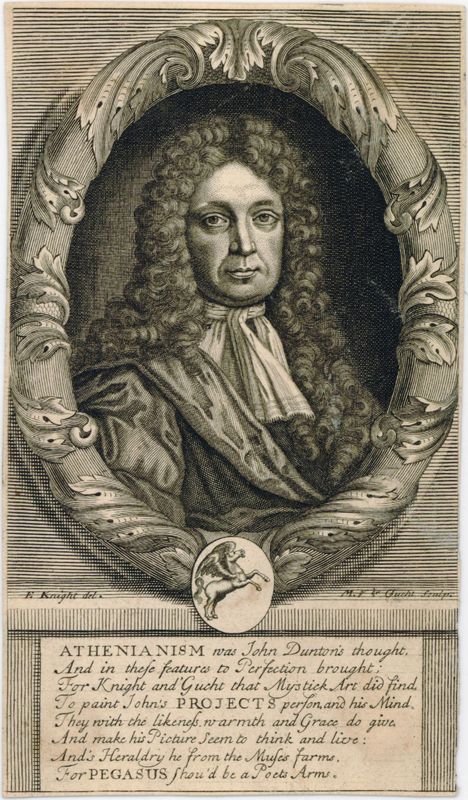

John Dunton (1659–1733)

John Dunton, bookseller, at the Raven or Black Raven in the Poultry, 1681–1694; at the Raven or Black Raven in the Poultrey over against the Stocks Market, 1683–1684; at the Black Raven at the corner of Prince's Street, near the Royal Exchange, 1684–1685; at the Raven or Black Raven in the Poultry, over against the Compter, 1689–90; at the Raven in Jewen Street, 1694–1697.

Katherine Playfair Quinsey, University of Windsor

March 2024

Introduction

John Dunton was one of the most prominent publishers of the late Restoration, and without doubt the most original. Eccentric, outspoken, and creative, he saw the book trade from two sides, both as a profitable bookseller and as a hack writer dependent for his bread. He both embodied and exploited the rapidly evolving print culture of that period, working on the cusp of changing relations between authors, booksellers, and their readership. With an unerring instinct for popular demand, in particular the thirst for knowledge and access to elite culture by people without the time or the means to read scholarly books, as well as the ever-marketable desire for personal advice on how to live, Dunton was in the forefront of producing the relatively new genres of collections, anthologies, digests, and periodicals, as well as works of practical morality and devotion. He is best known for creating a new model of reader engagement with the question-answer periodical in the club model, the Athenian Mercury (1691–1697). This pioneering project deliberately crossed boundaries of class and gender in its targeted readership and topics, using an interactive, anonymous reader-author dialogue, popularizing questions of science and philosophy as well as “advice column” questions of day-to-day life; it also provided digests and translations of works not otherwise accessible to Dunton’s readers. Specifically aimed at uneducated but literate men and women, wide-ranging and dynamic in its topics, the Athenian Mercury provided a “conduit” between elite and popular culture (Berry 147). Dunton’s practice is notable for involving women on an almost equal basis; he not only had respect for women as professionals (his first wife ran his business and ensured its success) but in the Athenian Mercury he created the first periodical aimed at women who were curious about fields of knowledge normally closed to them: science, mathematics, philosophy, and economics.

Although descended from several generations of Anglican clerical John Duntons, Dunton maintained close ties with Dissent both familial and religious as well as political. Samuel Annesley, the notable Presbyterian preacher, was his father-in-law, and Samuel Wesley, father of John and Charles, his brother-in-law and colleague. Dunton published their works, as well as numerous other pieces by Nonconformist and ejected clergy. His involvement with Whig politics and the Protestant cause is consistent through his career – from a Protestant apprentices’ petition and polemical publications of the Monmouth rebellion through to vigorous pamphleteering in Anne’s and George I’s reigns. Dunton weighed in on most major controversies, from the Exclusion crisis and Monmouth rebellion to Occasional Conformity, Sacheverell, and the Bangorian controversy, being best known for his critique of Oxford and Bolingbroke in Neck or Nothing (1713). Despite this passionate political engagement, Dunton is also distinctive in his individualistic approach and unique assessment of persons, outlined in his various memoirs.

While Dunton was one of the most eminent and successful booksellers of the early 1690s, he collapsed both personally and professionally after the death of his first wife Elizabeth Annesley Dunton, who managed his business as well as his idiosyncrasies. His later career consists largely of polemical writing with a strongly personal and confessional overflow that earned him the reputation of a lunatic crank and hack, which skewed history against his publishing accomplishments until relatively recently. He can now be seen as a pivotal figure in a transformative period in the history of English print culture and the society it helped to shape.

Dunton’s own autobiography, The Life and Errors of John Dunton (1705), is a mix of confessional memoir, individual portraits of contemporaries both male and female, and spiritual reflection in the Nonconformist tradition (on his original sin as a child, and how he would have lived better given a second chance). It forms the primary source for both John B. Nichols’s biographical introduction to the 1818 edition of Life and Errors, and for Stephen Parks’s detailed biographical account prefacing his catalogue of Dunton’s publications in John Dunton and the English Book Trade (1976).

Early Life and Career

Dunton was born 14 May 1659 to the Rev. John Dunton, third of that name and profession, rector of Graffam in Huntingdonshire, and his wife Lydia Carter of Chesham. Lydia, who had already suffered a near-mortal illness the previous year (Dunton’s account has her returning to life in her coffin), “died in earnest” (Life and Errors [1705], hereafter LE, 6) a few months after Dunton’s birth, leaving a collection of her own spiritual letters, which were later shared with Dunton by his father. This forms an early instance of the influence of strong women of faith through Dunton’s life. Dunton by his own account was a sickly infant, nearly dying at birth, possibly premature: “The first appearance which I made was very mean and contemptible [...] I was so diminutive a creature, that a q—t p—t could contain the whole of me with ease enough” (LE 6–7). His father took a position in Ireland shortly after his wife’s death, remaining there until Dunton was 9. It is an indication of Dunton’s attachment to his father that he followed up with his father’s wishes regarding a servant within that household on visiting the family in Ireland 30 years later. Dunton appears to have been fostered out with a William Reading “at Dungrove, a place almost in the neighbourhood of Chesham” (his mother’s country), where he attended elementary school once he was old enough. According to his own account, this experience begins the pattern of creative idiosyncrasy and rebelliousness which is consistent through his life: he laments that he learned so little under good instructors, both men and women. His father returned to England around 1668, remarrying and thus enabling Dunton to live at home again. Here he was home-schooled by his father in the classics and philosophy, a process again marked by Dunton’s lack of interest in strict scholarly study of the sort that would have prepared him to become the fourth clerical John Dunton. His father seems to have been affectionate and empathetic. Rather than forcing Dunton into the rigours of a classical education, he directed him to a related trade, that of publishing and bookselling, apprenticing him to the eminent Presbyterian bookseller Thomas Parkhurst. “By this means he thought to make it my interest to be at least a friend to Learning and the Muses, if I would not join myself to them by some nearer affinity […] I was now only to traffick with the outside, the shell and the casks of Learning; though, had I taken other measures, my Shop might have been a Library, and my mind the richer, and the better furnished of the two ... ” (LE 33, 34). For Dunton, the fact that he never became a cleric and did not pursue formal academic studies beyond childhood, while practicing a respectable trade, engendered a creative tension between these elements in his life and work: the intersection of aspirational academic study, spiritual and religious reflection, and entrepreneurial bookselling informed the bulk of his work and helped bring about his signature original achievement in the question-and-answer periodical The Athenian Mercury.

