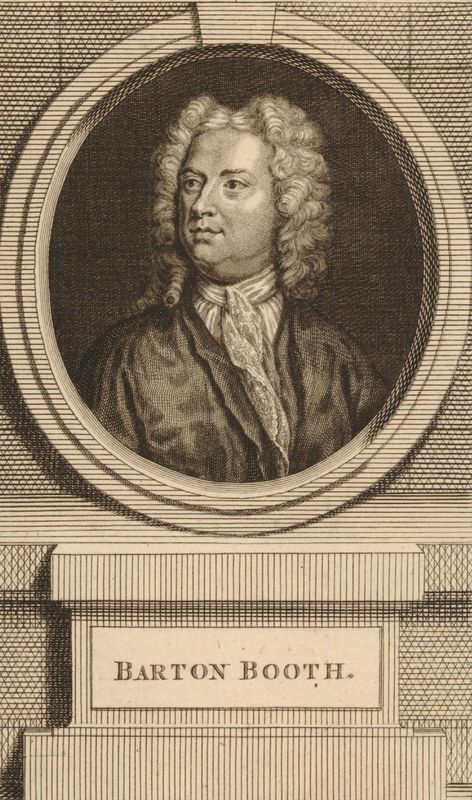

Barton Booth (1681–1733)

A General History of the Stage, by William Rufus Chetwood (1749)

Barton Booth, Esq;

This Excellent Tragedian was Son to John Booth, Esq; of the County Palatine of Lancaster, a Branch of the Warrington Family. He was born in the year 1681. in that County; but soon after his Birth his Father and Family removed to Westminster, and, at that celebrated School, the Son received his Education, under the Correction (as he call'd it) of the great Dr. Busby and Dr. Knipe. He inform'd me, the first Look he cast towards the Theatre, was from the Applause he received in performing in the Andria of Terence in Latin at Westminster-School, which perverted his Thoughts from the Pulpit, for which his Father Intended him. At Seventeen he was chose out for the University, and had Orders to prepare for his Journey; but his Inclinations prevented the Designs of his Friends.

He first apply'd to Mr. Betterton, then to Mr. Smith, Two celebrated Actors; but they decently refus'd him for Fear of the Resentement of his Family: But this did not prevent his pursuing the Point in View; therefore he resolv'd for Ireland, and safely arrived in June 1698. His first Rudiments Mr. Ashbury taught him, and his first Appearance was in the Part of Oroonoko, where he acquitted himself so well to a crouded Audience, that Mr. Ashbury rewarded him with a Present of Five Guineas, which was the more acceptable as his last Shilling was reduced to Brass (as he inform'd me). But an odd Accident fell out upon this Occasion. It being very warm Weather, in his last Scene of the Play, as he waited to go on, he inadvertently wiped his Face, that, when he enter'd, he had the Appearance of a Chimney-Sweeper (his own Words). At his Entrance, he was surpris'd at the Variety of Noises he heard in the Audience (for he knew not what he had done), that a little confounded him, till he received an extraordinary Clap of Applause, which settled his Mind. The Play was desir'd for the next Night of Acting, when an Actress fitted a Crape to his Face, with an Opening proper for the Mouth, and shap'd in Form for the Nose; but, in the first Scene, one Part of the Crape slip'd off: And Zounds! said he (he was a little apt to swear), I look'd like a Magpie! When I came off, they Lamp-black'd me for the rest of the Night[1], that I was flayed before it could be got off again.

