of himself as having been 'sometimes in London, sometimes in remote parts of the country, sometimes in France, and shortly, please God, to be in America' (Works, i. 17). In 1756 he was lodging over a bookseller’s shop near Temple Bar. He appears to have frequented the theatres and one or two debating societies, and to have made the acquaintance of some famous men, such as Garrick, with whom he formed a warm and lasting friendship.

Literary work was more to Burke’s taste than legal study. He was never called to the bar, and the rejection of the profession for which he was designed angered his father, who in 1755 withdrew either wholly or in part the allowance of 100l. a year he had hitherto made him. Burke was thus forced to depend on literature for his livelihood. He had probably already written his ‘Hints for an Essay on the Drama,' a short piece which remained unpublished until after his death. In 1756 he produced two works which at once gained him a high place in literature. The first of these, his ‘Vindication of Natural Society, in a Letter to Lord ——, by a late Noble Writer,' was called forth by the publication of Bolingbroke’s works in 1754, and is a satirical imitation both of his philosophy and his style. Applying Bolingbroke’s arguments against revealed religion to an examination of what is ironically called ‘artificial society,’ Burke exhibits the folly of demanding a reason for moral and social institutions, and, with a foresight which was one of the most remarkable traits of his genius, thus early distinguished the coming attack of rationalistic criticism on the established order, and marked it as his special foe. The lofty style and eloquent diction of Bolingbroke were so skilfully imitated in this little pamphlet, that even such critics as Warburton believed the satire to be a genuine work, and the careful study of the original left its mark on the style of the imitator (Morley, Life of Burke). 'The Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas on the Sublime and the Beautiful’ had been begun before Burke was nineteen, and had been laid aside for some years. This treatise, strange as some of its dicta are, was held by Johnson to be ‘an example of true criticism’ (Boswell, Life, iii. 91), and seemed to Lessing well worthy of translation. Burke‘s father was so pleased with this book that he sent him 100l. (Bisset, 36). Burke never ceased to take a warm and discriminating interest in all artistic matters, and is said to have ‘embraced the whole concerns of art, ancient as well as modern, foreign as well as domestic’ (Barry, Works, ii. 538). He was still in weak health, and accepted an invitation to stay with his physician, Dr. Nugent, in order to escape from noisy lodgings. He married the doctor's daughter Jane in the winter of 1756–7. According to one account, Burke became an inmate of Dr. Nugent’s house while on a visit to Bath, where the doctor lived before he removed to London. Up to the time of her marriage Mrs. Burke was a Roman catholic, but she conformed to her husband's religion. Burke’s marriage was a happy one; his wife was a gentle–tempered woman, and he was noted among his friends for his ‘orderly and amiable domestic habits’ (Boswwll, Life, vii. 250). They had two sons: Richard, born 1758, and Christopher, who died in childhood.

Early in 1757 Burke published ‘An Account of the European Settlements in America.' As regards the authorship of this book, he told Boswell, ‘I did not write it. I will not deny that a friend did, and I revised it.’ ‘Malone tells me,’ adds Boswell, ‘that it was written by William Burke, the cousin of Edmund, but it is everywhere evident that Burke himself has contributed a great deal to it’ (Boswell, Letters to Temple, p. 313). The early sheets of ‘The Abridgment of the History of England’ were also printed in this year, though the book itself was not published until after Burke’s death, The crisis of the war in 1758 probably moved Burke to undertake the production of the ‘Annual Register,' the first volume of which appeared in 1759. For this work Dodsley aid him 100l. a year. He never acknowledged his connection with this publication, and the amount of his contributions to it has never been ascertained. He evidently continued to write the ‘Survey of Events’ for some years after he entered political life, and even after he ceased to write it, about 1788, probably inspired and directed its composition. His literary successes brought him into society. Mrs. Montagu, writing in 1759, describes him as free from ‘pert pedantry, modest, and delicate' (Letters of Mrs. E. Montagu, iv. 211). He was now residing with his father~in-law in Wimpole Street. He was in want of money, and was anxious to obtain the appointment of consul at Madrid. His cause was espoused by Dr. Markham, head-master of Westminster (afterwards archbishop of York), who prevailed on the Duchess of Queensberry to write to Pitt on his behalf (Prior, 62). The application was rejected, and Pitt was thus the means of keeping his future antagonist from leaving the field of action.

Before the end of 1759 Burke was introduced by Lord Charlemont to William Gerard (‘Single-speech’) Hamilton (Memoirs of Lord Charlemont, i. 119). He engaged himself as a kind of private secretary to Hamilton, and the work his employer required of him shut him out from all authorship save in the ‘Annual Register.' On the other hand, his intimacy with Hamilton made him known to many persons of importance. In 1761 Hamilton was made secretary to the Earl of Halifax, and Burke went with him to Ireland. It was the year of the first outbreak of Whiteboyism, a movement which he attributed to local grievances, and not to political discontent (Works, i. 21). The policy of repression pursued by the government led him, probably about this time, to draw up some reflections on the penal code which remained unfinished, and were published after his death (ib. vi. l). After a year in Dublin he returned to England with Hamilton, who in the spring 1763 obtained for him a pension of 300l. a year. Burke, however, felt that he was doing himself an injustice in giving up all his time to Hamilton's service, and wrote plainly to his patron that he must be allowed some time for literary work, and that he could only accept the pension on that condition. In the autumn he was again in Ireland, but in May 1764 Hamilton lost his office, and Burke returned to live with his father-in-law in Queen Anne Street. Before he left Ireland he drew up an address to the king setting forth the hardships suffered by the Irish catholics, and left it with a friend. Fourteen years afterwards this document was forwarded to George III, and, it is said, did much towards reconciling him to the first instalment of religious toleration in Ireland (ib. i. 376). On his return to England Burke became a member of the club founded in the spring of that year at the Turk’s Head in Gerrard Street. His powers of conversation mads him one of its chief ornaments. Johnson declared that if you met him for the first time in the street, after five minutes' talk ‘you would say, This is an extraordinary man. He is never,' he said, ‘humdrum, never unwilling to talk, nor in haste to leave off.' ‘Burke’s talk,’ he remarked on another occasion, ‘is the ebullition of his mind; he does not talk from a desire of distinction, but because his mind is full.’ Partly perhaps because he thus spoke out of the abundance of his heart, he was not witty. ‘No, sir,’ Johnson said, ‘he never succeeds there. ’Tis low, ’tis conceit’ (Boswell, Life, iv. 23, 225). He had the power of making men love him. His friendship with Garrick, Reynolds, and Johnson was in each case only broken by death. To Garrick he looked in time of need. Reynolds made him one of his executors, and left him 2,000l. Johnson, when on his deathbed, said to him, ‘I must he in a wretched state indeed when your company would not be a delight to me.' Anxious to have such a man as Burke at his disposal, Hamilton offered him a yearly sum on condition that he devoted himself, wholly to his service. Burke refused to sell himself, and his jealous patron broke off his connection with him. Indignant at his imperious conduct, Burke, in April, threw up the pension he had received through his intercession. During the period of his poverty he had cared little for money. However small his means were, he was always ready to give to others. While still struggling unknown in London, he met Emin, the Armenian adventurer, then friendless and in distress, and took him to his lodgings. Offering him half a guinea, he said, ‘Upon my honour, this is all I have at present; please accept it’ (J. Emin, Life and Adventures, 90). By 1765, however, it is probable that his prospects were brighter. During his stay in Ireland in 1763 he befriended James Barry, the painter [q. v.], brought him back with him to London, and in 1765 undertook to defray the greater part of the expense of sending him abroad to study (Barry's Works, i. 9–26). This seems to show that he had by this time some command of money, and certain notices, which are given below, as to the means of his family in 1766, render it probable that his brother and cousin had already embarked in speculation. In after days Burke saved Crabbe from a debtors’ prison, lodged him in his own house, treated him as an honoured guest, and used his interest to gain the poet a livelihood.