Although Parkhurst appears to have been, like Dunton’s father, a kindly and supportive master, according to his own account Dunton did not settle easily into the moral and professional rigours of apprenticeship, running back home during the initial trial period, later becoming romantically entangled with his master’s ward, and, in his final years of apprenticeship, falling passionately in love with fellow churchgoer Rachel Seaton. During this period, however, Dunton appears in print for the first time, in a manner reflective of his strong political and religious inclinations—his apprenticeship and entry into the book trade coinciding with a turbulent period in English politics, in the maelstrom of popular sentiment leading up to the Monmouth rebellion. In 1681 Whig apprentices organized, with him as their treasurer, presenting an aggressively Protestant petition for the opening of Parliament to the Lord Mayor as The address of above twenty thousand of the loyal Protestant apprentices of London ... in commemoration of the burning of that famous Protestant City [i.e. London] by Papists, Jesuits, and Tories, Anno 1666, printed for William Ingol the elder, 1681. The apprentices were numerous (30,000 said to have signed this petition, in contrast to the 5000 Tory apprentices with whom they were competing); as to be expected, however, the Lord Mayor’s office treated them as civic minors, thanked them for their input, and told them to go home and mind their trade and their masters. Nonetheless this pamphlet and its four following titles (a “friendly dialogue” and “vindications” and “a heroic poem”) appearing in the same year, in a time of relative risk, established Dunton’s lifelong pattern of passionate political engagement on the Whig Protestant side.

On completing his apprenticeship (hosting a “funeral” for it with all his companions, evidence of his irrepressible sociability), Dunton set up in trade by obtaining physical premises at a modest rent, including half a shop and a warehouse, and by establishing connections both with reputable authors and with fellow booksellers. “The Poultry” district, where he was established for the next fourteen years, had centuries earlier been associated with the actual poultry trade but was now a prime location for booksellers. His first substantial publication, in late 1681, was by the notable Presbyterian preacher and teacher Thomas Doolittle, entitled The Lord’s last-sufferings shewn in the Lord’s Last-Supper. Having been assisted in this initial contact by Parkhurst, Dunton followed the practice of exchange of copies with other booksellers to promote the book, while connecting with Doolittle’s students, thus expanding his trade connections and his pool of reputable writers. Dunton established himself quite quickly: within a few months he had produced four books under his own imprint and was advertising 23 others sold for him (Parks 16). By the following year (1683), he had produced a complete catalogue of 168 titles under his own logo, not to mention Bibles and “school books,” from his new premises at the sign of the Black Raven in The Poultry (Parks 23).

Black Raven frontispiece and printer’s ornament for Dunton’s The Informer’s Doom, 1683. Woodcut. Internet Archive. These images are in the public domain. |

Dunton’s early publications (1681–1685) reflect Nonconformist spirituality, Whig political sympathies, and family bonds, as well as entrepreneurial pragmatism. Stephen Jay’s Biblically-attuned praise of Anthony Ashley Cooper, first earl of Shaftesbury and icon of the Exclusion crisis, Daniel in the Den, is listed by Dunton as the second book he ever published—this in 1682, during the Monmouth movement and in Shaftesbury’s last illness. It was followed later with the virulently anti-popish The Devil’s Patriarck (“Written by an Eminent Pen [Christopher Ness, 1621–1705] to Revive the Remembrance of the almost forgotten Plot against the Life of his Sacred Majesty and the Protestant Religion”) and an anonymous poetic Elegy for Shaftesbury (1683). Dunton’s publications range widely, however: funeral sermons; practical divinity with a tendency towards allegory (Benjamin Keach’s Progress of Sin; or, the Travels of Ungodliness and Travels of True Godliness, for example); moralistic tracts anticipating the Reformation of Manners movement (Englands Vanity: or the Voice of God Against the Monstrous Sin of Pride, in Dress and Apparel: Wherein Naked Breasts and Shoulders, Antick and Fantastick Garbs, Patches, and Painting, long Perriwigs, Towers, Bulls, Shades, Curlings, and Crispings, with an Hundred more Fooleries of both Sexes, are condemned as Notoriously Unlawful, 1683); whimsical reflections (The Amazement of Future Ages: or, This Swaggering World Turn’d Up-side down, 1684); Dunton’s own Informer’s Doom, an allegorical satire on the causes of political divisiveness; and The Compleat Tradesman, a practical manual with keys to the “art” and “mystery” of the profession, suggesting an almost medieval sense of trade as a specialised skill. A significant number of publications came from his father’s study; Dunton published and reprinted these individually and collectively. One of the first was the House of Weeping, a collection of his father’s sermons and meditations for funerals; this was followed by Dunton’s Remains, a similar collection of meditations, and the Pilgrim’s Guide, an allegorized manual in the Bunyan tradition. These were collected into a volume with a loving dedication to all Dunton’s family members. Other works published independently followed this allegorical mode, including A Hue and Cry After Conscience: or, the Pilgrims Progress by Candle-light, In search after Honest and Plain-Dealing, which consists of dramatizations based on Biblical stories with lively interpolations, aimed at an uneducated readership. In collecting, re-titling, and packaging his father’s writings, Dunton appeared to see publication as both piety, public service, and profit. Finally, 1685 also saw the publication of one of the few poetic collections Dunton produced: Samuel Wesley’s whimsically titled Maggots: or Poems on Several Subjects, Never Before Handled. By a Schollar—heralding their future collaboration on the Athenian Mercury and Dunton’s lifelong use of the term “maggot” to refer to a variety of notional obsessions.

It is impossible to overemphasize the importance of his marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of Samuel Annesley and sister to Susannah Annesley, wife of Samuel Wesley and mother of the famous founders of Methodism. Elizabeth and Dunton were married 3 August 1682, after a courtship involving both family permission (with Parkhurst in loco parentis for Dunton) and companionate affection. The marriage embodied the values Dunton propounds in various works: a wife who was emotional and professional partner, intellectual equal, and friend. It is notable that Dunton and Elizabeth continued to exchange affectionate letters (as “Philaret” and “Iris”) throughout their married life, through to her final illness. They had no children. Elizabeth Dunton had all the business acumen which her husband notably lacked, as he himself attests: from the time of their marriage, “dear Iris gave an early Specimen, of her Prudence and Diligence […] and thereupon commenc’d Bookseller, Cash-keeper, managed all my Affairs for me, and left me entirely to my own Rambling and Scribling Humours. […] these were Golden-Days, Prosperity and Success were the common course of Providence with me then, and I have often thought I was blessed upon the account of Iris” (LE 100–101). Like his mother, and her own sister Susannah, she appears to have been a well-read and deeply religious woman, who kept a spiritual diary for over twenty years, some of which Dunton publishes in his Life and Errors, and some of it preached by Timothy Rogers at her funeral (The Character of a Good Woman, 1697). In the early years of their marriage Dunton travelled extensively, and through that period Elizabeth maintained the business effectively. Their different skills—his, of schmoozing, marketing, and innovating; hers, of financial and stocks management—made for business success. It was not uncommon for women to manage publishing businesses, often taking over as widows or daughters, but Elizabeth Dunton was a major factor ensuring Dunton’s business success through the political turbulence of the 1680s, and its subsequent growth and prominence into the 1690s. The sharp downturn of his fortunes following her death is notable.