He remained there near Two Years, and, in that Time, by Letters, reconciled himself to his Friends in England, and return'd with great Theatrical Improvement, where he gradually stept to Perfection. In 1704, he marry'd the Daughter of Sir Wm. Barkham, Bart. an antient Family in the County of Norfolk, who died without Issue in the Year 1711. Pyrrhus in the Distrest Mother plac'd him in the Seat of Tragedy, and Cato fix'd him there; and, to reward his Merit, he was join'd in the Patent, tho' great Interest was made against him by the other Patentees; who, to prvent his soliciting his Patrons at Court, then at Windsor, gave out Plays every Night, where Mr. Booth had a principal Part. Notwithstanding this Step, he had a Chariot and Six of a Nobleman's waiting for him at the End of every Play, that whipt him the Twenty Miles in three Hours, and brought him back to the Business of the Theatre the next Night. He toldl me, not one Nobleman in the Kingdom had so many Sets of Horses at Command as he had at that Time, having no less than Eight; the first Set carrying him to Hounslow from London, Ten Miles; and the next Set ready waiting with another Chariot to carry him to Windsor.

He had a vast Fund of Understanding as well as Good-nature, and a persuasive Elocution even in common Discourse, that ould even compel you to believe him against your Judgment of Things. Notwithstanding his Exuberance of Fancy, he was untainted in his Morals. In his younger Years he admir'd none of the Heathen Deities so much as Jolly Bacchus; to him he was very devout; yet, if he drank ever so deep, it never marr'd his Study, or his Stomack. But, immediately after his Marriage with Miss Santlow, whose wise Conduct, Beauty, and winning Behaviour, so wrought upon him, that Home and her Company, were his chief Happiness, he intirely contemn'd the Folly of Drinking out of Season, and from one Extreme fell, I think, into the other too suddenly; for his Appetite for Food had no Abatement. I have often known Mrs. Booth, out of extreme Tenderness to him, order the Table to be remov'd, for fear of overcharging his Stomach. His profound Learning was extraordinary, since he left School at Seventeen, took to the Stage at Eighteen, and, by his own Confession, that the Business of the Stage, joined with his Devotion to Bacchus, had taken up most of his Time since, yet I have seen him take a Classic, and render it in such elegant English, that no Translator would hardly excel. I will set down his Character from a Paper call'd the Prompter, by Aaron Hill, Esq; whose Writings will be a living Monument of his own Merit.

Mr. Booth was a Man of a strong, clear, and lively Imagination. His Conversation was lively and instructive: He had the Advantage of a finish'd Education to improve and illustrate the bountiful Gifts of Nature. Two Advantages distinguished him in the strongets Light, from the rest of the Fraternity. He had Learning to understand perfectly whatever it was his Part to speak, and Judgment toknow how far it agreed or disagreed with his Character. Hence arose a peculiar Grace, which was visible to every Spectator, tho' few were at the Pains of examining into the Cause of their Pleasure. He could soften, or slide over, with a kind of elegant Negligence, the Improprieties in a Part he acted; while, on the contrary, he would dwell with Energy upon the Beauties, as if he exerted a latent Spirit, which had been kept back for such an Occasion, that he might alarm, waken, and transport, in those Places only, where the Dignity of his own good Sense could be supported with that of his Author. A little Reflection upon this remarkable Quality, will teach us to account for that manifest Languor which has sometimes been observed in his Action; and which was generally, tho', I think, falsly, imputed to the Indolence of his Temper. For the same Reason, tho' in the customary Round of his Business he would condedscen to som Parts in Comedy, he seldom appear'd in any of them with much Advantage to his Character. The Passions which he found in Comedy, were not strong enough to excite his Fire; and what seem'd Want of Qualification, was only Absence of Impression. He had a Talent of discovering the Passions where they lay hid in some celebrated Parts by the injudicious Practice of other Actors; when he had discover'd, he soon grew able to express them: And his Secret for attaining this great Lesson of the Theatre, was an Adaption of his Looks to his Voice, by which artful Imitation of Nature, the Variations in the Sound of his Words gave Propriety to every Change in his Countenance: So that it was Booth's Excellence to be heard and seen the same, whether as the pleas'd, the griev'd, the pitying, the reproachful, or the angry. His Gesture, or, as it is commonly call'd, his Action, was but the Result and necessary Consequence of his Dominion over his Voice and Countenance; for having, by a Concurrence of Two such Causes, impressed his Imagination with such a Stamp and Spirit of Passion, his Nerves obey'd the Impulse by a kind of natural Dependency, or relaxed or braced successively into all that fine Expressiveness with which he painted what he spoke without Restraint, or Affectation.