In July 1765 Lord Rockingham, who had just been appointed first lord of the treasury, made Burke his private secretary. This appointment he owed to the good offices of his kinsman William Burke; it was the signal for all who grudged the rise of a man unconnected with any of the great houses to spread evil reports of him, and it was not long before the old Duke of Newcastle hurried to Lord Rockingham primed with slanders. The minister had been deceived; his new secretary was not merely an Irish adventurer, but a papist and a jesuit from St. Omer. Rockingham frankly told Burke what he had heard, and the spirit with which the secretary behaved won his entire confidence (Memoirs of Lord Charlemont, ii. 231). From this time onwards he looked on Burke as a personal friend as well as a useful ally. He advanced him large sums of money, and at his death directed that his bonds should be destroyed (Works, i. 504). These bonds are said to have been for 30,000l. The report that Burke was a catholic was not allowed to die out. Utterly without foundation as it was, the accusation wus too mischievous to he dropped by the pensioners of the powerful cliques of nobles and place-men, who were soon to have cause to hate and fear him, and sometimes supported by idle tales and often in its simple falsity it was brought against him over and over a in all through his life. Before the end of the year William Burke, then under-secretary to Conway, arranged with Lord Verney, with whom he was connected in business tmnsactions, that Burke should be returned to parliament for Wendover, one of the earl’s boroughs, while he himself was elected for another. Burke was returned on 28 Dec. (Members of Parliament, ii. l23), and took his seat 14 Jan. 1766. Johnson presaged his friend’s successful career: ‘Now we who know Mr. Burke,’ he said, ‘know that he will be one of the Hrst men in the country’ (Boswell, Life, vi. 80). His first speech was made on 27 Jan., on a motion that the petition sent from the American Congress should be received by parliament. Contrary to the opinion of the majority of the ministerial party to which he belonged, he argued that the petition should be received on the ground that it was in itself an acknowledgment of the right of the House (Walpole, Memoirs of the Reign of George III, ii. 272; Bancroft, Hist. of U. States, iii. 551). A week later he acted with his party by speaking in favour of the Declaratory Resolutions. While allowing the right of taxation, he recommended a temponsing policy. Now, as ever, he refused to treat politics as an abstract science, and held duties rather than barren rights to be the true basis of political action. ‘Principles,' he said, ‘should be subordinate to government.' He had now established his position amor? the leading men of the house. ‘He made,’ Johnson wrote, ‘two speeches on the repeal of the Stamp Act, which were publicly commended by Mr. Pitt, and have filled the town with wonder’ (Boswell, Life, ii. 321). In the course of a debate held during the same session on the restriction on American trade Burke exhibited his attachment to the principle of commercial freedom, and bitterly jeered Grenville ou his reverence for the Navigation Act (Walpole, George III, ii. 316).

Burke seems by this time to have overcome his former weakness of constitution, though he suffered from a sharp attack of illness during his first session. Tall and vigorous, of dagniiied deportment, with massive brow an stern expression, he had an air of command. His voice was of great compass; his words came fast, but his thoughts seemed almost to overcome even his powers of utterance. Invective, sarcasm, metaphor, and argument followed hard after one another; his powers of description were gorgeous, his scorn was sublime, and in the midst of a discussion of some matter of ephemeral importance came enunciations of political wisdom which are for all time, and which illustrate the opinion that he was, ‘Bacon alone excepted, the greatest political thinker who has ever devoted himself to the practice of English politics’ (Buckle, Civilization in England, c. vii.) Although he spoke with an Irish accent, with awkard action, and in a harsh tone, his ‘imperial fancy’ and commanding eloquence excited universal admiration. No parliamentary orator has ever moved his audience as he now and again did. His speech on the employment of the Indians in war, for example, is said at one time to have almost choked Lord North, against whom it was delivered, with laughter, and at another to have drawn ‘iron tears down Barré's cheek' (Walpole to Mason, 12 Feb. 1778; Letters, vii. 29). Unfortunately, his power over the house did not last ; his thoughts were too deep for the greater part of the members, and were rather exhaustive discussions than direct contributions to debate (Morley, Life, 209), while the sustained loftiness of his style and a certain luck of sympathy with his audience marred the effect of his oratory. His temper was naturally hasty, and he was deficient in political tact (Correspondence of C. J. Fox, i. 86). Jealously excluded from office, with narrow means and disappointed hopes, he became soured and violent, and as die encountered neglect and rudeness, lost his dignity while he retained his vehemence. He wrote as he spoke, not in any set literary fashion, but with ease and vigour, taking Dryden's prose for his model, while at the same time he was under the influence of Bolingbroke’s rapid style (Memoirs of F. Horner, i. 348). Neither in speaking nor writing did he avoid using' wor of foreign origin, and he constantly heightened the effect of his appeals by a quick transition from the sonorous expression of lofty sentiments to a terse saying clothed in homely English. In some of these sayings, indeed, he overpassed the bounds of good taste, while his loftier heights were not always free from bombast. His utterances, however, were not all declamatory. When occasion demanded, he spoke with quiet dignity, and some of his writings, such as the Historical Surveys in the ‘Annual Register,' his protests written for the lords, and even certain of his pamphlets, are models of statesmanlike expression.

On the resignation of the Duke of Grafton, one of the secretaries of state, it was evident that the Rockingham administration would shortly come to an end. Conscious of the advantage he would gain by holding a high office even for a little while, Burke was ambitious and self-confident enough to imagine that he might be chosen to fill the duke’s place for the short time of office that yet remained to his party. A seat at the board of trade was suggested, perhaps actually offered to him. That, however, was not his object, and he declined it (Works, i. 154; Chatham Correspondence, iii. 111). On 7 June 1766 Rockingham was summarily displaced; Grafton came into office, and Burke’s hopes perished. Indignant at the treatment is leader had received, he set forth the services of the outgoing ministers in a little pamphlet called ‘A Short History of a Short Administration,' and heightened its effect by a letter in the ‘Public Advertiser' ironically purporting to answer it (Ann. Reg. 1765, 213).

In the summer of 1766 Burke visited Ireland, and spent a short time with his mother at the house of his sister Juliana, the wife of Mr. French of Loughrea. While there he received the freedom of the town of Galway. He also visited a small estate called Clohir on the Blackwater, which he had received the year before on the death of his brother Garrett, an attorney. It has not been satisfactorily ascertained, how this estate came into the hands of Garrett Burke. It is stated that it was conveyed to him by a catholic family in order to evade the rigour of the penal laws, and that he claimed it for himself (Dilke). Burke in 1777 was threatened with a lawsuit to recover this property. His legal position was evidently safe. He declared in a letter addressed probably to the solicitor of the claimant, Robert Nagle, that he had no reason to think that there had been any original wrong in the matter, and that he could not, in justice to his brother’s memory, admit the claim, but that he was willing to do what he could ‘voluntarily and cheerfully’ for the Nagle family (New Monthly Mag. 1826, xvi. 153). In 1790 he sold Clohir to Edmund Nagle for 3,000l.

