Plato (428/427? – 348/347 BCE)

from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The following article from Wikipedia is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0. It was fetched on April 25, 2025, 10:01 p.m. Contribute to this article on Wikipedia.

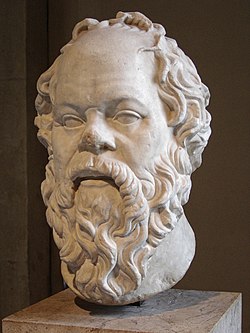

Plato | |

|---|---|

Roman copy of a portrait bust c. 370 BC | |

| Born | 428/427 or 424/423 BC |

| Died | 348/347 BC Athens |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | Ancient Greek philosophy |

| Notable students | Aristotle |

| Main interests | Epistemology, Metaphysics Political philosophy |

| Notable works | |

| Notable ideas | |

Plato (/ˈpleɪtoʊ/ PLAY-toe;[1] Greek: Πλάτων, Plátōn; born c. 428–423 BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the written dialogue and dialectic forms. He influenced all the major areas of theoretical philosophy and practical philosophy, and was the founder of the Platonic Academy, a philosophical school in Athens where Plato taught the doctrines that would later become known as Platonism.

Plato's most famous contribution is the theory of forms (or ideas), which aims to solve what is now known as the problem of universals. He was influenced by the pre-Socratic thinkers Pythagoras, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, although much of what is known about them is derived from Plato himself.[a]

Along with his teacher Socrates, and his student Aristotle, Plato is a central figure in the history of Western philosophy.[b] Plato's complete works are believed to have survived for over 2,400 years—unlike that of nearly all of his contemporaries.[5] Although their popularity has fluctuated, they have consistently been read and studied through the ages.[6] Through Neoplatonism, he also influenced both Christian and Islamic philosophy.[c] In modern times, Alfred North Whitehead said: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[7]

Biography

Plato was born in Athens or Aegina, between 428[8] and 423 BC.[9][10] He was a member of an aristocratic and influential family.[11][d][14] His father was Ariston,[e][14] who may have been a descendant of two kings, Codrus and Melanthus.[f][15][16] His mother was Perictione, descendant of Solon,[17] a statesman credited with laying the foundations of Athenian democracy.[18][19][20] Plato had two brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantus, a sister, Potone,[21] and a half brother, Antiphon.[22]

There is a traditional story that Plato is a nickname. According to Diogenes Laërtius, writing hundreds of years after Plato's death, his birth name was Aristocles (Ἀριστοκλῆς), meaning 'best reputation'.[21][g] Plátōn (Ancient Greek: Πλάτων) sounds like "Platus" or "Platos", meaning 'broad', and according to Diogenes' sources, Plato gained his nickname either from his wrestling coach, Ariston of Argos, who dubbed him "broad" on account of his chest and shoulders, or he gained it from the breadth of his eloquence, or his wide forehead.[21][23][24] According to the traditional story, Plato was originally named after his paternal grandfather, supposedly called Aristocles; the name "Plato" was only used as a nickname; and the philosopher could not have been named "Plato" because that name does not occur previously in his family line.[10] Modern scholarship, however, tends to reject the "Aristocles" story.[25][26][10][27][h]

Plato may have travelled to Italy, Sicily, Egypt, and Cyrene.[30] At 40, he founded a school of philosophy, the Academy. It was located in Athens, on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus,[31] named after an Attic hero in Greek mythology. The Academy operated until it was destroyed by Sulla in 84 BC. Many philosophers studied at the Academy, the most prominent being Aristotle.[32][33]

According to Diogenes Laërtius, throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse, where he attempted to replace the tyrant Dionysius,[34] with Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse, whom Plato had recruited as one of his followers, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato almost faced death, but was sold into slavery. Anniceris, a Cyrenaic philosopher, bought Plato's freedom for twenty minas,[35] and sent him home. Philodemus however states that Plato was sold as a slave as early as in 404 BC, when the Spartans conquered Aegina, or, alternatively, in 399 BC, immediately after the death of Socrates.[36] After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's Seventh Letter, Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II, who seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but eventually became suspicious of their motives, expelling Dion and holding Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse and Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and rule Syracuse, before being usurped by Callippus, a fellow disciple of Plato.

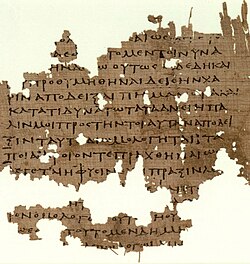

A variety of sources have given accounts of Plato's death. One story, based on a mutilated manuscript,[37] suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a young Thracian girl played the flute to him.[38] Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account is based on Diogenes Laërtius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a third-century Alexandrian.[39] According to Tertullian, Plato simply died in his sleep.[39] According to Philodemus, Plato was buried in the garden of his academy in Athens, close to the sacred shrine of the Muses.[36] In 2024, a scroll found at Herculaneum was deciphered, that supported some previous theories. The papyrus says that before death Plato "retained enough lucidity to critique the musician for her lack of rhythm", and that he was buried "in his designated garden in the Academy of Athens".[40]

Influences

Socrates

Plato never speaks in his own voice in his dialogues; every dialogue except the Laws features Socrates, although many dialogues, including the Timaeus and Statesman, feature him speaking only rarely. Leo Strauss notes that Socrates' reputation for irony casts doubt on whether Plato's Socrates is expressing sincere beliefs.[41] Xenophon's Memorabilia and Aristophanes's The Clouds seem to present a somewhat different portrait of Socrates from the one Plato paints. Aristotle attributes a different doctrine with respect to Forms to Plato and Socrates.[42] Aristotle suggests that Socrates' idea of forms can be discovered through investigation of the natural world, unlike Plato's Forms that exist beyond and outside the ordinary range of human understanding.[43] The Socratic problem concerns how to reconcile these various accounts. The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of contention among scholars.[44]

Pythagoreanism

Although Socrates influenced Plato directly, the influence of Pythagoras, or in a broader sense, the Pythagoreans, such as Archytas, also appears to have been significant. Aristotle and Cicero both claimed that the philosophy of Plato closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans.[45][46] According to R. M. Hare, this influence consists of three points:

- The platonic Republic might be related to the idea of "a tightly organized community of like-minded thinkers", like the one established by Pythagoras in Croton.