As a Proof of Mr. Booth's Learning, I am desired to insert the Latin Inscription wrote by him on the Death of Mr. Smith[m] the Actor, with a short Account of him, as I receiv'd it from Mr. Benjamin Husband.

Scenicus eximius,

Regnante Carolo Secundo:

Bettertono Coætaneus & Amicus,

Nec non propemodum Æqualis:

Haud ignobile stirpe oriundus,

Nec Literarum rudis Humaniorum,

Rem Scenicam

Per multos feliciter Annos Administravit,

Justoque moderamine, & morum suavitate,

Omnium intra Theatrum

Observantiam, extra Theatrum laudem,

Upique benevolentiam & amoruem, fibi conciliavit.

In English,

An excellent Actor

Flourished in the Reign of Charles the Second:

Betterton's Cotemporary and Friend,

And very near him in Merit:

Sprung from a genteel Family,

And no Stranger to Literature.

In the Management of the Theatre

He acquitted himself many Years, with deserved Success;

And, by a just Deportment, and Sweetness of Temper,

Gained the Respect of all within the Theatre,

The Applause of those without;

And every-where claimed the Friendship

And Affection of Mankind.

I shall give a Couple of Songs as a Specimen of his Taste in ENglish Poetry, among many that do not occur to my Memory. The Source of them both sprung from his growing Passion for the amiable Miss Santlow, before their Marriage.

The First Song.

Can then a Look create a Thought

Which Time can ne'er remove?

Yes, foolish Heart, again thou'rt caught,

Again thou bleed'st for Love.She sees the Conquest of her Eyes,

Nor heals the Wounds she gave;

She smiles whene'er my Blushes rise,

And, sighing, shuns her Slave.Then, Swain, be bold! and still adore her,

Still the flying Fair persue:

Love, and Friendship, still implore her,

Pleading Night and Day for you.

The Second Song.

I.

Sweet are the Charms of her I love,

More fragrant than the Damsk Rose;

Soft as the Down of Turtle-DOve,

Gentle as Winds when Zephyr blows;

Refreshing as descending Rains,

On Sun-burnt Climes, and thirsty Plains.II.

True as the Needle to the Pole,

Or as the Dial to the Sun;

Constant as gliding Waters roll,

Whose swelling Tides obey the Moon:

From ev'ry other Charmer free,

My Life, and Love, shall follow thee.III.

The Lamb the flow'ry Thyme devours,

The Dam the tender Kind pursues;

Sweet Philomel, in shady Bow'rs

With verdant Spring her Notes renews:

All follow what they most admire,

As I pursue my Soul's Desire.IV.

Nature must change her beauteous Face,

And vary as the Seasons rise;

As Winter to the Spring gives Place,

Summer th' Approach of Autumn flies:

No Change on Love the Seasons bring,

Love only knows perpetual Spring.V.

Devouring Time, with stealing Pace,

Makes lofty Oaks and Cedars bow;

And Marble Tow'res, and Gates of Brass,

In his rude March he levels low:

But Time, destroying far and wide,

Love from the Soul can ne'er divide.VI.

Death, only, with his cruel Dart,

The gentle Godhead can remove;

And drive him from the bleeding Heart,

To mingle with the Blest above;

Where, known to all his Kindred Train,

He finds a lasting Rest from Pain.VII.

Love, and his Sister fair, the Soul,

Twin-born from Heav'n together came;

Love will the Universe controul,

When dying Seasons lose their Name:

Divine Abodes shall own his Pow'r,

When Time, and Death, shall be no more.

[1] The Composition for blackening the Face are Ivory-black and Pomatum, which is, with some Pains, clean'd with fresh Butter.