On Burke's return from Ireland Lord Chatham wished to attach him to his administration. He insisted, however, on following Rockingham, though Grafton declared that ‘he would not have been obdurate if his demands had not been too extravagant' (Walpole, George III, ii. 378). In the course of the next session Burke forwarded the interests of his native land by opposing a motion to forbid the importation of Irish wool, and his speech on this occasion was rewarded by the grant of the freedom of Dublin. An attack on the East India Company on 9 Dec. 1766 called forth what Walpole declared to be ‘one of his finest speeches,' in which he ridiculed Chatham as ‘a great Invisible Power’ that left no minister in the House of Commons. It is scarcely too much to say that to the active opposition of Burke during this session is to be attributed the distinct position assumed by the Rockingham whigs. Yet while he was firmly attached to his party, and unsparingly mocked at the disorganisation which prevailed in Grafton's ministry, Goldsmith was mistaken, as far as this period of his career at least is concerned, in saying in 1773 that Burke by leaving literature for politics gave ‘to party what was meant for mankind’ (Retaliation). For though he held loyalty to his party to be the duty of every man ‘who believes in his own politics’ (‘Present Discontents,' Works, iii. 170), he showed his independence by alone refusing to vote for Dowdeswell’s roposition for reducing the land-tax (Walpole, George III, ii. 421). In May 1767, when the house lightly adopted Townshend's plan for laying duties on the American trade, Burke declared that the ministry would find out their mistake. ‘You will never,' he said, 'see a shilling from America’ (Cavendish, Rep. i. 39). By the acknowledgment of his opponents he was ‘the readiest man on all points, perhaps, in the house,’ and his pre-eminence shocked and disgusted them. It was grievous to them to find themselves helpless before the attacks of this ‘Irish adventurer,' a man whom the would jealously exclude from the high offices of state. To the magnates of his own party Burke now made himself indispensable. He wrote ‘protests’ for them, and during the vacation discussed affairs at their country houses with an energy they could scarcely understand, but of which Rockingham and the dukes of Newcastle and Richmond were glad to avail themselves (Works, i. 73, 75). On the meeting of parliament on 24 Nov. he spoke on the address with great applause, pointed out the futility of the king's speech, and taunting the ministers with having no policy for the relief of the poor during the prevailing scarcity, though the distress was so severe that riot would follow the despair of the people, and ‘the law, if enforced upon them, must be by the bloody assistance of a military hand’ (Parl. Hist. xvi. 386).

On 1 May 1768 Burke wrote to Shackleton: ‘I have made a push with all I could collect of my own, and the aid of my friends, to cast a little root in this country. I have purchased a house, with an estate of about six hundred acres of land, in Buckinghamshire, twenty-four miles from London, where I now am’ (Works, i. 77). This estate was Gregories, situated about a mile from Beaconsfield, and after 1770 generally called by its owner after that town. As Burke at the time of his marriage was certainly a poor man, this purchase is strange, and has given rise to much controversy. The purchase-money was about 20,600l., of which 14,000l. was raised by two mortgages, which remained on the property until the reversion was sold by Burke's widow Sir J. Napier, Burke, a Lecture, p. 61). How the remainder was raised, how Burke could have ventured tn so large a purchase, and how he expected to meet the expenses of living in such a place, have neverbeen satisfactorily explained. The explanation must he sought in the share he had in the profits derived from the speculations of certain members of his family. It has been satisfactorily proved that his brother Richard and his kinsman William, with whom he lived on terms of the closest intimacy, gambled desperately in stocks, and that Lord Verney was engaged with them (Dilke). All three were ruined by the fall of East India stock in June and July 1769. In the June of that year Burke was one of the proprietors of the East India Company, though in a letter written in 1772 he denied that he ever had 'any concern in the funds of the company (Works, i. 199). It is also certain that the same month to Garrick asking for the loan of 1,000l., and that from that time onwards he was always in the greatest need of money, on one occassion joining with W. Burke in a bond for so small a sum as 250l. For some time, however, the speculations of the Burkes prospered. In 1765 Burke was in a position to bear a large share in the expense of sending Barry to Italy. Writing to Barry in October 1766, W. Burke says; 'Whether Ned is employed or not is no matter of anxiety to us; 'and again in December, when expecting the downfall of the Rockingbam ministry: 'It suits my honour to be out of place, and so will our friend Mr. E. B. ; but our affairs are so weil arranged that, thank God, we have not a temptation to swerve from the straightest path of perfect honour' (Barry, Works, i. 24, 61, 77). Among the three Burkes there was the strictest alliance. Burke's house in London, and afterwards in the country, was the home of his brother and cousin, and at this time at least they all had one purse. In 1768 then, Burke, believing that the success that had hitherto attended the speculations of his brother and cousin would continue, was emboldened to buy Gregories, and to involve himself in the expenses which such a purchase naturally entailed. When in 1769 the crash came, it was too late to go back. As regards tho 6,000l. which complete the purchase, it has been assumed that this sum was lent by Lord Buckingham (Morley, Life, 35). On the other hand we find that in 1783 a suit in chancery was brought against Burke by Lord Verney to recover a sum of 6,000l., stated to have been lent to him in the spring of 1769 on the solicitation of his cousin William. In his answer Burke admitted borrowing 6,000l. in that year, but denied that he had it of Lord Verney, declaring also that the only relationship between him and William, as far as his knowledge went, consisted in the fact that their fathers called each other cousins. The pleadings in this suit make it probable that this 6,000l. was some sum that had accrued to Burke from the stockjobbing transactions of his brother and cousin ; that, not being personally liable for their dafalcations, he saved this sum out of the fire ; and that Lord Verney afterwards tried prove that he bad a right to it. The share Burke almost certainly had in the profit arising from the speculations of his kinsmen is perhaps the foundation of the amazing assertion that 'he received about 20,000l, from 'his family' (Prior). There is no direct evidence that he took part in these transactions, and there is no reason for supposing that they exercised any influence on his political conduct (on this matter see Dilke, Papers of a Critic, ii. 331-84). He certainly shared the good fortune of his kinsmen, and, though not ruined to the same extent that they were, shared also the consequences of their failure. From 1769 onwards he was never free from difficulties. He received help from some generous friends, such as Lord Rockingham, Garrick, and others. He was not a man to retrieve his losses by carefulness. He lived at Beaconfield not extravagantly, but not frugally, driving four black horses, and spending 2,500l. a year, exclusive of his expenses in London during the sessions of parliament (Stanhope, Life of Pitt, ii. 250). His letters to the great agriculturist, Arthur Young, show that when he was in the country be was an eager tanner, intent on cultivating his land in the most scientific and profitable fashion (Works, i. 123-32).