Dunton’s business trip to in New England in 1685 was prompted by a number of factors: the “universal damp on Trade” (LE 101) in the political upheavals following the Monmouth rebellion, especially for writers of Dissenting sympathies (Dunton and Thomas Malthus had been briefly arrested in July 1683 on suspicion of having printed “a plot sermon” [Parks 22]); Dunton’s own connections with Monmouth sympathizers, notably his own apprentice Samuel Palmer; and his desire to expand his market based on the notion that New England with its Puritan sympathies would be fruitful territory. More generally, Dunton adored travelling, in what he called his “rambling” tendencies: meeting new people, networking, and seeing new things, seasoned by his own flair for travelogue and commentary. The journey was complicated by financial trouble: Dunton had stood surety for a sister-in-law’s debt and was briefly arrested before leaving, and a shipwreck deprived him of ₤500 worth of his stock. The voyage itself was lengthy and troublesome (four months, according to Dunton), but the stay in New England appears to have been marked by warm welcome and valuable connections. Notably, Dunton met with Cotton and Increase Mather, whose works he later published (he admired the Harvard Library and sold some books to students [LE 157]); he received a warm welcome in Boston, being given the key of the city before his departure; and he travelled further into the interior to meet the Rev. John Eliot, who lived and worked among Indigenous converts, whose life was later shaped into a publication by Cotton Mather after Eliot’s death.

Dunton’s return home in 1686 was complicated as well, owing possibly to the continuing financial difficulties of his relations, but also to the climate for Monmouth sympathizers in the early years of James II’s reign. Dunton had to go into hiding, ascribing this to his sister-in-law’s ongoing financial problems, even though Elizabeth had already paid down the debt. He provides an amusing story of going out disguised in women’s clothes to hear his father-in-law Annesley preach (LE 197–198). In this environment, Dunton travelled again, this time to Europe: primarily to Holland, a centre for publishing and a refuge for Monmouth rebels and Dissenters, where he made important connections for future publications, in particular European works for translation, “books of a forreign growth.” These included the history of the Edict of Nantes, neatly obtained in advance of other London booksellers through the friendship of “Mr. Spademan,” a Protestant clergyman in Rotterdam (LE 201). He also visited Haarlem, home of the “first inventor of PRINTING, an Art with which my Life has been so much concerned,” and, with his characteristic love of innovation, comments on the suspicion with which the new technology was first received, forcing its inventor to flee to Cologne (LE 208–209). His return coincides almost exactly with the flight of James II and the arrival of William and Mary, November 1688.

Peak Years

The years 1688–1696 saw the height of Dunton’s achievement and reputation. He started from a strong reputation and a plentiful stock of reserves, largely enabled by Elizabeth Dunton’s success in maintaining the business during his absence (see Parks 36–37). Within a year, according to his own claim, he had 30 different printers working for him – in his peak period of 1693–94 he had over 37 projects a year (Parks 41). According to Parks, although Dunton did not advertise regularly in the Term Catalogues, he listed 71 titles during the 1690s, 37 of them in 1693; Parks’s checklist brings the number up to 185, including 11 periodicals and 29 new editions of earlier works (43–44). Dunton continued to establish and expand his pool of reputable writers, partly through his existing political and religious connections and partly through the variety of genres in which he published; he utilized his international connections to publish translations, abstracts, and collections, building on connections made during his American and European stays. As a prominent figure himself, he also collaborated effectively with other booksellers, cooperative publication and exchange of copies being a protective structure that helped offset some of the insecurities of the time. Dunton had wide connections outside of London as well, "an extensive network of contacts with booksellers in Norwich, Exeter, Bristol, Worcester, Oxford and Cambridge” (Berry 22). He achieved significant social and professional stature in this period: his publications included one major work by royal license; from estates he inherited in 1692, he was able to purchase livery in the Stationers’ Company, and was invited by the Master to dine with the Lord Mayor, coming away with the treasured gift of a silver spoon for his wife.

Parks makes the important assessment that Dunton “holds his own with Curll and Dodsley, especially given the different conditions of the 1690s as opposed to the well-established market of the eighteenth century” (44). This aptly suggests the significance of Dunton’s achievement in the very different conditions of the Restoration print marketplace: political upheaval, changing distribution structures, a dynamic and growing reading public, shifts in material forms and market conditions (such as the rise of periodicals, and the shift towards smaller, portable books for general reading), all help mark the originality of some of Dunton’s concepts. McEwen in his book on the Athenian Mercury claims that by 1697 Dunton “was one of the best known and most experienced members of the London book trade. No other bookseller had advertised as widely as he during the last decade of the century […] he had weathered two periods of severe decline [in the trade], in 1685 and again in the middle years of the 1690's. […] He was on good terms with numbers of booksellers, printers, engravers, and bookbinders and took part in congers with some of the most astute among his colleagues” (209).

Dunton’s publications during this peak period range widely across genres and formats: Protestant practical divinity in sermons, tracts, and allegories; funeral sermons; doctrinal discussions between Protestant churches; Whig politics (in both newsletters and tracts); historical works; practical manuals for tradesmen and others. He achieved eminence in periodical and serial publications, digests, collections, commentaries, and, signally, advice and information periodicals in a question-answer format.

The initial years 1689–1690 predictably saw strongly polemical works in support of the Whig cause and William III’s mandate, many of them echoing back to the days of the Exclusion crisis and Monmouth rebellion, some of these reprinted and reissued in collections. In 1689 he published The Dying Speeches, Letters and Prayers, &c. Of those Eminent Protestants Who Suffered in the West of England, (And Elsewhere,) Under The Cruel Sentence Of the late Lord Chancellour, Then Lord Chief Justice JEFFERYS, as well as a collection on the same: A New Martyrology, or, The Bloody Assizes Now Exactly Methodized in One Volume ... With the Pictures of Several of the Most Eminent of Them in Copper Plates (by John Tutchin, 1661?–1701). This was reissued in a new edition with an alphabetical table in 1693. Dunton also published newsletters from the Irish front during this key year, and advertised several plays of a similar political cast.

Throughout this period, he produced a strong line of devotional works, funeral sermons, and handbooks of practical divinity in the Nonconformist vein. Of particular note is Richard Annesley’s collection Casuistical Morning-Exercises ... Preached in October, 1689: an example of case-based questions and answers in the Nonconformist tradition, which also informs the broader approach of the Athenian Mercury (see Berry 109). Also notable was the third edition of Henry Lukin’s The Practice of Godliness: or Brief Rules Directing Christians How to Keep their Hearts in a Constant Holy Frame, published in 1690. Dunton claimed to have sold 10,000 copies of this (Parks 46). The huge market for works of practical devotion and sermons should not be underestimated. John Norris’s Practical Discourses upon the Beatitudes of Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, published 1693, ran to several editions (102). Additionally, Dunton’s shop also published doctrinal debates and discussions between different Protestant denominations on church union (see for example Heads of Agreement Assented to by the United Ministers In and about London: Formerly called Presbyterian and Congregational [1691]), as well as attacks on the Quakers, who were seen as crypto-Catholic misfits, and controversies with the Anabaptists. The influence of the Reformation of Manners movement can be seen not only in their proposals published by Dunton in early 1694, but also in various tracts such as An Antidote Against Lust: Or, a Discourse of Uncleanness, by Robert Carr, Minister of the Church of England (1690). A strong element of Calvinism appears in the variety of tracts aimed at educating and converting youth, such as The Vanity of Childhood & Youth, Wherein the Depraved Nature of Young People is Represented, and Means for their Reformation Proposed, by Daniel Williams (1691).