[m] This Gentleman, Mr. Smith, was zealously attach'd to the Interest of King James the Second, and served in his Army as a Volunteer, with Two Servants. After the Abdication, Mr. Smith return'd to the Theatre, by the Persuasion of many Friends, and the Desire of the Town, who admired his Performance. The first Character he chose to appear in was that of Wilmore in the Rover, his original Part in that Comedy; but, being informed that he should be maltreated on account of his Principles, he gave Orders for the Curtain to drop, if any Disturbance should come from the Audience. Accordingly the Play began in the utmost Tranquillity; but when Mr. Smith entered in the First Act, the Storm began with the usual Noise upon such Occasions (an Uproar not unknown to all Frequenters of Theatres, and by Time mightily improved by a particular Set that delight in that agreeable Harmony, as pleasing to the Ear, as a Sow-gelder's Horn, that sets all the Village Curs to imitate the Sound); Mr. Smith gave the Signal, the Curtain dropp'd, and the Audience dismiss'd. No Persuasions could prevail upon him to appear on the Stage again, till that great Poet, Mr. Congreve, had wrote his Comedy of Love for Love, which was in the Year 1695, more than three Years void from the above Accident. This celebrated Author prevailed upon several Persons of the First Rank to move Mr. Smith to appear in the Character of Scandal in that excellent Comedy: But he yielded more to the Persuasions of his sincere Friends, Mr. Betterton and Mrs. Barry, and accepted teh Part; and his inimitable Performance added one Grace to the Play. He took his Station in many Plays afterwards, for, I think, three Years. He died of a Cold, occasion'd by a violent Fit of the Cramp; for when he was first seiz'd, he thre himself out of Bed, and remained so long before the Cramp left him (in that naked Condition), that a Cold fell upon his Lungs, a Fever ensu'd, and Death releas'd him in three Days after.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