On the opening of the session of 1768-6, Burke exposed the dangers into which the carelessness of Grafton's ministry was leading the country as regards both its American policy and its acquiescence in the annexation of Corsica by France, a power which he always regarded with suspicion. In reply to Grenville's manifesto against the Rochingham party, he published early in 1769 his 'Observations on a late Publication on the Present State of the Nation.’ In this pamphlet, after a brilliant criticism of Grenville’s economic statements, he considers the proposed remedies; he rejects the idea of an enlar d franchise, on the ground ‘that it would be more in the spirit of our constitution by lessening the number to add to the weight and independeniy of our voters,’ and sets aside the propos for American representation as ‘contrary to nature' (Works, iii. 70). He always looked on any meddling with the constitution as a dangerous matter, and this reverence for the established order sometimes led him to speak and write as though its preservation were of greater moment than the liberty which was the very reason of its existence, while by his favourite metaphor of ‘equipoise ’ he represented the risk attending the slightest change (‘Present Discontents,’ Works, iii. 164; Morley, E B., a Study, 114). All his political wisdom was called for by the events of 1769. He strove vigorously, but unsuccessfully, against the action of the House of Commons with reference to Wi1kes, condemning Lord Weymouth’s letter to the Surrey magistrates, and pointing out that soldiers were not lawful executors of justice. In this debate and often during the session he was answered by the unblushing Rigby (Cavendish, Rep. i. 139-49). His arguments on this subject were received with clamour. On 15 April, when insisting that the house was engaging in a contest with the whole body of the freeholders of England by declaring Colonel Luttrell M.P. for Middlesex, he was interrupted ‘by a great noise in the house,' some member meanwhile whispering with the speaker. His temper was roused. ‘I will he heard,’ he exclaimed? ‘I will throw open the doors’ (the lobby and even the passages of the house were crowded) ‘and tell tell the people of England that when a man is addressing the chair in their behalf the attention of the speaker is engaged’ (ib. 378). During this session he opposed the bargain by which the government mulcted the East India Company of 400,000l. a year, and condemned the unconstitutional demand made upon the house for the payment of a debt on the civil list before the production of accounts. He also moved foran inquiry into the conduct of the vernment with reference to the riot in St. George’s Fields, the fruit of Weymouth’s ‘bloody scroll,’ denying that ‘the military power might be employed to any constitutional purpose whatever’ (ib. 310). The summer gdurke spent at Beaconsfield, where, as he writes to Rockingham, the rain put him to much expense in getting in his clover and deluged his hay (Works, i. 82). His farming anxieties, however, did not long interrupt a new work he had on hand (ib. 91). This was his ‘Thoughts on the Present Discontents,' which was published on 23 April 1770. To this pamphlet is to be attributed the regeneration of the whigs by the revival of the principles of 1688, which had been wellnigh forgotten by the intrigues of the Bedford faction (Morley, EB., a Study, 15). Burke defended the popular discontent, declaring that ‘in all dgputes between the people and their rulers the presumption was at least upon a par in favour of the people’ (Works, iii. 114). The fault lay with the administration; the power of the crown had revived under the name of influence, and the intrigues of the court cabal were taking the place of the interests of the people. Examining the popular remedies, he rejected the proposal for shortened parliaments, for frequent elections would, he believed, only increase the influence of the administration, nor would he shut all place-rnen out of parliament, for he held that corruption would thus be increased by concealment. The true remedies were to give weight to the opinion of the people by doing away with the secrecy of parliamentary proceedings, and to substitute loyal adherence to party for the influence of the court. The indignation with which the whig oligarchs received this pamphlet is depicted in the sneers of Walpole (George III, iv. 129-47). Chatham, who was aggrieved by the position it took with reference to reform, wrote to Rockingham that it would do great harm to the party, probably not expecting that Rockingham would show the letter to Burke. He did so, however, and twenty years after Burke was still indignant at it, though he warmly acknowledged ‘the great splendid side’ of his opponent’s character (Albemarle, Memoirs of Rockingham, ii. 195). The ang? of the advanced party was expressed by Mrs. Catherine Macaulay in a violent answer, entitled ‘Thoughts on the Causes of the Present Discontent.'

Burke soon carried the principles of his pamphlet into action by struggling for the political rights of the people. He is said, though on very doubtful authority (Anecd. of Junius, p. 15), to have defended the character of Johnson when attacked on account of the publication of the ‘False Alarm’ (there seems to be a confusion between Burke and Fitzherbert, Cav. Rep. i. 516). In the spring of the next year he upheld a motion on the law of libel, with the view of protecting the right of private persons to criticise the actions of their rulers, and took a prominent part in opposing the proceedings taken by the house against certain printers for publishing debates. Referring to the twenty-three divisions by which, on 14 March 1771, he and his friends hindered the business of the house, during the debate on the prohibition of printed reports, he declared that he took shame to himself that he never resorted to this expedient before as a means of hindering such measures. ‘Posterity,’ he said, ‘would bless the pertinaciousness of that day ’ (ib. ii. 395). The freedom of the press and the publication of parliamentary proceedings were its results, Burke strongly urged the removal of restrictions on the exportation of oorn, pointing out in committee, on 28 Feb. 1770, the identity of the interests of the consumer and the grower (ib. i. 476); and again when, on 15 April 1772, a bill was before the house to regulate the corn trade, he opposed the discontinuance of the bounty on exportation (Parl. Hist. xvii. 480). In the same session of 1772 he supported a bill to protect the holders of land against the dormant claims of the church (Works, vi. 155). He was constantly assailed by anonymous pamphleteers, whose virulence was increased by the belief that he was the author of the ‘Letters of Junius,' a report which he expressly denied, and for which there was not the slightest ground (ib. i. 133-8). It was nevertheless widely spread, and was encouraged by the hints of Francis (Memoirs of Sir Philip Francis, i. 220, 243; Grenville Papers, iv. 381, 391). During the summer of 1770 his wife’s health caused him some uneasiness; she regained her strength the next year, and Burke writes cheerfully to Shackleton (July 1771); his kinsman William was living with him, his brother Richard was expected from the West Indies, and his son was doing well at Westminster. Burke’s home life was happy; he entered into all work with energy, and discussed the principles of deep ploughing as eagerly as the fate of empires.

In 1772 Burke opposed a (petition from certain clergy to be relieved from subscription to the articles, arguing that the church as a voluntary society had a right to dictate her own terms of membership, and exposing the absurdity of the proposal to substitute a compulsory subscription to the Scriptures (ib. vi. 80-90). He gave his cordial support in 1773 to the bill for the relief of protestant dissenters from the test provided by the Act of Toleration. His love of religious freedom was, however, subordinate to his dislike of rationalistic criticism. ‘Infide1s,’ he said, ‘are outlaws of the constitution, not of this country, but of the human race. They are never, never to be supported, never to be tolerated‘ (Hn. vi. 100). The special cause of this vehemence was a visit he paid to Paris in February 1773, whither he went after leaving his son Richard at Auxerre to acquire French. On this visit he saw the Dauphiness at Versailles, that ‘delightful vision’ which some sixteen or seventeen years after he described in memorable words (ib. iv. 212). He supped often with Mme. du Deffand, who Wrote to Walpole that he spoke French with great difficulty but was most agreeable. At her house he met the Comte de Broglio, and at the house of the Duchesse de Luxembourg he heard the ‘ Barmécides ’ of La Harpe. In the salon of Mdlle. de l’Espinasse he found himself in the society of the Encyclopaedists, and had an insight into French morals and philosophy (Lettres de Mme. la Marquise du Deffand, ii. 377-93; Morley, Life, 67). He came back in March strengthened in his conservative principles. About this time his brother Richard, who had been ruined in 1769, appears as a speculator in land in St. Vincent. His title was disputed by government, and Burke was suspected of having been concerned in his gambling transactions (Dilke; H. Walpole to Mason, 23 March 1774, Letters, vi. 68). In the autumn of 1771 Burke had been appointed agent to the province of New York, with a salary of 500l. a year (Bancroft, Hist. of the U. States, v. 215). A more lucrative offer was made to him the next year. The East India Company was in difficulties, and dreaded the seizure of its territory by government. The directors wished to send Burke, at the head ofa supervisorship of three, to reform their administration. Burke took counsel with the Duke of Richmond, and refused the tempting offer for the sake of his party. That party was soon to receive an important addition. At least as early as 1766 Charles James Fox, then about seventeen, was intimate with Burke, admired his talents, and probabl before long introduced him to Lord Holland (Correspondence of C. J. Fox, i. 26, 69). In February 1772 Fox left North's administration, and he and Burke united in opposing the Royal Marriage Act. The breach was patche up, but in 1774 Fox finally went into opposition and thus became an ally of Burke, whom he always looked up to as his master in politics. For the next eight years the two friends joined in violent opposition to North’s administration. They led very different lives, for Burke neither drank nor played. and when, after a hard morning’s work, he used to call for Fox on his way to the house, he would find him fresh and ready for work, for his day had then only just begun.