- The idea that mathematics and, generally speaking, abstract thinking is a secure basis for philosophical thinking as well as "for substantial theses in science and morals".

- They shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world".[47][48]

Pythagoras held that all things are number, and the cosmos comes from numerical principles. He introduced the concept of form as distinct from matter, and that the physical world is an imitation of an eternal mathematical world. These ideas were very influential on Heraclitus, Parmenides and Plato.[49][50]

Heraclitus and Parmenides

The two philosophers Heraclitus and Parmenides, influenced by earlier pre-Socratic Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Xenophanes,[51] departed from mythological explanations for the universe and began the metaphysical tradition that strongly influenced Plato and continues today.[50] Heraclitus viewed all things as continuously changing, that one cannot "step into the same river twice" due to the ever-changing waters flowing through it, and all things exist as a contraposition of opposites. According to Diogenes Laërtius, Plato received these ideas through Heraclitus' disciple Cratylus.[52] Parmenides adopted an altogether contrary vision, arguing for the idea of a changeless, eternal universe and the view that change is an illusion.[50] Plato's most self-critical dialogue is the Parmenides, which features Parmenides and his student Zeno, which criticizes Plato's own metaphysical theories. Plato's Sophist dialogue includes an Eleatic stranger. These ideas about change and permanence, or becoming and Being, influenced Plato in formulating his theory of Forms.[52]

Philosophy

In Plato's dialogues, Socrates and his company of disputants had something to say on many subjects, including several aspects of metaphysics. These include religion and science, human nature, love, and sexuality. More than one dialogue contrasts perception and reality, nature and custom, and body and soul. Francis Cornford identified the "twin pillars of Platonism" as the theory of Forms, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the doctrine of immortality of the soul.[53]

The Forms

In the dialogues Socrates regularly asks for the meaning of a general term (e. g. justice, truth, beauty), and criticizes those who instead give him particular examples, rather than the quality shared by all examples. "Platonism" and its theory of Forms (also known as 'theory of Ideas') denies the reality of the material world, considering it only an image or copy of the real world. According to this theory of Forms, there are these two kinds of things: the apparent world of material objects grasped by the senses, which constantly changes, and an unchanging and unseen world of Forms, grasped by reason (λογική). Plato's Forms represent types of things, as well as properties, patterns, and relations, which are referred to as objects. Just as individual tables, chairs, and cars refer to objects in this world, 'tableness', 'chairness', and 'carness', as well as e.g. justice, truth, and beauty refer to objects in another world. One of Plato's most cited examples for the Forms were the truths of geometry, such as the Pythagorean theorem. The theory of Forms is first introduced in the Phaedo dialogue (also known as On the Soul), wherein Socrates disputes the pluralism of Anaxagoras, then the most popular response to Heraclitus and Parmenides.

The Soul

For Plato, as was characteristic of ancient Greek philosophy, the soul was that which gave life.[54] Plato advocates a belief in the immortality of the soul, and several dialogues end with long speeches imagining the afterlife. In the Timaeus, Socrates locates the parts of the soul within the human body: Reason is located in the head, spirit in the top third of the torso, and the appetite in the middle third of the torso, down to the navel.[55][56]

Furthermore, Plato evinces a belief in the theory of reincarnation in multiple dialogues (such as the Phaedo and Timaeus). Scholars debate whether he intends the theory to be literally true, however.[57] He uses this idea of reincarnation to introduce the concept that knowledge is a matter of recollection of things acquainted with before one is born, and not of observation or study.[58] Keeping with the theme of admitting his own ignorance, Socrates regularly complains of his forgetfulness. In the Meno, Socrates uses a geometrical example to expound Plato's view that knowledge in this latter sense is acquired by recollection. Socrates elicits a fact concerning a geometrical construction from a slave boy, who could not have otherwise known the fact (due to the slave boy's lack of education). The knowledge must be of, Socrates concludes, an eternal, non-perceptible Form.

Epistemology

Plato also discusses several aspects of epistemology. In several dialogues, Socrates inverts the common man's intuition about what is knowable and what is real. Reality is unavailable to those who use their senses. Socrates says that he who sees with his eyes is blind. While most people take the objects of their senses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who think that something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In the Theaetetus, he says such people are eu amousoi (εὖ ἄμουσοι), an expression that means literally, "happily without the muses".[59] In other words, such people are willingly ignorant, living without divine inspiration and access to higher insights about reality. Many have interpreted Plato as stating – even having been the first to write – that knowledge is justified true belief, an influential view that informed future developments in epistemology.[60] Plato also identified problems with the justified true belief definition in the Theaetetus, concluding that justification (or an "account") would require knowledge of difference, meaning that the definition of knowledge is circular.[61][62]

In the Sophist, Statesman, Republic, Timaeus, and the Parmenides, Plato associates knowledge with the apprehension of unchanging Forms and their relationships to one another (which he calls "expertise" in dialectic), including through the processes of collection and division.[63] More explicitly, Plato himself argues in the Timaeus that knowledge is always proportionate to the realm from which it is gained. In other words, if one derives one's account of something experientially, because the world of sense is in flux, the views therein attained will be mere opinions. Meanwhile, opinions are characterized by a lack of necessity and stability. On the other hand, if one derives one's account of something by way of the non-sensible Forms, because these Forms are unchanging, so too is the account derived from them. That apprehension of Forms is required for knowledge may be taken to cohere with Plato's theory in the Theaetetus and Meno.[64] Indeed, the apprehension of Forms may be at the base of the account required for justification, in that it offers foundational knowledge which itself needs no account, thereby avoiding an infinite regression.[65]

Ethics

Several dialogues discuss ethics including virtue and vice, pleasure and pain, crime and punishment, and justice and medicine. Socrates presents the famous Euthyphro dilemma in the dialogue of the same name: "Is the pious (τὸ ὅσιον) loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" (10a) In the Protagoras dialogue it is argued through Socrates that virtue is innate and cannot be learned, that no one does bad on purpose, and to know what is good results in doing what is good; that knowledge is virtue. In the Republic, Plato poses the question, "What is justice?" and by examining both individual justice and the justice that informs societies, Plato is able not only to inform metaphysics, but also ethics and politics with the question: "What is the basis of moral and social obligation?" Plato's well-known answer rests upon the fundamental responsibility to seek wisdom, wisdom which leads to an understanding of the Form of the Good. Plato views "The Good" as the supreme Form, somehow existing even "beyond being". In this manner, justice is obtained when knowledge of how to fulfill one's moral and political function in society is put into practice.[66]

Politics

The dialogues also discuss politics. Some of Plato's most famous doctrines are contained in the Republic as well as in the Laws and the Statesman. Because these opinions are not spoken directly by Plato and vary between dialogues, they cannot be straightforwardly assumed as representing Plato's own views.