BOOTH, BARTON (1681–1733), actor, was the youngest son of John Booth, a Lancashire squire, nearly related to the Earl of Warrington. Three years after his birth his father, whose estate was impaired, came to London and settled in Westminster. At nine years of age Booth was sent to Westminster School, then under the management of Dr. Busby. A taste for poetry soon developed itself. For Horace, according to a statement of Maittaire, who was at that time an usher in the school, he had ‘a particular good taste,’ and he delighted much ‘in repeating parts of plays and poems, especially from Shakespear and Milton.' ‘In his latter plays,’ continues Maittaire, as quoted by Theophilus Cibber in his ‘Life of Booth' (p. 2), ‘ I have heard him repeat many passages from the "Paradise Lost" and "Samson Agonistes," &c., with such feeling, force, and natural harmony as might have waked the lethargic and made even the giddy attentive. A performance of Pamphilus in a customary representation of the ‘Andria’ of Terence attracted much attention to Booth, secured him the consideration of Dr. Busby and his successor Dr. Knipe, and filled him with stage fancies. When, accordingly, it was proposed to remove him to Trinity College, Cambridge, preparatory to his entering the church, he took motion on his own behalf with a view to adopting the stage as a profession. An application to Betterton was unsuccessful, the great actor not caring, it is supposed, to encourage a youth of family to take a step distasteful to his friends. Booth accordingly proceeded in June 1698 to Dublin and offered his services to Ashbury, the lessee of Smock Alley Theatre. An untrustworthy account of Booth, which has been accepted by Galt in his ‘Lives of Actors,' represents him as having run away from Trinity College, Cambridge, joined a travelling company, and been the hero of some comic adventures. Ashbury gave the fugitive an engagement, or at least allowed him to appear. This he did in the character of Oroonoko, with sufficient success to obtain from the manager a much-needed douceur of five guineas. Records concerning the Irish stage are more untrustworthy even than those of the English. To this it must be attributed that Hitchcock's ‘Historical View of the Irish Stage’ mentions Booth, who, however, may possibly, though for many reasons it is improbable, have been another actor of the name, as playing about 1695—when he could only have been fourteen years of age—Colonel Bruce in ‘The Comical Revenge, or Love in a Tub, ‘Freeman in ‘She would if she could,' and Medley in ‘The Man of Mode,' all by Etherege. After two seasons in Dublin Booth determined to try his fortune in London. He quitted Ireland accordingly, and, furnished with an introduction from Lord Fitzharding, lord of the bedchamber to Prince George of Denmark, made a second application to Betterton. Bowman the actor was also instrumental in bringing him to the notice of Betterton. This time Booth was successful. Before his first appearance at Lincoln's Inn Fields which took place in 1700 as Maximus in ‘Valentinian,’ he is supposed to have played in a country company. So complete and immediate was the triumph of Booth, that Rowe, who in the year 1700 brought out an 'Ambitious Stepmother,' confided to him the part of Artabun. At Lincoln’s Inn Fields Booth, remained playing secondary characters until 1704, in which year he married Frances Barkham, a daughter of Sir William Barkham, bt., of Norfolk. This lady died about 1710 without issue. A free liver at first, Booth took warning by the contempt and distress in which drunkenness had plunged Powell, forswore all excess in drinking, and had resolution enough to keep his vow. On 17 April 1705 Booth accompanied Betterton to the new theatre erected by Sir John Vanbrugh in the Haymarket; on 15 Jan. 1708 he appeared with the associated companies at Drury Lane, playing Ghost to the Hamlet of Wilks. In the year 1713 the star of Booth rose in the ascendant. Although kept in the background by Wilks, who perpetually subordinated him to Mills, an actor in every way his inferior, Booth had acquired a reputation as a tragedian. Downes, in his ‘Roscius Anglicanus,’ first published in 1708, speaks of him quaintly as ‘a gentleman of liberal education, of form venust; of mellifluent pronunciation, having proper gesticulations, which are graceful attendants of true elocution; of his time a most complete tragedian.' It is difficult to realise in what characters, beyond the Ghost in ‘Hamlet,’ in which he was supposed to be unrivalled, his tragic reputation had at that time been made. Hippolitus in the ‘Phædra and Hippolitus' of Smith is almost the only part of primary importance which had been trusted to him. Not till some years later (17 March 1712) did his performance of Pyrrhus in ‘The Distressed Mother.' Philips's contemptible rendering of Racine's ‘Phédre,' win him the highest honours. A year later (14 April 1713) his impersonation of Cato in Addison’s tragedy brought him to the front of his profession. With the performance of Cato, Booth’s reputation reached a climax. No subsequent performance did anything to raise it, though such characters as Jaffier, Melantius (in the ‘Maids Tragedy‘), Bajazet, Timon of Athens, and Lear now came to him. Something like a reaction, indeed, very easy to understand in the case of a success so rapid, set in, and has since been maintained. No player of reputation equal to Booth has obtained from subsequent times more grudging recognition. Cato was the means of bringing Booth fortune as well as honour. He had always received a large amount of aristocratic patronage, and when acting at Windsor found always, as he stated to Chetwood (General History of the Stage, pp. 92–3), a carriage and six horses provided by some nobleman to ‘whip’ him back to London. To the favour with which Booth was regarded by Lord Bolingbroke it is attributed that Colley Cibber, Doggett, and Wilks, the managers of Drury Lane, received the command of Queen Anne to admit him into the management. Of the revolt which this exercise of royal authority occasioned, Cibber, in his ‘Apology,' gives a long description, The only title on which Wilks, Doggett, and Cibber held their license was their professional superiority. Cibber, writing long after the event, admits that Booth had likewise‘s manifest merit.’ The years which followed Booth’s promotion to the post of manager were undistinguished by many events outside the performance of the principal characters in the drama. An intrigue with Susan Mountfort, the daughter of Mrs. Mountfort, brought upon Booth accusations of mercenariness, from which his biographers have triumphantly acquitted him. In 1719 he married Hester Santlow, a dancer of more beauty than reputation, who was said to have lived under the protection of the Duke of Marlborough, and subsequently of Secretary Craggs. Mrs. Santlow had a considerable fortune, and to this was attributed the act of Booth, who, as Dennis states in his ‘Letter on the Character and Conduct of Sir John Edgar,' knew of her irregular life. A perusal of Booth's poems to his mistress shows, however, that he was genuinely enamoured. Contrary to expectation, the marriage proved signally happy. Booth in his will speaks in handsome terms of his wife, to whom he left his whole estate, consisting of her own money, diminished by about one-third; and she, forty-five years after his death, in her ninety-third year, erected a monument to his memory in Westminster Abbey. As an actress Mrs. Booth was pleasing rather than great. Davies, in his ‘Dramatic Miscellanies,’ says of her Ophelia that ‘figure, voice, and department in this part, raised in the minds of the spectators an amiable picture of an innocent, unhappy maid, but she went no farther’ (iii. 126–7). Theophilus Cibber speaks of her with enthusiasm, so far as regards her moral qualities: ‘she was a beautiful woman, lovely in her countenance, delicate in her form, a pleasing actress, and a most admirable dancer; generally allowed, in the last-mentioned part of her profession, to have been superior to all who had been seen before her, and perhaps she has not been since excelled. But, to do her justice, she was more than all this; she was an excellent good wife; which he has frequently, in my hearing, talked of in such a manner as nothing but a sincere, heartfelt gratitude could express; and I was often an eye-witness (our families being intimate) of their conjugal felicity‘ (Life of Barton Booth, p. 33). Booth continued his theatrical duties till 1727, when he was seized with a fever which lasted six-and-forty days. He returned to the stage and appeared on 19 Dec. as Julio in ‘The Double Falsehood’ of Theobald. He played also in the winter and spring in ‘Cato,’ ‘The Double falsehood,’ and ‘Henry VIII.' A relapse ensued, his illness settled into jaundice, and he appeared no more upon the stage. In spite of the abstinence from drink, which itself was only comparative, he seems to have been a gourmand. He went to Belgium and afterwards lived at Hampstead in the vain pursuit of health, and died on Tuesday, 10 May 1733. In accordance with his own wishes, he was buried at Cowley near Uxbridge.