In the spring of 1774 Burke urged the repeal of the tea duty in a speech afterwards published (‘On American taxation,’ Works, iii, 176), and vigorously opposed the penal bills for closing the port of Boston and annulling the Massachusetts charter. The dissolution of parliament in September caused him some anxiety, for Lord Verncy’s affairs compelled him to have candidates stand for Wendover who could bear the charges of the borough (ib. i. 237). Rockingham, however, found him a scat at Malton. On his way to the election there he was robbed of 10l. by a highwayrnan (ib. 246). While he was at dinner on the day of his election, 11 Oct., a deputation from Bristol arrived at Malton and informed him that he had been nominated for that city. He set off at once, and, arriving at Bristol in the afternoon of the 13th, the sixth day of the poll, drove straight to the mayor’s house, and, after a few minutes’ rest, addressed the electors in the Guildhall (ib. iii. 227). At the close of the poll, 3 Nov., he was elected by a maiority of 251. His colleague, Mr. Cruger, having declared himself willing to obey the instructions of his constituents, Burke explained the constitutional position of a parliamentary representative: ‘He owes you,’ he said, ‘not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays instead of serving you if he sacrifices it to your opinion’ (ib. 236). His success afforded him great pleasure, and in a cheerful letter, dated 19 Nov., he describes how on his way home he visited his son Richard, then at Christ Church, Oxford, and ‘drank a glass of wine with him and his young friends (ib. 249). On 6 March 1775 he made an indignant protest against restraining the trade of the American colonies (Parl. Hist. xviii. 389), and on the 22nd brought forward his thirteen resolutions for conciliation 478 ; Works, iii. 241). He spoke for three hours. With the question of the right of taxation he would have nothing to do. ‘It is not,’ he said, ‘what a lawyer tells me I may do, but what humanity, reason, and justice tell me ought to do.‘ he resolutions were negatived by 270 to 78. Burke's health seems to have suffered from his unavailing exertions. On 15 May, in presenting a representation from the Assembly of New York, his American constituency, he said that he was too ill to makea long speech, and writing to Rockingham on 4 Aug. he spoke of an illness from which he had just recovered. ‘My head and heart,’ he said, ‘are full of anxious thoughts? Yet in spite of toil and sickness his spirits were elastic. Boswell, in a letter written at this time, thinks that ‘he must he one of the few men that may hope for continual happiness in this life, he has so much knowledge, so much animation, and the consciousness of so much fame' (Letters to Temple, 212). He was the centre of attraction at one or two London salon, and especially at Mrs. Vèsy's gatherings. There, and in other drawing-rooms where he was at ease, he would take a book, if he did not care for the company, and read aloud, sometimes choosing French poetry, which he read as though the words were to sound as in English (Memoirs of Dr. Burney, ii. 267, iii. 170.)

On the occasion of presenting a petition setting forth the in'u arisin to the Wiltshire clothiers from the Ameiican troubles, Burke made another attempt to bring the government to a peace and the rejection of his motion by 210 to 105 was considered a triumph by the minority (Parl. Hist. xviii. 963). In Novemher of the next year (1776) he seconded a motion for the revision of all acts aggrieving the colonies. On the rejection of this motion he, in common with the party to which he belonged, withdrew himself from parliament on a questions relating to America (ib. 1434; Ann. Reg. 1777, 48). This partial secession called forth his ‘Letter to the Sheriffs of Bristol,’ which contains a defence of his opposition to the government measures. Although his attention was at this time chiefly directed to our colonial troubles, he joined with Sir W. Meredith in fighting against the brutality of the law and general manners at home. He brought in a bill to hinder wrecking, and in 1779 made an earnest protest against the punishment of the pillory. On his return to full parliamentary attendance, he made a motion, 6 Feb. 1778, against the employment of Indians in the war with America, supporting it with a speech of three hours and a half, which excited much applause that the ministers, who as usual on these occasions had cleared the house of strangers, were congratulated on their prudence, for it was said that had the public heard Burke’s speech their lives would have been in danger (ib 1778; and see above). The government of Lord North, indeed, gave ample cause for the indignation Burke was not slow to express. A few days after this speech on the Indian question Lord Mulgrave, in a debate on the navy estimates, acknowledged that not a shilling had been laid out on the purposes for which the last vote had been made, and treated the apropriation as a mere matter of form. At this open defiance of the principles of the constitution Burke's anger blaze out. Snatching ‘the line gilt book of estimates’ from the table, he flung it at the treasury bench, and, though the volume hit the candle and nearly hit Welbore Ellis, the treasumer of the navy, on the shins, no one seems to have dared to complain of this display of righteous wrath (Parl. Hist. xix. 730). On the motion for the trial of Sir Hugh Palliser for his conduct in the action off Ushant, Burke warmly upheld the cause of Admiral Keppel (ib. xx. 54-71), and in January 1779, in company with Rockingham and other great men of his party, went down to Portsmouth to be present at his trial by court-martial. Some parts of Keppel's defence are in his handwriting, and he shared in the joy felt at the verdict, which at once absolved the admiral and abased the ministers.

Burke's resistance to any change in the form of the constitution he venerated was accompanied by a desire to amend its working. He saw that the constitution was paralysed by corruption, and, with the idea of securing political health by enforcing economic purity, he laid before the house, 1 Feb. 1780, a plan for the better security of the independance of parliament and the economical reformation of the civil and other etablishments (Works, iii. 343). In a large and yet conservative spirit he sought to sweep away merely useless places and to destroy the accretions of jobbery which had grown round the court and had become at once a burden to the taxpayer and the food of ministerial corruption. He hoped to invigorate the constitution by sweeping away the useless places, the lavish pensions, and the ridiculous extravagance which enabled the court to keep a considerable number of members of parliament either in its immediate pay or hound to it by the expectation of future profit. North managed to defeat the bill by taking it in detail (Morley, E. B., a Study, 166).

Burke was too good an Irishman to be unmindful of the needs of Ireland. He saw clearly that the only means of bettering her condition was the admission of his countrymen to the privileges enjoyed by Englishmen, by the removal of trade restrictions, and by the relief of the catholics. Holding these views he naturally opposed the measure advocated in 1773 for imposing a tax on all absentee landlords, and in his ‘Letter to Sir C. Bingham ’ pointed out that, among other evils, such a, tax ‘would go directly against the happy communion of the privileges’ of the two kingdoms (Works, v. 502). In 1778 he joined Lord Nugent in obtaining some relief from the restrictions on trade, and finally, in 1779, succeeded in forcing Lord North to recognise the necessity of giving up the English monopolies (Parl. Hist. xx. 137, 1132, 1272). He also supported the slight relaxations of the penal laws made in 1778. On l8 May in the following year he advocated the relief of the Scotc catholics. Accordingly, on the outbreak of the Lord George Gordon riots in June 1780, his friends tried to persuade him to go out of town. He resolved, however, that the mob ‘should see that he was not to be forced nor intimidated from the straight line of what was right,’ and walked through the streets as usual, letting the people know who he was. He met with no annoyance. His house in Charles Street was occupied by a guard of soldiers, and he and his wife spent the week under the roof of General Burgoyne (Works, i. 432-5). Burke’s advocacy of the commercial rights of Ireland deeply offended the Bristol merchants, and his religious toleration increased their discontent (ib. 442). Parliament having been dissolved on 1 Sept. 1780, he Went down to Bristol and explained his views to his constituents. After a canvass of two days he found his election hopeless, and declined the poll (ib. iii. 407-47; Gent. Mag. l. 618). He stood by Fox during the Westminster election, and then went down to Beaconsfield, ‘wearied with the business, the company, the joy, and the debauch.' Lord Rockingham having provided him with a seat for his borough of Malton, Burke, in February 1781, again brought forward his bill for economical reform, but was defeated on the second reading by 233 to 190, On this occasion he was delighted at the speech made in support of his motion by William Pitt, and declared that he‘ was not a chip of the old block but the old block itself’ (Sir N. Wraxall, Hist. Mem. ii. 342). On the opening of the November session of 1781 Burke commented severely on the folly of the king's speech, which, in spite of the surrender of Cornwallis, still dwelt on the maintenance of our rights in America. Right, he said, signified nothing without might, and he compared the ministry to a man who would shear a wolf (Parl. Hist. xxii. 717). During the spring of the next year he and Fox made a series of attacks on the conduct of the war, which at last forced North to retire.