Socrates asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul. The appetite/spirit/reason are analogous to the castes of society.[67]

- Productive (Workers) – the labourers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

- Protective (Warriors or Guardians) – those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the "spirit" part of the soul.

- Governing (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) – those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the "reason" part of the soul and are very few.

According to Socrates, a state made up of different kinds of souls will, overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy (rule by the honourable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny (rule by one person, rule by a tyrant).[68]

Rhetoric and poetry

| Part of a series on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

|

Several dialogues tackle questions about art, including rhetoric and rhapsody. Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the Phaedrus,[69] and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well. Scholars often view Plato's philosophy as at odds with rhetoric due to his criticisms of rhetoric in the Gorgias and his ambivalence toward rhetoric expressed in the Phaedrus. But other contemporary researchers contest the idea that Plato despised rhetoric and instead view his dialogues as a dramatization of complex rhetorical principles.[70][71][72] Plato made abundant use of mythological narratives in his own work;[73] It is generally agreed that the main purpose for Plato in using myths was didactic.[74] He considered that only a few people were capable or interested in following a reasoned philosophical discourse, but men in general are attracted by stories and tales. Consequently, then, he used the myth to convey the conclusions of the philosophical reasoning.[75] Notable examples include the story of Atlantis, the Myth of Er, and the Allegory of the Cave.

Definition of humanity

When considering the taxonomic definition of mankind, Plato proposed the term "featherless biped",[76] and later ζῷον πολιτικόν (zōon politikon), a "political" or "state-building" animal (Aristotle's term, based on Plato's Statesman).

Diogenes the Cynic took issue with the former definition, reportedly producing a recently plucked chicken with the exclamation of "Here is Plato’s man!"[77] (variously translated as "Behold, a man!"; "Here is a human!" etc.).

Works

Themes

Plato never presents himself as a participant in any of the dialogues, and with the exception of the Apology, there is no suggestion that he heard any of the dialogues firsthand. Some dialogues have no narrator but have a pure "dramatic" form, some dialogues are narrated by Socrates himself, who speaks in the first person. The Symposium is narrated by Apollodorus, a Socratic disciple, apparently to Glaucon. Apollodorus assures his listener that he is recounting the story, which took place when he himself was an infant, not from his own memory, but as remembered by Aristodemus, who told him the story years ago. The Theaetetus is also a peculiar case: a dialogue in dramatic form embedded within another dialogue in dramatic form. Some scholars take this as an indication that Plato had by this date wearied of the narrated form.[78] In most of the dialogues, the primary speaker is Socrates, who employs a method of questioning which proceeds by a dialogue form called dialectic. The role of dialectic in Plato's thought is contested but there are two main interpretations: a type of reasoning and a method of intuition.[79] Simon Blackburn adopts the first, saying that Plato's dialectic is "the process of eliciting the truth by means of questions aimed at opening out what is already implicitly known, or at exposing the contradictions and muddles of an opponent's position."[79] Karl Popper, on the other hand, claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances".[80] Other researchers also emphasise that Plato's philosophy has a strong religious component, e. g. in that philosophising is seen as a means of ascending to a higher level of consciousness.[81]

Textual sources and history

During the early Renaissance, the Greek language and, along with it, Plato's texts were reintroduced to Western Europe by Byzantine scholars. Some 250 known manuscripts of Plato survive.[82] In September or October 1484 Filippo Valori and Francesco Berlinghieri printed 1025 copies of Ficino's translation, using the printing press at the Dominican convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli.[83] The 1578 edition[84] of Plato's complete works published by Henricus Stephanus (Henri Estienne) in Geneva also included parallel Latin translation and running commentary by Joannes Serranus (Jean de Serres). It was this edition which established standard Stephanus pagination, still in use today.[85] The text of Plato as received today apparently represents the complete written philosophical work of Plato, based on the first century AD arrangement of Thrasyllus of Mendes.[86][87] The modern standard complete English edition is the 1997 Hackett Plato: Complete Works, edited by John M. Cooper.[88][89]

Authenticity

Thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters (the Epistles) have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these. Jowett[90] mentions in his Appendix to Menexenus, that works which bore the character of a writer were attributed to that writer even when the actual author was unknown. The works taken as genuine in antiquity but are now doubted by at least some modern scholars are: Alcibiades I (*),[i] Alcibiades II (‡), Clitophon (*), Epinomis (‡), Letters (*), Hipparchus (‡), Menexenus (*), Minos (‡), Lovers (‡), Theages (‡) The following works were transmitted under Plato's name in antiquity, but were already considered spurious by the 1st century AD: Axiochus, Definitions, Demodocus, Epigrams, Eryxias, Halcyon, On Justice, On Virtue, Sisyphus.