The relationships forged during Dunton’s travels helped expand both print marketplace and readers’ expectations beyond British confines. He produced reprints of works by Cotton Mather originally published in Boston, not only his famous accounts of the Salem witch trials (1693), but also Mather’s account of the life and ministry of John Eliot amongst the Indigenous North Americans (1694). Dunton’s European travels led to the multi-volume translation of Elie Benoit’s History of the Famous Edict of Nantes, for which Queen Mary gave her “trusty and well-beloved John Dunton, Citizen and Stationer of London” her “Royal Licence for the sole Printing and Publishing thereof.” Only the first two volumes eventually appeared in print, but it shows Dunton at the forefront of publishing European works for a middle-class Protestant English readership.

Dunton’s accurate sense of his reading public, and his understanding of his own vocation—combining principle with profit—lay behind his distinctive focus on education, information, abstracts, digests, and handbooks for a knowledge-thirsty readership. Dunton was never one to step back from a large project, and these works crossed a wide range of fields, as either multi-volume textbooks popularizing scientific, philosophical, and mathematical concepts, or as periodicals with a similar purpose. William Leybourne’s mathematics textbook with wide-ranging applications (Pleasure with Profit Consisting of Recreations of Divers Kinds, viz., Numerical, Geometrical, Mechanical, Statical, Astronomical, Horometrical, Cryptographical, Magnetical, Automatical, Chymical, and Historical) was published in 1694 together with Richard Sault’s treatise on algebra. Large scope treatises include William Turner’s The History of All Religions in the World: From the Creation down to this Present Time. Burthogge’s Essay on Reason (1694) is a reminder that Dunton was associated with John Norris and a supporter of Locke. One notable and innovative success, which was adapted until well into the nineteenth century was Leybourn’s Panarithmologia, Being a Mirror, Breviate, Treasure, Mate, for Merchants, Bankers, Tradesmen, Mechanicks, and a Sure Guide for Purchasers, Sellers, or Mortgagers of Land, Leases, Annuities, Rents, Pensions ... (1693). According to Parks, this was “described by C.E. Kenney as the first instance of ‘the large ready reckoner as we know it today’ and ‘the most enduring of all Leybourn’s works’ (Parks 56, 412n54).

Collections, abstracts, and digests, a form already relied on for church ministry, were gaining more general popularity, and formed a consistent element of Dunton’s output. Flores Intellectuales: or, Select Notions, Sentences and Observations, ... especially for the Use of young Scholars, entring into the Ministry, by Matthew Barker, was published in two volumes 1691–1692. Dunton’s favoured format for such material, however, was the periodical, either in a weekly or monthly format, or collected into volumes, most of which he published and/or proposed in the early 1690s. Many of these informational works and digests were based on European sources. In summer of 1694 Dunton published Jean-Baptiste de Chèvremont’s The Knowledge of the World, or, The Art of Well-educating Youth, based on translations of the French Monthly Letters on Education (Parks 70). As advertised in the early issues of the Athenian Mercury, in which he proposed to publish their English translations, Dunton clearly saw his “Athenian” work as a popular analogue to the numerous scholarly journals of abstracts available across Europe, such as Paris’s Journal des Savans, Leipzig’s Acta Eruditorum, Amsterdam’s Biblioteque Universell, and Rome’s Giornall de' Litterati, not to mention England’s Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society—and provision of public access as the journal’s central purpose:

That nothing might be wanting to render our Athenian Project serviceable to the Publick, and throughly known, we shall again give an Account of what we design’d from our very first engageing in it-----which was not only to confine our selves to Answer all manner of Theological and other Questions whatever that shall be sent us […] but also to give Accounts of most Books transmitted to us from Forreign parts, in Order whereto we have settled a Correspondence beyond Sea being resolved to spare no Charges to gratifie the Ingenious.

We design also to insert the Transactions and Experiments of several English Virtuoso's, and what ever else is CURIOUS that shall be sent us from time to time, and to transcribe (that so we may the more fully make good our Title) from the Acta Eruditorum Lipsae, the Paris Journal des Scavans, the Giornali de Litterati, Printed at Rome and the Universal Historical Bibliotheque, &c., all that we conceive will be lookt upon as valuable---------ALL which we intend to add (together with our Answers to Objections) at the end of every Volume, they being Licensed and Enter’d, and now Translating in order to it. (Athenian Mercury 1.12 (21 May 1691), p. 2).

These collections were published separately. In 1692 Dunton published The Young-Students-Library. Containing, Extracts and Abridgments of the Most Valuable Books Printed in England, and in the Forreign Journals, by the Athenian Society (1692). The Compleat Library, a succeeding collection, has an interesting history across both national and elite lines: it crossed paths with the Bibliotheque Generale of Jean LeClerc through his assistant Jean LaCrose, who was producing an English language digest of collections and abstracts based on it entitled The Works of the Learned. After a brief and rather nasty tussle, Dunton and his associate Thomas Bennet arranged to publish La Crose’s journal; it was eventually continued in Dunton’s The Compleat Library, published monthly May 1692–June 1694.

Another offshoot of the Athenian Mercury was the Ladies Dictionary (1694), which does not consist of the antifeminist or courtly stereotypes that might be expected but is more like a dictionary of female names and their sources in history, with a wide array of historical and mythological persons and types. Another related project from this year was The Night-Walker; Or, Evening Rambles in Search after Lewd Women, which was ostensibly an on-the-ground moral project to expose the well-recognized social problem of prostitution, but which predictably, had overtones of prurience. Dunton’s gift for journalism is evident in another of his periodicals, Pegasus, with News, an Observator, and a Jacobite Courant (issued three times weekly, 15 June–11/14 September 1696), which Parks sees as the most notable of Dunton’s projects outside the Athenian Mercury, citing Walter Graham, who described Pegasus as “the first really good example of a newspaper with features” (Parks 71, 414n77; Graham 376).

In addition to writing for some of his own periodicals, Dunton also wrote some independent pieces. His flair for travel writing and autobiography appears in the persona of Kainophilus in A Voyage Round the World (1691), which apparently influenced Sterne’s Tristram Shandy in its whimsicality (Parks 50–51). Other works of Dunton’s reflect his passionate Whig stance: England’s Alarum: Being an Account of God's Most Considerable Dispensations of Mercy and Judgment towards these Kingdoms for Fourteen Years last past, printed for Parkhurst in 1693, and the periodical The True Protestant Mercury, or an Impartial History of the Times, which ran weekly for 10 weeks December 1689–February 1690 (Parks 69). Visions of the Soul, Before It Comes Into the Body. In Several Dialogues, (1692), which arises from questions posed to the Athenian Mercury, is a satire on heterodox beliefs about the soul’s pre-existence.