On the accession of the Rockingham whigs to office Burke was not offered a seat in the cabinet, and the party thus threw away a ‘ real guarantee ’ against the preponderance of the Shelburne section in the administration (Russell, Life and Times C. J. Fox, i. 284). The constant exclusion of Burke from cabinet office was to some extent due to the fact that he was a difficult man to work with. Fox once said that he was ‘a most impracticable person, a most unmanageable colleague; that he never would support any measure, however convinced he might be in his heart of its utility, if it had been prepared by another’ (S. Rogers, Table-talk, 81).' This, however, was said after the rupture of their long alliance, and, though Burke evidently lost his self-control at a later period, is only partially true of him in 1782. The most effectual cause of his exclusion was the narrow jealousy with which the whig oligarchs regarded the rise of the Irish adventurer. Burke was a pointed paymaster of the forces. He actively forwarded the concession of self-government made to Ireland by the repeal of 6 Geo. I and other acts. ‘Her cause,' he said on 16 April, ‘was nearest to his heart, and nothing gave him so much satisfaction when he was first honoured with a seat in that house, as that it might be in his power to be of service to the country that gave him birth’ (Parl. Hist, xxiii, 33). Burke's proposals for economical reform formed the chief subject of discussion in the cabinet. An attempt was made to place the matter in the hands of the crown. Burke drew up reasons to be urged by Rockingham on the king, showing that the reform ought to proceed from parliament (Works, i, 492). The king yielded. A compromise was effected; and though Burke was forced to give up a large part of his scheme, he was able to carry some substantial reforms affecting public offices. Among these was the regulation of the office he himself held. It had been the custom for the paymaster to keep the balances of public money in his own hands until the audit. Burke fixed the salary at 4,000l. a year, and paid in his balances to the Bank of England, thus increasing the income of the country by a large sum. He made his son Richard his deputy, with a salary of 500l. At the same time he was given to understand that ‘something considerable’ would be secured for his wife and son (ib. i. 500). By the death of Rockingham on 1 July Burke lost not only a true friend, but a wise leader who directed and controlled his fervour (Life of Fox, i. 319). In his difficulties with Shelburne Fox took counsel with Burke, who, while advising him to refuse to act ‘as a clerk in Lord Shelburne’s administration,' urged him to put off his resignation until the next session (Mem. and Corresp. of C. J. Fox, i. 457), Fox, however, resigned at once, and Burke followed him out of office.

Having thus lost office before the promised provision had been made for his wife and son, Burke sought to secure for his son the reversion of the rich sinecure of the clerkship of the pells. He failed in his attempt. His conduct in this matter has been severely blamed (ib. i. 451). He had, however, been led to expect some reward; he had certainly a far stronger claim than the crowd of noble place-men and pensioners who enjoyed the wealth of the country in idleness, and, however objectionable such arrangements were, they formed the recognised mode of rewarding public services. Burke acquiesced in the extraordinary coalition between Fox and North, and on the overthrow of Shelburne’s administration in February 1783 again accepted the office of paymaster in the Portland government. On his return to office he incurred considerable censure by reinstating two clerks, Powell and Bembridge, who had been dismissed by his predecessor for fraud. Powell was believed to have been mixed up with ‘the Burkes’ in their operations in India stock (Drum), and his suicide and the conviction of Bembridge were held to be proofs of Burke’s corrupt motives. He warmly defended his conduct, and in a debate on 2 May waxed so violently angry that Sheridan pulled him down on his seat from a motive of friendship. He declared that ‘he acted upon his conscience and his judgment in protecting men he believed to the simply unfortunate’ (Parl. Hist. xxiii. 801, 902). The ministers were pledged to take measures to promote the good government of India. Burke had for man years been deeply interested in the affairs of that country. He highly disapproved of North’s Regulating Act, and as early as 1773 expressed his distrust of Hastings, the first governor-general appointed in accordance with it (Macknight, ii. 25). He served on the select committee on the affairs of the East India Company, and in 1783 drew up the ‘Ninth Report,’ ‘one of the most luminous and exhaustive of English state papers’ (Morley), on the trade of Bengal and the system pursued by Hastings, an the ‘Eleventh Report,' dealing with the question of presents. He also prepared the draft of the famous East India Bill introduced by Fox in December (Works, i. 515), and supported it by a speech which Wraxall, who was no friend of his, declared to be the finest composition pronounced in the House of Commons while he was a member of it. On 18 Dec. the ministers were dismissed. Burke had been out of spirits during the continuance of the coalition ministry. Such reminders, indeed, as the ‘Beauties of Fox, Burke, and North,’ a collection of the bitter things he and Fox had said of their-then colleague in past days, were scarcely needed to make him feel that he was out of place by the side of the minister whom he had so unmercifully assailed, and the lofty tone of the invectives he had uttered made the union seem especially unnatural. He found his influence weakened. On one occasion when he rose to speak, a number of members noisily left the house, and he resumed his seat in anger. His depression did not escape Miss Burney, who remarks upon it. Burke, who had lately made her acquaintance, greatly admired her.

He sat up all night reading ‘Evelina,' and carried ‘Cecilia’ about with him, readign it at every leisure moment until he had finished it. His last official act was to procure Dr. Burney the appointment of organist at Chelsea College (Mme. d’Arblay, Diary, ii, 271; Memoirs of Dr. Burney, ii. 376; Macknight, iii. 58–60).

Burke’s depression seems to have continued during the early months of 1784, and he took little part in politics. Having been elected lord rector of Glasgow, he visited the university in April, and was installed in his office. It is said that, on rising to deliver an address on this occasion, he for once found himself at fault, declaring that he had never before addressed so learned a body, though he afterwards made a speech which was received with much applause. The triumph of Pitt and the king, and the consciousness that public opinion was against him, led him, on the meeting of the new parliament, to move a representation to his majesty on the constitutional aspect of the late dissolution (Works, iii. 515). Two hours were occupied in reading this document; the house heard it with impatience, and negatived it without a division. He was now constantly greeted with rude interruptions when he rose to speak. ‘I could teach a pack of hounds,’ he said on one such occasion, ‘to yelp with greater melody and more comprehension.' The anonymous attacks upon his character,‘the hunt of obloquy,‘ never ceased. One charge brought against him by the ‘Public Advertiser ’ was so gross that he was forced to prosecute the printer, and obtained a verdict for 100l. damages and costs (Ann. Reg. 1784, p. 197). At Beaconsfield he found peace and happiness. There he entertained his old friends, with his own hands dispensed food and medicine to the poor, and now and then patronised a company of strolling players, and helped to replenish their wardrobe. He was a constant attendant at the parish church, and used to spend the time between morning and evening prayer in chatting with the parson.