Chronology

No one knows the exact order Plato's dialogues were written in, nor the extent to which some might have been later revised and rewritten. The works are usually grouped into Early, Middle, and Late period; The following represents one relatively common division amongst developmentalist scholars.[91]

- Early: Apology, Charmides, Crito, Euthyphro, Gorgias, Hippias Minor, Hippias Major, Ion, Laches, Lysis, Protagoras

- Middle: Cratylus, Euthydemus, Meno, Parmenides, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Republic, Symposium, Theatetus

- Late: Critias, Sophist, Statesman, Timaeus, Philebus, Laws.[92]

Brickhouse and Smith incorporate "early-transitional" and "later-transitional" phases between these divisions.[2]

Whereas those classified as "early dialogues" often conclude in aporia, the so-called "middle dialogues" provide more clearly stated positive teachings that are often ascribed to Plato such as the theory of Forms. The remaining dialogues are classified as "late" and are generally agreed to be difficult and challenging pieces of philosophy.[93] It should, however, be kept in mind that many of the positions in the ordering are still highly disputed, and also that the very notion that Plato's dialogues can or should be "ordered" is by no means universally accepted,[94][j] though Plato's works are still often characterized as falling at least roughly into three groups stylistically.[2]

Legacy

Unwritten doctrines

Plato's unwritten doctrines are,[96][97][98] according to some ancient sources, the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public, although many modern scholars doubt these claims. A reason for not revealing it to everyone is partially discussed in Phaedrus where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as faulty, favouring instead the spoken logos: "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful ... will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually."[99] It is, however, said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture On the Good (Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ), in which the Good (τὸ ἀγαθόν) is identified with the One (the Unity, τὸ ἕν), the fundamental ontological principle.

The first witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in Timaeus] of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called unwritten teachings (Ancient Greek: ἄγραφα δόγματα, romanized: agrapha dogmata)."[100] In Metaphysics he writes: "Now since the Forms are the causes of everything else, he [i.e. Plato] supposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Accordingly, the material principle is the Great and Small [i.e. the Dyad], and the essence is the One (τὸ ἕν), since the numbers are derived from the Great and Small by participation in the One".[101] "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence, and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in everything else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also tells us what the material substrate is of which the Forms are predicated in the case of sensible things, and the One in that of the Forms – that it is this the duality (the Dyad, ἡ δυάς), the Great and Small (τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν). Further, he assigned to these two elements respectively the causation of good and of evil".[101]

The most important aspect of this interpretation of Plato's metaphysics is the continuity between his teaching and the Neoplatonic interpretation of Plotinus[k] or Ficino[l] which has been considered erroneous by many but may in fact have been directly influenced by oral transmission of Plato's doctrine. A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy in 1930.[102] All the sources related to the ἄγραφα δόγματα have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as Testimonia Platonica.[103]

Reception

Plato's thought is often compared with that of his most famous student, Aristotle, whose reputation during the Western Middle Ages so completely eclipsed that of Plato that the Scholastic philosophers referred to Aristotle as "the Philosopher". The only Platonic work known to western scholarship was Timaeus, until translations were made after the fall of Constantinople, which occurred during 1453.[104] However, the study of Plato continued in the Byzantine Empire, the Caliphates during the Islamic Golden Age, and Spain during the Golden age of Jewish culture. Plato is also referenced by Jewish philosopher and Talmudic scholar Maimonides in his Guide for the Perplexed.

The works of Plato were again revived at the times of Islamic Golden ages with other Greek contents through their translation from Greek to Arabic. Neoplatonism was revived from its founding father, Plotinus.[105] Neoplatonism, a philosophical current that permeated Islamic scholarship, accentuated one facet of the Qur’anic conception of God—the transcendent—while seemingly neglecting another—the creative. This philosophical tradition, introduced by Al-Farabi and subsequently elaborated upon by figures such as Avicenna, postulated that all phenomena emanated from the divine source.[106][107] It functioned as a conduit, bridging the transcendental nature of the divine with the tangible reality of creation. In the Islamic context, Neoplatonism facilitated the integration of Platonic philosophy with mystical Islamic thought, fostering a synthesis of ancient philosophical wisdom and religious insight.[106] Inspired by Plato's Republic, Al-Farabi extended his inquiry beyond mere political theory, proposing an ideal city governed by philosopher-kings.[108] Many of these commentaries on Plato were translated from Arabic into Latin, in which form they influenced medieval scholastics.[109]

During the Renaissance, Gemistos Plethon brought Plato's original writings to Florence from Constantinople in the century of its fall. Many of the greatest early modern scientists and artists who broke with Scholasticism, with the support of the Plato-inspired Lorenzo (grandson of Cosimo), saw Plato's philosophy as the basis for progress in the arts and sciences. The 17th century Cambridge Platonists sought to reconcile Plato's more problematic beliefs, such as metempsychosis and polyamory, with Christianity.[110] By the 19th century, Plato's reputation was restored, and at least on par with Aristotle's. Plato's influence has been especially strong in mathematics and the sciences. Plato's resurgence further inspired some of the greatest advances in logic since Aristotle, primarily through Gottlob Frege. Albert Einstein suggested that the scientist who takes philosophy seriously would have to avoid systematization and take on many different roles, and possibly appear as a Platonist or Pythagorean, in that such a one would have "the viewpoint of logical simplicity as an indispensable and effective tool of his research."[111] British philosopher Alfred North Whitehead said: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[7][112]

Criticism

Many recent philosophers have also diverged from what some would describe as ideals characteristic of traditional Platonism. Friedrich Nietzsche notoriously attacked Plato's "idea of the good itself" along with many fundamentals of Christian morality, which he interpreted as "Platonism for the masses" in Beyond Good and Evil (1886). Martin Heidegger argued against Plato's alleged obfuscation of Being in his incomplete tome, Being and Time (1927). Karl Popper argued in the first volume of The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) that Plato's proposal for a "utopian" political regime in the Republic was prototypically totalitarian; this has been disputed.[113][114] Edmund Gettier famously demonstrated the Gettier problem for the justified true belief account of knowledge. That the modern theory of justified true belief as knowledge, which Gettier addresses, is equivalent to Plato's is, however, accepted only by some scholars but rejected by others.[115]

Notes

- ^ "Though influenced primarily by Socrates, to the extent that Socrates is usually the main character in many of Plato's writings, he was also influenced by Heraclitus, Parmenides, and the Pythagoreans."[2]

- ^ "...the subject of philosophy, as it is often conceived – a rigorous and systematic examination of ethical, political, metaphysical, and epistemological issues, armed with a distinctive method – can be called his invention."[3][4]

- ^ Two influential examples of said cultures are Augustine of Hippo, and Al-Farabi.

- ^ He was known to have worn earrings and finger rings during his youth as a sign of his noble descent.[12] The extent of Plato's affinity for jewelry while young was even characterized as "decadent" by Sextus Empiricus.[13]

- ^ According to Alexander Polyhistor, quoted by Diogenes Laërtius.