Dunton seems to have subscribed to what today we would call the conventional bourgeois view that poetry led necessarily to poverty: “But, alas! after all, when I see an Ingenious Man set up for a meer Poet, and steer his Course through Life towards that Point of the Compass, I give him up, as one pricked down by Fate for misery and misfortune” (LE 243). Despite these comments, he published a number of poems and collections, Wesley’s Maggots, Richard Baxter’s Poetical Fragments, and the “Pindarick Lady” Elizabeth Singer’s Poems on Several Occasions (1696) being the most famous. For that matter, Dunton occasionally committed poetry himself. But there is no doubt that his primary interest lay in non-fiction prose generated for and by his readership.

Athenian Mercury

Dunton’s low opinion of hack writers, whose “great concern lay more in how much a Sheet , than in any generous respect they bore to the Commonwealth of Learning” (LE 70) and his emphasis on gathering a pool of respectable writers, and on the academic quality and public service of his publications, reflect his precise sense of the changing book market: the appetite of the uneducated or semi-educated literate reader, “middling” sorts (Berry 72–73) ranging from professionals to tradespeople to those in service, for knowledge and improvement, spiritual and moral information and advice, and access to reliable information and elite knowledge. The Athenian Mercury was the most innovative and most influential expression of this, appearing in both twice weekly single sheet format and in bound collections.

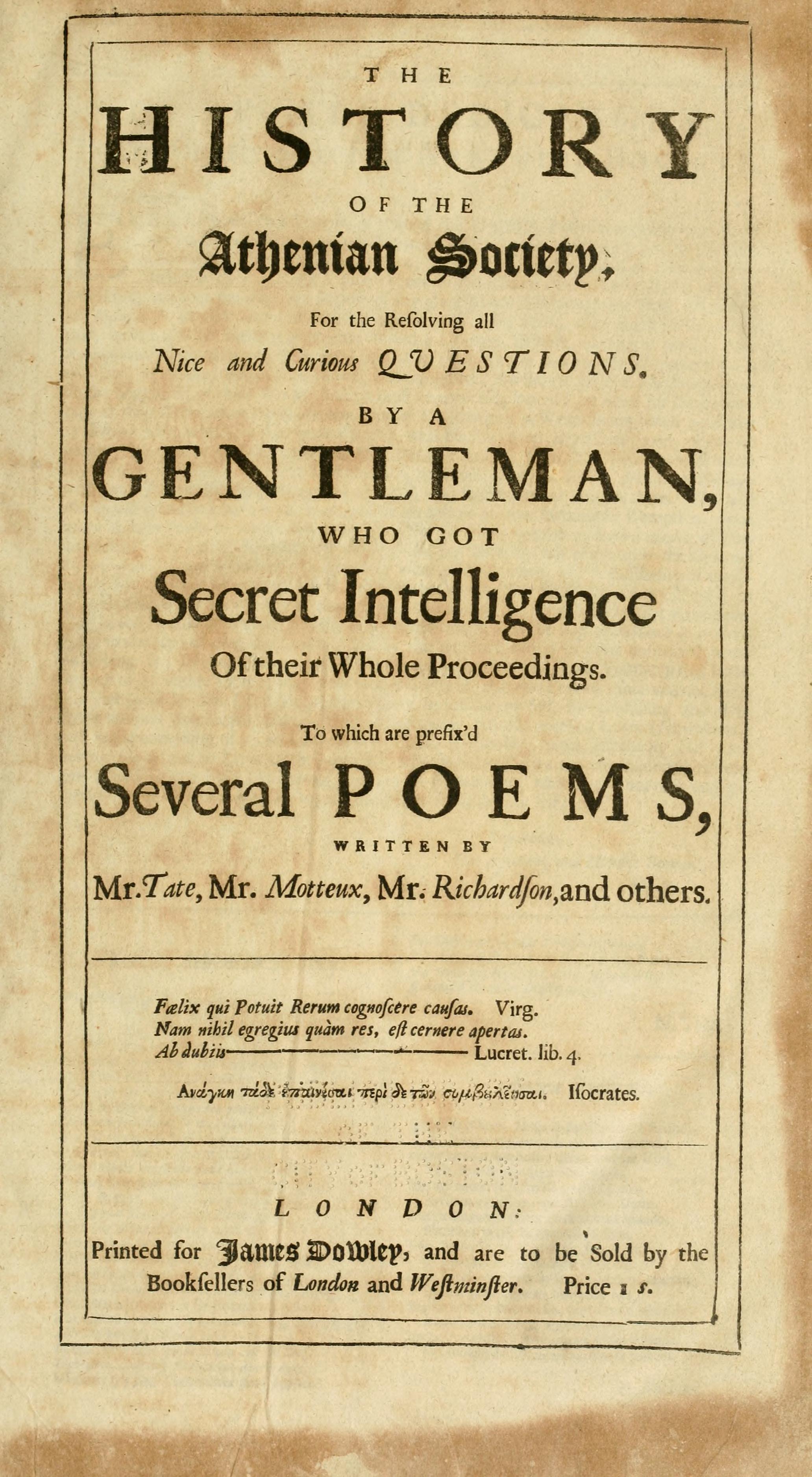

Engraved portrait of the Athenian Society and their readership, frontispiece to Charles Gildon’s History of the Athenian Society (London: James Dowley, 1692). Boston Public Library Rare Book Department. These images are in the public domain. |

The Mercury was Dunton’s signature achievement. It was the longest-running periodical of the time, from 17 March 1691 to 14 June 1697, exceeded only by the staid state journal The London Gazette. In our own era there have been two full monographs devoted to the Athenian Mercury and its readership and significance in society. The Mercury was original first of all in its format: questions on any topic sent in from anonymous individual readers, answered by a quasi-fictional entity with access to authoritative information and learning. Dunton chose the name “Athenian Society” as a gesture not only to classical learning but also to the Biblical representation of the Athenians as questioning philosophers and welcomers of new ideas. Dunton claimed that this idea (of the anonymous question-answer format) came to him out of the blue as the child of his own brain, and he jealously guarded the concept as his intellectual property, though it naturally generated imitations. The Mercury was also distinctive in that it specifically targeted a readership not normally invited to the discourses of learning: women, tradespeople, servants, any literate but not necessarily educated person. “The Design is briefly, to satisfy all ingenious and curious Enquirers into Speculations, Divine, Moral and Natural, &c. and to remove those Difficulties and Dissatisfactions, that shame or the fear of appearing ridiculous by asking Questions, may cause several Persons to labour under, who now have opportunities of being resolv’d in any Question without knowing their Informer” (Athenian Mercury 1.1, 17 March 1691, qtd. in McEwen 23). This opened the floodgates to a host of questions ranging across topics both scientific, philosophical, social, and personal, from a social majority eager to learn. This feature of the Mercury was so marked that it drew scornful criticism from some rivals, particularly of its focus on women readers. Women were so prominent in the responses to the Mercury that Dunton published one issue a month specifically devoted to women’s questions.