Burke was now steadfastly set on making Hastings answer for his misdeeds. Great difficulties stood in his way; the house where Pitt was now supreme had ceased to treat him with respect, and his speech of 28 July on the ministers' India Bill, which certainly contained a passage at once vehement and ludicrous, was unfavourably received (Parl. Hist. xxiv. 1214). Pitt threw obstacles in his way, and Major Scott, the agent of Hastings, taunted him with the non-fulfilment of his threats. The opposition, however, took up the matter, and on 28 Feb. 1785 Fox moved for papers relating to the debts of the nabob of Arcot, On this occasion Burke made a speech full of eloquence and of surprising knowledge of this intricate subject (Works, iv. 1). Even while fully engaged in preparing for his great attack, he was alive to wrong in every shape, and effectually interfered to prevent the establishment of a penal settlement in the unhealthy district of the Gambia river (Parl. Hist. xxv. 391, 431). When, in July, Pitt brought forward his resolutions on Irish commerce, by which Ireland would have attained perfect equality in trade, subject to a contribution to certain imperial objects, Burke, contrary, as it seemed, to his former policy, oppose the minister. His conduct has been blamed as factious (Morley, E. B., a Study, 188). Allowance should, however, be made for his susceptibility on all matters affecting his native country, quickened as it was in this case by his remembrance of American disaster, for he based his opposition on the ground that the resolutions were imposing a ‘tribute’ on Ireland, and indicated a policy such as had led to the contest with America (Parl. Hist. xxv. 647). His re-election at Glasgow was the cause of another visit to Scotland in the autumn of this year, and of a very pleasant tour over a considerable part of that country (Works, i. 522). In the course of this tour, on which he was accompanied by his son and his friend Windham, he visited Minto, the seat of Sir G. Elliot, where he astonished Dr. Somerville of Jedburgh, who gives an interesting account of his conversations with him, by the richness of his language and the universality of his knowledge (T. Somerville, Own Life and Times, 220–3). The early part of 1786 was taken up with the preliminaries of the attack on Hastings, in which Burke found an eager ally in Philip Francis, with motions for papers and the like. On 1 June he moved the Rohilla charge, and, though ably supported by Fox, was defeated by 119 to 67. Pitt, however, unexpectedly agreed to an article of the impeachment moved by Fox, and Burke thus gained his object. Other charges were moved by Sheridan, Windham, and Francis, but Burke inspired every speaker, and took an active part in the debates. At length, 10 May 1787, attended by a majority of the commons, he appeared at the bar of the House of Peers, and solemnly impeached Hastings of high crimes and misdemeanours (Parl. Hist. xxvi. 1149).

Burke still had much opposition to contend with, and the refusal of house to appoint Francis a manager of the impeachment, ‘a blow he was not prepared to meet,’ much discouraged him (Memoirs of Sir Philip Francis, ii. 243). On 13 Feb. 1788, the first, day of the trial, Westminster Hall presented the famous scene described by Lord Macaulay (Essay on Warren Hastings). Burke, as head of the managers for the impeachmcnt, solemnly entered the hall. He walked alone, holding a scroll in his hand, his brow ‘knit with deep labouring thought’ (Mme. d'Arblay, Diary, iv. 59). On 15 Feb. he began his opening speech (Works, vii. 279), which formed an introduction to the whole body of charges. He spoke during four sittings. On the evening of the l7th, after describing the cruelties practised by Debi Sing on the natives of Bengal, he was overpowered by indignation, and seized with an attack which made it necessary for him to break off his speech. On the next day he concluded it with a stately peroration. The effects of his exertion do not seem to have passed away for some time, for on 1 May he wrote to the speaker excusing his absence from the house on the plea of illness and the necessity of a short rest (ib. i. 541). On 6 June, on a motion relating to the expenses of the trial, he eloquently complimented Sheridan on his speech on the princesses of Oude. In the course of this summer Burke was successful in a lawsuit with a neighbour, Mr. Waller of Hall Barn, who claimed some manorial rights over his estate. His constant need of money is proved by his grateful acceptance in July of a gift of 1,000l. from his friend Dr. Brocklesby (ib. 544).

When, in November 1788, Fox was called home from the continent by the news of the king’s insanity, Burke expected to be summoned by his friend, who was now generally looked upon by his party as the future minister (ib. i. 545). Fox, however, did not send for him, and though Burke joined him in upholding the right of the Prince of Wales to the regency, and in opposing Pitt’s restrictions, he was treated with neglect. Some difficulty arose as to finding a chancellor of the exchequer for the cabinet it was proposed to form in case the party succeeded in turning Pitt out of office, but Burke’s name was not approved. At a private meeting of some of the leaders of the Portland party, held 9 Jan. 1789, it was determine to again appoint him to the insignificant post of paymaster, and to secure him a pension of 2,000l., with the reversion of half to his son and half to Mrs. Burke, and to give office to his brother Richard. The Duke of Portland, Windham, and Elliot, who were his sincere friends, believed that this was ‘acting in a manner equal to Burke's merits’ (Life and Letters of Sir G. Elliot, 261-3). Several special difficulties stood in the way of his nomination to cabinet office at this crisis. With the Prince of Wales and his set he had nothing in common save the politics of the party. ‘I know no more,‘ he said, in December 1788, ‘of Carlton House than I do of Buckingham House.’ Always irritable, even with friends so true as Windham, he seems when vexed by opposition to have lost all control over himself (Windham, Diary, 112, 167). His vehemence in debate increased with neglect. On 6 Feb., for example, he declared the conduct of the ministers ‘verging to treasons, for which the justice of their country would, he trusted, one day overtake them and bring them to trial’ (Parl. Hist. xxvii. 1171). He was accused, not altogether unjustly, of outraging propriety in his speeches on the king's condition (Sir N. Wraxall, Posth. Mem. iii. 323, 346). His enemies, and indeed ‘half the kingdom, considered him little better than an ingenious madman’ (Windham, 213). These causes, combined with his poverty, the scandalous stories of his enemies, the constantly repeated accusation that he was ‘Junius,’ and above all the exclusiveness of the whig aristocrats, hindered the due recognition of his services and talents. The dignified letter he composed for the prince accepting the regency is a sufficient proof that when unchafed by the insults of Pitt’s rank and file, unvexed by neglect, and unexcited by debate, his wisdom and judgment were not less than in earlier years. He longed to ‘retire’ for good and all, but the Indian business ‘kept him bound' (Works, i. 549). He resumed this business in April. Public interest in the trial had now declined. Burke had become unpopular, and the friends of Hastings were strong in the house. A violent expression used by Burke respecting the death of Nuncomar was made the occasion of a vote of censure, passed 4 May. Contrary to Fox's wish, Burke continued the trial the next day, and the difference of opinion occasioned a slight soreness between them (Corresp. of C. J. Fox, ii. 355). Burke has been accused ‘of surrendering himself at this period of his career to a systematic factiousness that fell little short of being downright unscrupulous (Morley, E. B. a Study, 27) He certainly worked hard for his party, for he had not as yet seen reason to differ from its general policy, and in such circumstances he ever held loyalty to his party to be incumbent on a statesman. He wrote, it is true, to Fox, on 9 Sept. 1789, suggesting that he should conciliate Dr. Priestley and his followers, in view of a general election (Corresp. of C. J. Fox, ii. 360). There is, however, nothing in this letter contrary to the principles he held in 1773. He disliked and distrusted the unitarians then, and he did so now, but that was no reason why his party should lose their support for law; of a piece of ordinary civility such as he recommended. As early as 1780 Burke had drawn up regulations to mitigate the evils of the slave trade, and of thc employment of slaves, in the form of a letter to Dundas (published in 1792). He therefore hailed with delight the attack made on the trade by Wilberforce. On 9 May 1788, in the debate on Pitt’s motion for inquiry, he declared that he wished for its total abolition, and on 12 May 1789 warmly praised the speech with which Wilberforce introduced his resolutions (Parl. Hist. xxvii. 502, xxviii. 69, 96; Life of Wilberforce, i. 171).