- ^ According to a tradition reported by Diogenes Laërtius, but disputed by Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Ariston himself traced his descent from these kings. Debra Nails writes, "If he claimed descent from Codrus and Melanthus, and thus from Poseidon (D. L. 3.1), that claim is not exploited in the dialogues."

- ^ From aristos and kleos

- ^ Plato always called himself Platon. Platon was a fairly common name (31 instances are known from Athens alone),[28] including people named before Plato was born. Robin Waterfield states that Plato was not a nickname, but a perfectly normal name, and "the common practice of naming a son after his grandfather was reserved for the eldest son", not Plato.[10] According to Debra Nails, Plato's grandfather was the Aristocles who was archon in 605/4.[29]

- ^ (*) if there is no consensus among scholars as to whether Plato is the author, and (‡) if most scholars agree that Plato is not the author of the work. The extent to which scholars consider a dialogue to be authentic is noted in Cooper 1997, pp. v–vi.

- ^ Increasingly in the most recent Plato scholarship, writers are skeptical of the notion that the order of Plato's writings can be established with any precision.[95]

- ^ Plotinus describes this in the last part of his final Ennead (VI, 9) entitled On the Good, or the One (Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ ἢ τοῦ ἑνός). Jens Halfwassen states in Der Aufstieg zum Einen' (2006) that "Plotinus' ontology – which should be called Plotinus' henology – is a rather accurate philosophical renewal and continuation of Plato's unwritten doctrine, i.e. the doctrine rediscovered by Krämer and Gaiser."

- ^ In one of his letters (Epistolae 1612) Ficino writes: "The main goal of the divine Plato ... is to show one principle of things, which he called the One (τὸ ἕν)", cf. Montoriola 1926, p. 147.

References

- ^ Jones 2006.

- ^ a b c Brickhouse & Smith

- ^ Kraut 2013

- ^ Duignan, Brian. "Plato and Aristotle: How Do They Differ?". Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023.

Plato (c. 428–c. 348 BCE) and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) are generally regarded as the two greatest figures of Western philosophy

- ^ Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D.S., eds. (1997): "Introduction."

- ^ Cooper 1997, p. vii.

- ^ a b Whitehead 1978, p. 39.

- ^ Wilamowitz-Moellendorff 2005, p. 46.

- ^ Nails 2002, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d Robin Waterfield: Plato of Athens. Oxford University Press, 2023.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, § 3

Nails 2002, p. 53

Wilamowitz-Moellendorff 2005, p. 46. - ^ Notopoulos, James A. (1940). "Porphyry's Life of Plato". Classical Philology. 35 (3): 284–293. doi:10.1086/362396. ISSN 0009-837X. JSTOR 264394. S2CID 161160877. Archived from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ Veres, Máté (1 January 2019). "Sextus Empiricus, Against Those in the Disciplines. Translated with an introduction and notes by Richard Bett (Oxford University Press, 2018)". International Journal for the Study of Skepticism. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Plato FAQ: Plato's real name". www.plato-dialogues.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, § 1.

- ^ U. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Plato, 46

- ^ Laërtius 1925, § 1,4.

- ^ Stanton, G. R. Athenian Politics c. 800–500 BC: A Sourcebook, Routledge, London (1990), p. 76.

- ^ Andrews, A. Greek Society (Penguin 1967) 197

- ^ E. Harris, A New Solution to the Riddle of the Seisachtheia, in The Development of the Polis in Archaic Greece, eds. L. Mitchell and P. Rhodes (Routledge 1997) 103

- ^ a b c Laërtius 1925, § 4.

- ^ Plato (1992). Republic. trans. G. M. A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett. p. viii. ISBN 0-87220-137-6.

- ^ Sedley, David, Plato's Cratylus, Cambridge University Press 2003, pp. 21–22 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Notopoulos 1939, p. 135

- ^ Notopoulos 1939, pp. 135–145

- ^ Debra Nails: "The People of Plato". Pg 243: "a tradition soundly refuted by Notopoulos"

- ^ Julia Annas: "Plato: A Very Short Introduction". Oxford University Press. "Plato's name was probably Plato."

- ^ Guthrie 1986, p. 12 (footnote).

- ^ Nails pg 244

- ^ McEvoy 1984.

- ^ Cairns 1961, p. xiii.

- ^ Dillon 2003, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Press 2000, p. 1.

- ^ Riginos 1976, p. 73.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, § 20.

- ^ a b Sabur, Rozina (24 April 2024). "Mystery of Plato's final resting place solved after 'bionic eye' penetrates 2,000-year-old scroll". The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ Riginos 1976, p. 194.

- ^ Schall 1996.

- ^ a b Riginos 1976, p. 195.

- ^ Tondo, Lorenzo (29 April 2024). "Plato's final hours recounted in scroll found in Vesuvius ash". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ Strauss 1964, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Metaphysics 987b1–11

- ^ McPherran, M.L. (1998). The Religion of Socrates. Penn State Press. p. 268.

- ^ Vlastos 1991.

- ^ Metaphysics, 1.6.1 (987a)

- ^ Tusc. Disput. 1.17.39.

- ^ R.M. Hare, Plato in C.C.W. Taylor, R.M. Hare and Jonathan Barnes, Greek Philosophers, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999 (1982), 103–189, here 117–119.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1991). History of Western Philosophy. Routledge. pp. 120–124. ISBN 978-0-415-07854-2.

- ^ Calian, Florin George (2021). Numbers, Ontologically Speaking: Plato on Numerosity. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-46722-4. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ a b c McFarlane, Thomas J. "Plato's Parmenides". Integralscience. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ John Palmer (2019). "Parmenides". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ a b Large, William. "Heraclitus". Arasite. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Francis Cornford, 1941. The Republic of Plato. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xxv.

- ^ See this brief exchange from the Phaedo: "What is it that, when present in a body, makes it living? – A soul." Phaedo 105c.

- ^ Plato, Timaeus 44d Archived 11 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine & 70 Archived 11 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dorter 2006, p. 360.