The Athenians themselves consisted initially of Dunton and his mathematical brother-in-law Richard Sault; they were joined soon after by another brother-in-law, Samuel Wesley. They were later assisted by Dr. John Norris, philosopher, divine, and correspondent of Mary Astell. Answers were divided between them according to their expertise and interest. While the “Athenian Society” maintained a more amorphous fictional identity (of possibly twelve experts), the writers were generally known, and the publisher, certainly. The periodical was entered 17 March 1691 as The Athenian Gazette, Resolving Weekly All the Most Nice and Curious Questions Proposed by the Ingenious (Parks 80); after the first issue, it was “obliged by authority” to change its title to Athenian Mercury (possibly to avoid confusion with the London Gazette). Not only did the change in title work to their advantage in calling readers’ attention to them in the print marketplace, it provided them with the opportunity to explain in print the difference in linguistic meaning between a “gazette” and a “mercury,” and so to highlight the availability of their journal in both the serial “mercury” and the monthly collected “gazette” (Athenian Mercury 1.12, 21 May 1691, p. 1, question 1). The Mercury was a runaway success: by the second week they increased publication to twice weekly, requesting that questioners hold off until they had answered all the questions received. It was published in a single sheet, and distributed widely, to coffee houses and to Dunton’s array of bookselling connections in the country, as well as through his “Mercury women” selling copies individually in the streets. Early on Dunton started collecting the twice-weekly issues into bound volumes; moreover, he would publish only the first 18 numbers of a 30-number group in the sheet format, keeping the remaining 12 as additional “supplements” largely written or organized by himself. Thus, Dunton combined the form of the traditional bound academic book in its permanence and authority with the ephemeral, responsive, and interactive nature of the periodical.

This real-time interactivity with the readership highlights the Mercury’s difference from its eighteenth-century descendants, such as the fictitious gentlemen’s club of the Spectator. Questions were received from a wide range of readers, both educated and uneducated, professional and lower-class, male and female. While some questions appear to be potted, it is clear that for the most part the Society had an active relationship with real readers: they requested that postage be paid; there was an active backlog of questions, and readers were asked to refrain from repeat enquiries; finally, and tellingly, they dealt crisply with trolling questions from educated men who were trying to mock them or catch them out. Questions ranging from the laws of marriage to those of physics to those of the Bible were answered with a review of current and historical positions on the subject, followed by the Society’s overall conclusion, or summary, if possible. The general effect is not unlike modern scholarship, but specifically aimed at a wide readership.

The Mercury lives up to its title: it compliments its unlearned readers on their inquisitiveness and intelligence (as “ingenious” or “curious”) and it bases much of its methodology on casuistry, a form of empiricism, but originally religious in nature: the case-based analysis of social, religious, physical, philosophical, and personal problems (see Berry, ch. 5). It is refreshing in its juxtaposition of abstruse scientific and philosophical questions with the personal questions about relationships that we might associate with an advice column. The “Athenian Society” evokes an elite organization of high scholarly authority while at the same time the journal makes clear that its members are professionals under paid contract, “obliged” to produce every Tuesday and Saturday. Finally, the Mercury was also deliberately conceived as a “conduit” between the elite culture represented by the Royal Society and the popular culture of Dunton’s readers (Berry 88–89, 147). As stated in the introduction to Charles Gildon’s History of the Athenian Society (1692, published by James Dowley, but commissioned by Dunton), “England has the Glory of giving Rise to two of the noblest Designs that the Wit of Man is capable of inventing, and they are, the Royal Society, for the experimental improvement of Natural Knowledge, and the Athenian Society for communicating not only that, but all other Sciences to all men, as well as to both Sexes; and the last will, I question not, be imitated, as well as the first, by other Nations" (History 3, qtd. in Parks 100).

Later Years

The lapse of the Licensing Act in 1695 had a significant effect on the book trade, as competition greatly increased. Not only this changing market but also Dunton’s personal situation led to a decline in his publications and to the eventual closing of the Athenian Mercury after its record run. His business fell apart dramatically after the lengthy illness and eventual death of Elizabeth in May 1697; Dunton lacked her financial and management skills and was deeply demoralized, to the extent of purchasing his own coffin the day after his wife’s death (Berry 24). Worse, disobeying the advice of friends and that of his own Athenian Mercury, he married Sarah Nichols within months of Elizabeth’s death, with hopes of financial assistance from her mother in exchange for a jointure involving some of his own estates. The arrangement was disastrous on all accounts. The Duntons lived separately for most of their married life (Dunton with the excuse that an heir would complicate their jointure agreement) and relations with his mother-in-law soured very early in the marriage, together with any hope of financial agreement. This was not assisted by Dunton’s habit of publishing detailed accounts of his marital and financial difficulties, often with provocative dedications, in a manner not unlike those who overshare on social media today. Quite simply, he was a compulsive and inveterate spammer. A sampling includes The Dublin Scuffle (1699); An Essay, Proving We shall know our Friends in Heaven (1699); The Case of John Dunton, Citizen, with Respect to his Mother-in-Law, Madam Jane Nicholas, of St. Albans; and her only Child, Sarah Dunton, With the Just Reasons for Her Husband’s Leaving Her (1700); The Art of Living Incognito [letters on the same] (1700); Reflections on Mr. Dunton’s Leaving His Wife (1700); and, more hopefully, The Case is Alter’d: Or, Dunton’s Re-marriage to the Same Wife (which set out the conditions for their reunion). Most of these were published by his friend Anne Baldwin (see also Parks 150–151). Another idiosyncratic publication, Dunton’s Whipping-Post: Or, A Satyr on Everybody (1706) exercises his liking for character sketch in both panegyric and satiric portraits of contemporaries.

He travelled over water one more time, in a trip to Ireland in 1698. In addition to temporarily escaping his personal problems, this trip also arose from a stated desire to rid himself of the care of a shop (a task done by his first wife) and replace it with a warehousing and auction model, which he appears to have practised with some success while there; it also pandered to his desire for sociability, networking, and travel. As in his New England trip, he made friends of both sexes and professional connections across all levels of the trade and society. His account of this journey in The Dublin Scuffle tends to overplay confrontation (in this case, a quarrel over auction space) but it also provides a valuable account of those involved in the trade in Ireland at the time and of various personalities both male and female.

Dunton’s later professional activity consists of writing and pamphleteering rather than publishing, earning him the reputation for lunacy as a result of his innate pugnacity and impulsiveness. Attempts to revive the “question-project” of the Athenian Mercury, a concept he possessively clung to as to a patent, met with some success: he sold the rights to the Mercury to Andrew Bell in 1703 and it was published for some years under the title The Athenian Oracle. Clearly the model still held appeal for readers, but Dunton lacked the collegial committee to provide the materials and the momentum, as well as the means and the health to pursue it consistently. Moreover, the various offshoots he published in 1704 (The Athenian Spy, a collection of letters from the Mercury’s women readers; Athenae Redivivae, a monthly; The Athenian Catechism—published specifically for “the poorer sort” at a penny)—did not succeed. Neither did later variations on that theme (Athenianism, 1710, a proposal to publish his collected works, which he counts at 600 original pieces, though only 24 actually appear; and a similarly comprehensive Athenian Library in 1725). Nonetheless, in the first decade of the eighteenth century Dunton produced by his own hand not only these Athenian revivals but also newer concept journals such as the Post-Angel (1701); supposedly dictated by an angelic messenger, this included not only answers to questions but also book reviews, biographies, and notes on special “providences” of each month, “with a Spiritual Observator upon each Head.” It testifies to Dunton’s ongoing creative energy and his commitment to this medium. Also of interest is Petticoat-government. In a Letter to the Court Ladies (1701), which, like the Ladies Dictionary, does not demean women but conversely argues in favour of their equal abilities, in language reminiscent of Mary Astell.