Highly favourable verdicts have been passed upon Booth by competent judges. Davies preferred his Brutus to that of Quin, but judged his Lear inferior on the whole to that of Garrick, though worthy of a comparison with it. Booth's Henry VIII, in which he succeeded Betterton, Davies greatly admired, as, he states, did Macklin and Quin. Theophilus Cibber says he had 'all the advantages that art or nature could bestow to make an admirable actor,' speaks in warm praise of his voice and perfect articulation, and dwells with enthusiasm upon his deportment, his dignity, and majesty. He praises especially his Hotspur and Lothario. Aaron Hill, in a letter addressed to Victor, one of Booth’s biographers, speaks warmly of Booth’s ‘gestures,’ of his ‘peculiar grace,’ his ‘elegant negligence,’ and his ‘talent of discovering the passions where they lay hid in some celebrated parts.’ Colley Cibber sneers at Booth, but his motives in so doing are transparently interested. Booth is the author of ‘The Death of Dido, a Masque,’ London, 8vo, 1716, said in the ‘Biographia Britannica’ to have been played in the same year at Drury Lane. He also wrote some poems, and a Latin epitaph on Smith the actor. The poems have a certain conventional sprightliness and fancy, but are in no sense remarkable.

[Genest's History of the Stage; Baker, Reed, and Jones's Biographia Dramatica; Colley Cibber's Apology by Bellchamber, 1822; Davies's Dramatic Miscellanies, 1784; Chetwood's General History of the Stage, 1749; Theophilus Cibber's Life and Character of Barton Booth, published by an intimate acquaintance of Mr. Booth (B. Victor), by consent of his wife. 1733.]

J. K.