- ^ Jorgensen 2018 is perhaps the strongest opponent to interpretations on which Plato intends the theory literally. See Jorgensen, The Embodied Soul in Plato's Later Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- ^ Baird & Kaufmann 2008.

- ^ Theaetetus 156a

- ^ Fine 2003, p. 5.

- ^ Theaetetus 210a–b Archived 11 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McDowell 1973, p. 256.

- ^ Taylor 2011, pp. 176–187.

- ^ Lee 2011, p. 432.

- ^ Taylor 2011, p. 189.

- ^ Republic, Book IV.

- ^ Blössner 2007, pp. 345–349.

- ^ Blössner 2007, p. 350.

- ^ Phaedrus (265a–c)

- ^ Kastely, James (2015). The Rhetoric of Plato's Republic. Chicago UP. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Bjork, Collin (2021). "Plato, Xenophon, and the Uneven Temporalities of Ethos in the Trial of Socrates". Philosophy & Rhetoric. 54 (3): 240–262. doi:10.5325/philrhet.54.3.0240. ISSN 0031-8213. JSTOR 10.5325/philrhet.54.3.0240. S2CID 244334227. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ Bengtson, Erik (2019). The epistemology of rhetoric: Plato, doxa and post-truth. Uppsala.

- ^ Chappel, Timothy. "Mythos and Logos in Plato". Open University. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Jorgensen, Chad. The Embodied Soul in Plato's Later Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018 page 199.

- ^ Partenie, Catalin. "Plato's Myths". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Plato (1975) [1925]. "The Statesman". Plato in Twelve Volumes with an English Translation. Vol. VIII (The Statesman, Philebus, Ion). Translated by Harold N[orth] Fowler. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-0-674-99182-8.

λέγω δὴ δεῖν τότε εὐθὺς τὸ πεζὸν τῷ δίποδι πρὸς τὸ τετράπουν γένος διανεῖμαι, κατιδόντα δὲ τἀνθρώπινον ἔτι μόνῳ τῷ πτηνῷ συνειληχὸς τὴν δίποδα ἀγέλην πάλιν τῷ ψιλῷ καὶ τῷ πτεροφυεῖ τέμνειν, [...]

[I say, then, that we ought at that time to have divided walking animals immediately into biped and quadruped, then seeing that the human race falls into the same division with the feathered creatures and no others, we must again divide the biped class into featherless and feathered, [...]] - ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of Philosophers 6.40. Quoted in "Plato and Diogenes debate featherless bipeds", Lapham's Quarterly.

- ^ Burnet 1928a, § 177.

- ^ a b Blackburn 1996, p. 104.

- ^ Popper 1962, p. 133.

- ^ Albert 1980.

- ^ Brumbaugh & Wells 1989.

- ^ Allen 1975, p. 12.

- ^ Platonis opera quae extant omnia edidit Henricus Stephanus, Genevae, 1578.

- ^ Suzanne 2009.

- ^ Cooper 1997, pp. viii–xii.

- ^ Irwin 2011, pp. 64 & 74

- ^ Fine 1999a, p. 482.

- ^ Complete Works – Philosophy Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ B Jowett, Menexenus: Appendix I (1st paragraph) Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ See Guthrie 1986; Vlastos 1991; Penner 1992; Kahn 1996; Fine 1999b.

- ^ Dodds 2004.

- ^ Cooper 1997, p. xiv.

- ^ Cooper 1997.

- ^ Kraut 2013; Schofield 2002; and Rowe 2006.

- ^ Rodriguez-Grandjean 1998.

- ^ Reale 1990. Cf. p. 14 and onwards.

- ^ Krämer 1990. Cf. pp. 38–47.

- ^ Phaedrus 276c

- ^ Physics 209b

- ^ a b Metaphysics 987b

- ^ Gomperz 1931.

- ^ Gaiser 1998.

- ^ C.U. M.Smith – Brain, Mind and Consciousness in the History of Neuroscience (page 1) Archived 23 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Springer Science & Business, 1 January 2014, 374 pages, Volume 6 of History, philosophy and theory of the life sciences SpringerLink : Bücher ISBN 94-017-8774-3 [Retrieved 27 June 2015]

- ^ Willinsky, John (2018). The Intellectual Properties of Learning: A Prehistory from Saint Jerome to John Locke (1st ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press (published 2 January 2018). pp. Chapter 6. ISBN 978-0226487922.

- ^ a b Aminrazavi, Mehdi (2021), "Mysticism in Arabic and Islamic Philosophy", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 17 March 2024

- ^ Paya, Ali (July 2014). "Islamic Philosophy: Past, Present and Future". Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements. 74: 265–321. doi:10.1017/S1358246114000113. ISSN 1358-2461.

- ^ Stefaniuk, Tomasz (5 December 2022). "Man in Early Islamic Philosophy – Al-Kindi and Al-Farabi". Ruch Filozoficzny. 78 (3): 65–84. doi:10.12775/RF.2022.023. ISSN 2545-3173.

- ^ See Burrell 1998 and Hasse 2002, pp. 33–45.

- ^ Carrigan, Henry L. Jr. (2012) [2011]. "Cambridge Platonists". The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9780470670606.wbecc0219. ISBN 978-1405157629.

- ^ Einstein 1949, pp. 683–684.

- ^ "A.N Whitehead on Plato". Columbia College. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023.

- ^ Gerasimos Santas (2010). “Understanding Plato’s Republic”. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 198. “The modern view that Plato's completely good city is some form of totalitarian society stems from... his criticisms of democracy and his censorship of the arts. This modern view is much contradicted by Plato's placing tyranny as the polar opposite of his completely good and just city. One has to understand this polar opposition before modern criticism can stick. Plato would have a hard time understanding Popper's criticisms; yes, Plato thought of his just society as anti-democratic, but the direct democracy Plato criticized is far removed from our representative democracies and does not exist anywhere among modern nation states, just as his ideal city does not. The moderns tend to think that if a regime is not democratic then it is totalitarian. Plato's completely good city is the rule of knowledge, not the rule of power, or honor, or wealth, or freedom and equality.”