Dunton continued to be notable for political pamphleteering—there seems to have been no Church-State controversy in which he did not get himself involved, for both principle and profit—but he is best known for his 1713 response to Robert Walpole’s Short History of the Parliament in the same year and published by the same bookseller (Thomas Warner), a critique of Bolingbroke and Oxford entitled Neck or Nothing, its title a flippant nod to the possible penalties for satirizing prominent officials of the government. Subsequent pamphlets in support of Hanoverian succession and George I are followed rather pathetically by tracts pleading for some recognition and support from the government for his polemics in their behalf, notably Mordecai’s Memorial: Or, There’s Nothing Done for Him. Being a Satyr upon Some-body, but I name No-body (1716) and Mordecai’s Dying Groans from the Fleet Prison (1717), reprinted in 1719 with an edition of Neck or Nothing, and again in 1723.

In these later years Dunton suffered significant financial difficulty as well as health challenges in a painful kidney condition, living with friends and landladies on whom he was dependent for medical care, in and out of the Fleet prison and in the shadow of “attachers” seizing his assets. His works were published by a consortium of booksellers, which eventually dwindled to one member, Sarah Popping. Many of his later publications are lengthy screeds to creditors and the public, rehearsing his personal woes; the autobiographical and reflective tendencies of Life and Errors (1705) spilling into rampant confessionalism and reactivity evocative (as is much of the print culture of the time) of the early days of the internet; even the very title pages of some of his later works (see for example Dying Groans, 1723) contain a mini-narrative of his wrongs.

Dunton was only 38 when Elizabeth died and his fortunes turned. The latter half of his career impressed historical memory with the reputation of an irascible eccentric writer who could be grouped with the hacks whom he had formerly despised, and who was mocked by his previous colleagues in the trade. It is only in recent years that John Dunton has been recognized as a prominent publisher who made a lasting and original contribution to print culture and readership in the pivotal and dynamic period of the late Restoration. Dunton’s work has helped reshape current understanding of both the nature of the print trade and the who, what, and where of English readership at a time of radical change.

Resources

Berry, Helen. Gender, Society and Print Culture in Late-Stuart England: The Cultural World of the Athenian Mercury. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003.

Berry, Helen. “John Dunton (1659–1733).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/8299

Dunton, John. The life and errors of John Dunton Late Citizen of London; Written by Himself in Solitude. With an Idea of a New Life; Wherein is Shewn How He'd Think, Speak, and Act, Might he Live Over his Days Again: Intermix'd with the New Discoveries The Author has Made In his Travels Abroad, And in his Private Conversation at Home. Together with the Lives and Characters of a Thousand Persons now Living in London, &c. Digested into Seven Stages, with their Respective Ideas. London: For S. Malthus, 1705. Eighteenth-Century Collections Online.

Graham, Walter. English Literary Periodicals (New York, 1930).

Kenney, C.E. “William Leybourne, 1626–1716.” The Library, 5th series, V (1950), pp. 159–171.

McEwen, Gilbert D. The Oracle of the Coffee House: John Dunton’s Athenian Mercury. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1972.

Nichols, John Bowyer, ed. The Life and Errors of John Dunton, Citizen of London; With the Lives and Characters of More than a Thousand Contemporary Divines, and Other Persons of Literary Eminence. To Which are Added, Dunton’s Conversation in Ireland; Selections from his Genuine Works; and a Faithful Portrait of the Author. London: J. Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1818.

Parks, Stephen. John Dunton and the English Book Trade: A Study of his Career with a Checklist of His Publications. New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1976.

A Dictionary of the Printers and Booksellers who were at Work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1668 to 1725, by Henry Plomer (1922)

DUNTON (JOHN), bookseller in London, (a) Raven, (b) Black Raven; (1) in the Poultry, (a) at the corner of Prince's Street, near the Royal Exchange, (b) over against the Stocks Market; (2) in the Poultry, over against the Compter; (3) in Jewen Street. 1674–1700 (?). Born at Grassham, Huntingdon, May 4th, 1659, son of the Rev. John Dunton, he was at first intended for the Church, but disappointing his father's expectations was apprenticed in about 1674 to Thomas Parkhurst the bookseller. During his apprenticeship he headed an address of the Whig prentices against one of the Tories, and he seems to have been already somewhat volatile in conduct. After the expiration of his term he set up as a bookseller, at first taking only half a shop. He took to "printing", i.e. publishing, at once; his first books being Thomas Doolittle's The Lord's Last Sufferings, 1681 [T.C. I. 458], and Stephen Jay's Daniel in the Den, a sermon by John Shower, and a collection of his father's funeral sermons, entitled The House of Weeping, with a memoir by himself. He made a success with his publications, and opened a shop at the Black Raven, at the corner of Prince's Street, where in 1685 he published Maggots, being the anonymous juvenile poems of Samuel Wesley, father of John and Charles. Dunton had in 1682 married Elizabeth, daughter of Dr. Samuel Annesley, a leading Nonconformist preacher. In 1685 his business received a check by the "universal damp upon trade, occasioned by the defeat of Monmouth in the West"; he went to Boston in New England to sell a cargo of books and at the same time recover debts to the extent of £500 owed him there, his business being largely in Puritan theology. Here he visited Elliot, who presented him with twelve copies of his Indian Bible. Dunton returned in 1686, but having given surety for £1,200 for a brother-in-law, was compelled to seek refuge in a tour in Holland and Germany. He returned in 1688 and opened a new shop opposite the Poultry Compter, with the old sign of the Black Raven, and tells us that he remained there ten years "with variety of successes and disappointments." [Life and Errors, pp. 151–2.] But his last entry in the Term Catalogues from this house was in 1694, after which he only made one more entry, in 1696, from the Black Raven, Jewen Street. After 1688 Dunton published copiously, some of his ventures being "projects" of his own, noteworthy among these being the Athenian Gazette, 1689–95, The Post-Boy Robbed of His Mail (a collection of letters), and a laudatory life of Judge Jeffreys. In the course of his career Dunton claims to have printed 600 books (employing a large variety of printers), and to repent of but seven. In 1692 he attained the Livery of the Stationers' Company. His first wife died in 1697; in the same year he married Sarah Nicholas of St. Albans, with whom [he?] and her mother he quarrelled over the non-payment of his debts. Soon after his second marriage he visited Dublin with a cargo of books, and became engaged in a quarrel with a bookseller there, Patrick Campbell (q.v.), which he set forth at length with much else in his Dublin Scuffle, 1699. Dunton was now compelled to hide from his creditors and so to give up his business; he employed his enforced leisure in much writing, in which growing insanity clearly appears. But in 1703 he wrote The Life and Errors of John Dunton (S. Malthus, 1705), in which he gives not only his autobiography, but characters of a vast number of his contemporaries in the book trade, which have been of the greatest value in the compilation of this Dictionary. After this he fell further into poverty. In the notes to the Dunciad Pope calls him "a broken bookseller and abusive scribbler". He lived till 1733. [Life and Errors, ed, with memoir by J.B. Nichols, 1817; D.N.B.]