Having been requested by a friend, M. Dupont, to send him his opinion of the revolutionary movements in France, Burke wrote to him in October, though the letter was not sent until some weeks after. In the meantime the open expression of sympathy with these movements, and especially the proceedings of the Revolutionary Society on 4 Nov., stirred him to write his ‘Reflections on the Revolution’ as a warning to its English admirers. Loving ‘liberty only in the guise of order,’ he saw in the events of 6 Oct. an impending attack on the order which through all his life he had so deeply reverenced. In a debate on the army estimates, 9 Feb. 1790, he spoke strongly against the French democracy. Fox, who saw in the taking of the Bastille the greatest and the best event that ever happened in the world, made him a soothing answer. Sheridan sharply opposed his views, and Burke at once declared himself separated from him in politics. The neglect of Burke by the Carlton House faction must, to some extent at least, have been due to Sheridan's jealousy, and his speech on this occasion was evidiently intended to provoke Burke’s wrath (Parl. Hist. xxviii. 370). On 2 March Burke opposed Fox's bill for the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts. His fear of the spread of revolutionary opinions in England made him untrue to the policy of toleration he had so long upheld. ‘It was not a time,' he said, ‘to weaken the safeguards of the established church.’ Fox declared that Burke’s speech filled him with grief and shame. The bill was lost (ib. 387). In the course of this year Burke was gratified by the appointment of his son, now a barrister, as legal adviser of the Irish Catholic Committee. Meanwhile the ‘Reflections’ was slowly written and rewritten. Some proofs were sent to Francis in February. He returned them with some strong expressions of disapproval, mocking at the celebrated passage about the queen as ‘pure foppery.’ Burke, in answer, declared that when he wrote it the tears ‘wetted his paper’ (Works, i. 574). At last, after a year’s labour, the ‘Reflections' was issued on 1 Nov. 1790. Before a year had passed eleven editions of it were called for. The king was delighted; it was, he said, ‘a good book, a very good book ; every gentleman ought to read it.” The Oxford graduates presented their congratulations through Windham; it was proposed to grant him the degree of D.C.L., but the motion was defeated. This annoyed him greatly, and when, in 1793, an honorary degree was offered him, he refused it on the ground that his name had been rejected previously. From Dublin he received the LL.D. degree. The effect of the ‘Reflections’ was extraordinary. It created a reaction against the revolution; it divided Englishmen into two parties and did much to ruin the whigs, and to produce a new political combination. Chief among the many answers it called forth in England is the ‘Vindicæ' Gallicæ’ of James Mackintosh. In a different strain, but with not less effect, it had already been met by Paine's ‘Rights of Man.' One sentence in the ‘Reflections,' representing learning as ‘trodden down under the hoofs of a swinish multitude’ (ib. iv. 215), drew forth a crowd of bitter retorts; it was explained as intended to refer to Bailly. Abroad the ‘Reflections' created no less stir than at home, and Burke received the compliments of different foreign sovereigns. His political foresight is exhibited by his prophecy of the time when, all restraints that mitigate despotism being removed, France would fella prey to arbitrary ppwer. Nevertheless, in site of these and other philosophical remarks, the book contains the pleadings of an advocate rather than the reflections of a philosopher. It exhibits ignorance of the character of the French oonstitution before the revolution; it fails to recognise the social causes of the movement, and, dwelling on the sufferings of the few, it ignores the deliverance of the many.

In the parliament which met in November 1790 Burke was again returned for Malton. As the friends of Hastings hoped that the dissolution would be hcl to are put an end to the impeachment, Burke moved for a committee to consider the state of the trial. Pitt and Fox alike joined with him in advocating the constitutional principle, which was affirmed after three days' debate, that an impeachment is not abated by a dissolution of parliament. Although Burke and Fox still met on friendly terms, it was evident that the strong views each held on the subject of the revolution must before long formally break their alliance. The growing alienation of Burke from Fox and the party for which he had so lorig worked caused him pain and anxiety (Elliot, i. 364-70), and it was at this time probably that he said to Addington, ‘I am not well, Speaker; I eat too much, I drink too much, and I sleep too little ’ (Pellew, Life of Sidmouth, i. 85). Early in 1791 Burke published his ‘Letter to a Member of the National Assembly’ (Works, iv. 359). In a debate in April, Fox, provoked by this renewed attack, uttered a warm panegyric on the new French constitution. Burke rose to reply in visible emotion, but was forced to give way to the division (Parl. Hist. xxix. 249). Every effort was used to persuade Burke to let the matter pass, but ‘knowing the authority of his friend's name; he believed it necessary to bring his panegyric to trial (Ann. Reg. 1791, 115). The Quebec Bill would, he knew, give him an opportunity, und he acquainted some members of the administration with his intention. On 21 April Fox visited him and begged him to defer the final rupture, but it was too late. They walked down to the house together. In the course of a speech on the postponement of the bill, Fox, ‘meeting what he could not avoid’ to some extent, challenged Burke to express his decision, and Burke declared that ‘dear as was his friend the love of his country was dearer still’ (Parl. Hist. xxix. 362). On 6 May the house reassembled after the holidays, and, the Quebec Bill being again brought forward, Burke spoke at length on the revolution. He was called to order by various members and jeered at by Fox. Baited by one and another ignoble foe, he exclaimed:

The little dogs and all—

Tray, Blanch, and sweetheart—see, they bark at me.

(Pellew, i. 85). Fox spoke plainly of the difference of opinion between them. Burke in his reply referred to the desertion of friends. ‘There is no loss of friends; Fox whispered. Yes, he answered, there was a loss of friends—he knew the price of his conduct—he had done his duty at the price of his friend—their friendship was at an end. When Fox rose, some minutes passed before he could speak for tears (Parl. Hist. xxix. 361-88). Burke’s separation from his party brought on him a storm of calumny. It was asserted that he led Fox on to speak of the revolution that he might prejudice the king against him. Burke complained of the report in a debate on ll May, and as he and Fox defended each his own conduct, the breach between them was widened (ib. 416~26). Burke stood alone, for he had cut himself ofi, for a while at least, from the part of which he had so long been the life and the instructor. He now undauntedly set himself to enlighten his friends and lead them back to the true principles of 1688. At the end of the session he went down to Margate with his wife and his niece, Miss French, who was now living with him, and finished his ‘Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs’ (Works, iv. 392). In December he brought out his ‘Thoughts on French Affairs ’ (tb, 551), a pamphlet exhibiting the revolution as no mere political change, but as concerned, like the Reformation, with doctrines and o inious which would certainly spread unless checked by a coalition of powers. While at Margate he received a visit from Calonne, who came from the refugees at Coblentz to seek his advice. He sent his son Richard to represent him at Coblentz, a step which was allowed though not authorised by the government, while the Chevalier de la Bintinnaye was sent to represent the princes at Beaconsfield (ib. i. 633). No advice, however, could help men so impracticable as the Coblentz refugees. Richard returned home and was at once engaged by the Irish catholics, who hoped through him to gain his father’s guidance. This mission called forth the letter to Sir Hercules Langrishe, written in January 1792, in which the whole question of religious toleration in Ireland is discussed. In February Burke attended the funeral of his old friend Sir Joshua Reynolds, who leit him his executor with a legacy of 2,000l., and appointed him guardian of his niece, Miss Palmer, shortly afterwards married to Lord Inchiquin. Burke immediately sent 100l. by his son to two poor women by the Blackwater, one of them by birth a Nagle and probably one of his mother's family, adding ‘God knows how little we can spare it’ (ib. ii. 91). He took little part in the debates of this session. He opposed Grey’s notice of motion on parliamentary reform. Anger at the sympathy the unitarians expressed with the revolution and fear of disturbing the established order again led him, in May 1792, to forget his tolleant principles and oppose Fox’s motion for the repeal of certain penal statutes respecting religious opinions (Parl. Hist. xxix. 1381).