- ^ Levinson, Ronald B. (1970). In Defense of Plato. New York: Russell and Russell. p. 20. "In spite of the high rating one must accord his initial intention of fairness, his hatred for the enemies of the 'open society,' his zeal to destroy whatever seems to him destructive of the welfare of mankind, has led him into the extensive use of what may be called terminological counterpropaganda. ... With a few exceptions in Popper's favor, however, it is noticeable that reviewers possessed of special competence in particular fields—and here Lindsay is again to be included—have objected to Popper's conclusions in those very fields. ... "Social scientists and social philosophers have deplored his radical denial of historical causation, together with his espousal of Hayek's systematic distrust of larger programs of social reform; historical students of philosophy have protested his violent polemical handling of Plato, Aristotle, and particularly Hegel; ethicists have found contradictions in the ethical theory ('critical dualism') upon which his polemic is largely based."

- ^ Fine 1979, p. 366.

Works cited

Primary sources (Greek and Roman)

- Apuleius, De Dogmate Platonis, I. See original text in Latin Library Archived 4 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Aristophanes, The Wasps. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 24 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Aristotle, Metaphysics. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 24 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cicero, De Divinatione, I. See original text in Latin library Archived 20 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:3. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:3. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.- Plato. . Translated by Jowett, Benjamin – via Wikisource. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 24 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Plato. . Translated by Jowett Benjamin – via Wikisource. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 8 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Plato (1903). Parmenides. Translated by Burnet, John. Oxford University. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2021. republished by: Crane, Gregory (ed.). "Perseus Digital Library Project". Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- Plato. . Translated by Jowett Benjamin – via Wikisource. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 8 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Plutarch (1683) [written in the late 1st century]. . Lives. Translated by Dryden, John – via Wikisource. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 8 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Seneca the Younger. . Translated by Richard Mott Gummere – via Wikisource. See original text in Latin Library Archived 24 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- Thucydides. . Translated by Crawley, Richard – via Wikisource., V, VIII. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 8 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- Xenophon, Memorabilia. See original text in Perseus Project Archived 24 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

Secondary sources

- Albert, Karl (1980). Griechische Religion und platonische Philosophie. Hamburg: Felix Meiner Verlag.

- Albert, Karl (1996). Einführung in die philosophische Mystik. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Allen, Michael J.B. (1975). "Introduction". Marsilio Ficino: The Philebus Commentary. University of California Press. pp. 1–58.

- Baird, Forrest E.; Kaufmann, Walter, eds. (2008). Philosophic Classics: From Plato to Derrida (Fifth ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-158591-1.

- Blackburn, Simon (1996). The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press.

- Bloom, Harold (1982). Agon. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Blössner, Norbert (2007). "The City-Soul Analogy". In Ferrari, G.R.F. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Plato's Republic. Translated by G.R.F. Ferrari. Cambridge University Press.

- Borody, W.A. (1998). "Figuring the Phallogocentric Argument with Respect to the Classical Greek Philosophical Tradition". Nebula, A Netzine of the Arts and Science. 13: 1–27. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). Merzbach, Uta C. (ed.). A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8.

- Brandwood, Leonard (1990). The Chronology of Plato's Dialogues. Cambridge University Press.

- Brickhouse, Thomas; Smith, Nicholas D. Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). "Plato". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Browne, Sir Thomas (1672). "XII". Pseudodoxia Epidemica. Vol. IV (6th ed.).

- Brumbaugh, Robert S.; Wells, Rulon S. (October 1989). "Completing Yale's Microfilm Project". The Yale University Library Gazette. 64 (1/2): 73–75. JSTOR 40858970.

- Burnet, John (1911). Plato's Phaedo. Oxford University Press.

- Burnet, John (1928a). Greek Philosophy: Part I: Thales to Plato. MacMillan.

- Burnet, John (1928b). Platonism. University of California Press.

- Cairns, Huntington (1961). "Introduction". In Hamilton, Edith; Cairns, Huntington (eds.). The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters. Princeton University Press.

- Burrell, David (1998). "Platonism in Islamic Philosophy". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 7. Routledge. pp. 429–430.

- Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D.S., eds. (1997). Plato: Complete Works. Hackett Publishing.

- Dillon, John (2003). The Heirs of Plato: A Study of the Old Academy. Oxford University Press.

- Dodds, E.R. (1959). Plato Gorgias. Oxford University Press.

- Dodds, E.R. (2004) [1951]. The Greeks and the Irrational. University of California Press.

- Dorter, Kenneth (2006). The Transformation of Plato's Republic. Lexington Books.

- Einstein, Albert (1949). "Remarks to the Essays Appearing in this Collective Volume". In Schilpp (ed.). Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist. The Library of Living Philosophers. Vol. 7. MJF Books. pp. 663–688.

- Fine, Gail (July 1979). "Knowledge and Logos in the Theaetetus". Philosophical Review. 88 (3): 366–397. doi:10.2307/2184956. ISSN 0031-8108. JSTOR 2184956. Reprinted in Fine 2003.

- Fine, Gail (1999a). "Selected Bibliography". Plato 1: Metaphysics and Epistemology. Oxford University Press. pp. 481–494.

- Fine, Gail (1999b). "Introduction". Plato 2: Ethics, Politics, Religion, and the Soul. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–33.

- Fine, Gail (2003). "Introduction". Plato on Knowledge and Forms: Selected Essays. Oxford University Press.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1980) [1968]. "Plato's Unwritten Dialectic". Dialogue and Dialectic. Yale University Press. pp. 124–155.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1997). "Introduzione". In Girgenti, Giuseppe (ed.). La nuova interpretazione di Platone. Milan: Rusconi Libri.

- Gaiser, Konrad (1980). "Plato's Enigmatic Lecture 'On the Good'". Phronesis. 25 (1): 5–37. doi:10.1163/156852880x00025.

- Gaiser, Konrad (1998). Reale, Giovanni (ed.). Testimonia Platonica: Le antiche testimonianze sulle dottrine non scritte di Platone. Milan: Vita e Pensiero. First published as "Testimonia Platonica. Quellentexte zur Schule und mündlichen Lehre Platons" as an appendix to Gaiser's Platons Ungeschriebene Lehre, Stuttgart, 1963.

- Gomperz, H. (1931). "Plato's System of Philosophy". In Ryle, G. (ed.). Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Philosophy. London. pp. 426–431.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Reprinted in Gomperz, H. (1953). Philosophical Studies. Boston: Christopher Publishing House 1953, pp. 119–124. - Grondin, Jean (2010). "Gadamer and the Tübingen School". In Gill, Christopher; Renaud, François (eds.). Hermeneutic Philosophy and Plato: Gadamer's Response to the Philebus. Academia Verlag. pp. 139–156.

- Guthrie, W.K.C. (1986). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 4, Plato: The Man and His Dialogues: Earlier Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31101-4.

- Hasse, Dag Nikolaus (2002). "Plato Arabico-latinus". In Gersh; Hoenen (eds.). The Platonic Tradition in the Middle Ages: A Doxographic Approach. De Gruyter. pp. 33–66.

- Irwin, T.H. (1979). Plato: Gorgias. Oxford University Press.

- Irwin, T.H. (2011). "The Platonic Corpus". In Fine, G. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford University Press.

- Jones, Daniel (2006). Roach, Peter; Hartman, James; Setter, Jane (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (17 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Kahn, Charles H. (1996). Plato and the Socratic Dialogue: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Form. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64830-1.

- Kierkegaard, Søren (1992). "Plato". The Concept of Irony. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02072-3.

- Krämer, Hans Joachim (1990). Catan, John R. (ed.). Plato and the Foundations of Metaphysics: A Work on the Theory of the Principles and Unwritten Doctrines of Plato with a Collection of the Fundamental Documents. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0433-1.

- Lee, M.-K. (2011). "The Theaetetus". In Fine, G. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford University Press. pp. 411–436.

- Kraut, Richard (11 September 2013). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Plato". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Lackner, D. F. (2001). "The Camaldolese Academy: Ambrogio Traversari, Marsilio Ficino and the Christian Platonic Tradition". In Allen; Rees (eds.). Marsilio Ficino: His Theology, His Philosophy, His Legacy. Brill.

- Meinwald, Constance Chu (1991). Plato's Parmenides. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McDowell, J. (1973). Plato: Theaetetus. Oxford University Press.

- McEvoy, James (1984). "Plato and The Wisdom of Egypt". Irish Philosophical Journal. 1 (2): 1–24. doi:10.5840/irishphil1984125. ISSN 0266-9080. Archived from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- Montoriola, Karl Markgraf von (1926). Briefe Des Mediceerkreises Aus Marsilio Ficino's Epistolarium. Berlin: Juncker.

- Nails, Debra (2002). The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87220-564-2.

- Nails, Debra (2006). "The Life of Plato of Athens". In Benson, Hugh H. (ed.). A Companion to Plato. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1521-6.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm (1967). "Vorlesungsaufzeichnungen". Werke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe (in German). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013912-9.

- Notopoulos, A. (April 1939). "The Name of Plato". Classical Philology. 34 (2): 135–145. doi:10.1086/362227. S2CID 161505593.

- Penner, Terry (1992). "Socrates and the Early Dialogues". In Kraut, Richard (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Plato. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–169.

- Meinwald, Constance (16 June 2023). "Plato". Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- "Plato". Encyclopaedic Dictionary The Helios Volume XVI (in Greek). 1952.

- "Plato". Suda. Archived from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2007.

- Popper, K. (1962). The Open Society and its Enemies. Vol. 1. London: Routledge.

- Press, Gerald Alan (2000). "Introduction". In Press, Gerald Alan (ed.). Who Speaks for Plato?: Studies in Platonic Anonymity. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1–14.

- Reale, Giovanni (1990). Catan, John R. (ed.). Plato and Aristotle. A History of Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 2. State University of New York Press.

- Reale, Giovanni (1997). Toward a New Interpretation of Plato. Washington, DC: CUA Press.

- Riginos, Alice (1976). Platonica : the anecdotes concerning the life and writings of Plato. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04565-1.

- Robinson, John (1827). Archæologica Græca (Second ed.). London: A. J. Valpy. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- Rodriguez-Grandjean, Pablo (1998). Philosophy and Dialogue: Plato's Unwritten Doctrines from a Hermeneutical Point of View. Twentieth World Congress of Philosophy. Boston. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Rowe, Christopher (2006). "Interpreting Plato". In Benson, Hugh H. (ed.). A Companion to Plato. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 13–24.

- Schall, James V. (Summer 1996). "On the Death of Plato". The American Scholar. 65. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Schofield, Malcolm (23 August 2002). Craig, Edward (ed.). "Plato". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Sedley, David (2003). Plato's Cratylus. Cambridge University Press.

- Slings, S.R. (1987). "Remarks on Some Recent Papyri of the Politeia". Mnemosyne. Fourth. 40 (1/2): 27–34. doi:10.1163/156852587x00030.

- Slings, S.R. (2003). Platonis Rempublicam. Oxford University Press.

- Smith, William (1870). "Plato". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- Strauss, Leo (1964). The City and the Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Suzanne, Bernard (8 March 2009). "The Stephanus edition". Plato and his dialogues. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- Szlezak, Thomas A. (1999). Reading Plato. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-18984-2.

- Tarán, Leonardo (1981). Speusippus of Athens. Brill Publishers.

- Tarán, Leonardo (2001). "Plato's Alleged Epitaph". Collected Papers 1962–1999. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-12304-5.

- Taylor, Alfred Edward (2001) [1937]. Plato: The Man and His Work. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-41605-2.

- Taylor, C.C.W. (2011). "Plato's Epistemology". In Fine, G. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford University Press. pp. 165–190.

- Vlastos, Gregory (1991). Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher. Cambridge University Press.

- Whitehead, Alfred North (1978). Process and Reality. New York: The Free Press.

- Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Ulrich von (2005) [1917]. Plato: His Life and Work (translated in Greek by Xenophon Armyros). Kaktos. ISBN 978-960-382-664-4.

External links

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Platon

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Platon- Works available online:

- Works by Plato in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Plato at Perseus Project – Greek & English hyperlinked text

- Works by Plato at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Plato at the Internet Archive

- Works by Plato at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Other resources:

- Plato at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project

- Plato at PhilPapers

- . Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.