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

DUNTON, JOHN (1659–1733), bookseller, was born 4 May 1659. His father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all named John Dunton, and had all been clergymen. His father had been fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and at the time of his birth was rector of Graffham, Huntingdonshire. His mother, Lydia Carter, died soon after his birth, and was buried in Graffham Church 3 March 1660. His father retired in despondency to Ireland, where he spent some years as chaplain to Sir Henry Ingoldsby. About 1668 he returned, and became rector of Aston Clinton, Buckinghamshire. The son had been left in England, and sent to school at Dungrove, near Chesham. He was now taken home to his father's, who educated him with a view to making him the fourth clergyman of the line. Dunton, however, was a flighty youth. He fell in love in his thirteenth year; he declined to learn languages, and, though he consented to ‘dabble in philosophy,’ confesses that his ethical studies affected his theories more than his practice. At the age of fourteen he was therefore apprenticed to Thomas Parkhurst, a bookseller in London. He ran away once, but on being sent back to his master's he became diligent, and learnt to ‘love books.’ His father died 24 Nov. 1676. During the remainder of his apprenticeship he was distracted by love and politics. He helped to get up a petition from five thousand whig apprentices, and gave a feast to a hundred of his fellows to celebrate the ‘funeral’ of his apprenticeship. He started in business by taking half a shop, and made his first acquaintance with ‘Hackney authors,’ of whose unscrupulous attempts to impose upon booksellers he speaks with much virtuous indignation. He was, however, lucky in his first speculations. He printed Doolittle's ‘Sufferings of Christ,’ Jay's ‘Daniel in the Den’ (Daniel being Lord Shaftesbury, who had been just released by the grand jury's ‘ignoramus’), and a sermon by John Shower. All these had large sales, which gave him an ‘ungovernable itch’ for similar speculations. He looked about for a wife, and after various flirtations married (3 Aug. 1682) Elizabeth, daughter of Samuel Annesley [q. v.] Samuel Wesley, father of John, married Ann, another daughter, and it has been supposed that Defoe married a third. Dunton and his wife called each other Philaret and Iris. They settled at the Black Raven in Prince's Street, and prospered until a depression in trade caused by Monmouth's insurrection in 1685. Dunton then resolved to make a voyage to New England, where 500l. was owing to him, and where he hoped to dispose of some of his stock of books. He had become security for the debt of a brother and sister-in-law, amounting to about 1,200l., which caused him much trouble. He sailed from Gravesend in October 1685, and reached Boston after a four months' voyage. He sold his books, visited Cambridge, Roxbury, where he saw Elliot, the ‘apostle of the Indians,’ learnt something of Indian customs, stayed for a time at Salem and Wenham, and after various adventures returned to England in the autumn of 1686. He was now in danger from his sister-in-law's creditors; he had to keep within doors for ten months, and growing tired of confinement he rambled through Holland, and then to Cologne and Mayence, returning to London 15 Nov. 1688. Having somehow settled with his creditors, he opened a shop with the sign of the Black Raven, ‘opposite to the Poultry compter,’ and for ten years carried on business as a bookseller. He published many books and for a time prospered. In 1692 he inherited an estate on the death of a cousin, and became a freeman of the Stationers' Company. He states that he published six hundred books and only repented of seven, which he advises the reader to burn. The worst case was the ‘Second Spira,’ a book written or ‘methodised’ by a Richard Sault, of whom he gives a curious account. As he sold thirty thousand copies of this in six weeks, he had some consolation. His most remarkable performances were certain ‘projects.’ The chief of these was the ‘Athenian Gazette,’ afterwards the ‘Athenian Mercury,’ published weekly from 17 March 1689–90 to 8 Feb. 1695–6. This was designed as a kind of ‘Notes and Queries.’ He carried it on with the help of Richard Sault and Samuel Wesley, with occasional assistance from John Norris. An original agreement between Dunton, Wesley, and Sault for writing this paper (dated 10 April 1691) is in the Rawlinson MSS. in the Bodleian. Gildon wrote a ‘History of the Athenian Society,’ with poems by Defoe, Tate, and others prefaced. Sir William Temple was a correspondent, and Swift, then in Temple's family, sent them in February 1691–2 the ode (prefixed to their fifth supplement), which caused Dryden to declare that he would never be a poet. A selection called ‘The Athenian Oracle’ was afterwards published in three volumes; and Dunton tried to carry out various supplementary projects. Dunton's wife died 28 May 1697. She left a pathetic letter to her husband (printed in Life and Errors), and he speaks of her with genuine affection. The same year he married Sarah (whom he always calls ‘Valeria’), daughter of Jane Nicholas of St. Albans. The mother, who died in 1708, was a woman of property, who left some money to the poor of St. Albans. She quarrelled with Dunton, who separated from his wife and makes many complaints of his mother-in-law for not paying his debts. He had left his wife soon after their marriage on an expedition to Ireland. He reached Dublin in April 1698 (ib. 549), sold his books in Dublin by auction, and got into disputes with a bookseller named Patrick Campbell. A discursive account of these and of his rambles in Ireland was published by him in 1699 as ‘The Dublin Scuffle.’ He argues (ib. 527) that ‘absence endears a wife;’ but it would seem from the ‘Case of John Dunton with respect to Madam Jane Nicholas of St. Albans, his mother-in-law,’ 1700, that the plan did not answer on this occasion. His wife wrote to him (28 Feb. 1701) in reference to the ‘Case,’ saying that he had married her for money and only bantered her and her mother by ‘his maggoty printers’ (ib. p. xix). Dunton's difficulties increased; his flightiness became actual derangement (ib. 740); and his later writings are full of unintelligible references to hopeless entanglements. He published his curious ‘Life and Errors of John Dunton, late citizen of London, written in solitude,’ in 1705. He states (ib. 240) that he is learning the art of living incognito, and that his income would not support him, ‘could he not stoop so low as to turn author,’ which, however, he thinks was ‘what he was born to.’ He is now a ‘willing and everlasting drudge to the quill.’ In 1706 he published ‘Dunton's Whipping-post, or a Satire upon Everybody …’ to which is added ‘The Living Elegy, or Dunton's Letter to his few Creditors.’ He declares in it that his property is worth 10,000l., and that he will pay all his debts on 10 Oct. 1708. In 1710 appeared ‘Athenianism, or the New Projects of John Dunton,’ a queer collection of miscellaneous articles. He took to writing political pamphlets on the whig side, one of which, called ‘Neck or Nothing,’ attacking Oxford and Bolingbroke, went through several editions, and is noticed with ironical praise in Swift's ‘Public Spirit of the Whigs.’ In 1717 he made an agreement with Defoe to publish a weekly paper, to be called ‘The Hanover Spy.’ He tried to obtain recognition of the services which he had rendered to the whig cause and to mankind at large. In 1716 he published ‘Mordecai's Memorial, or There is nothing done for him,’ in which an ‘unknown and disinterested clergyman’ complains that Dunton is neglected while Steele, Hoadly, and others are preferred; and in 1723 an ‘Appeal’ to George I, in which his services are recounted and a list is given of forty of his political tracts, beginning with ‘Neck or Nothing.’ Nothing came of these appeals. His wife died at St. Albans in March 1720–1, and he died ‘in obscurity’ in 1733. Dunton's ‘Life and Errors’ is a curious book, containing some genuine autobiography of much interest as illustrating the history of the literary trade at the period; and giving also a great number of characters of booksellers, auctioneers, printers, engravers, customers, and of authors of all degrees, from divines to the writers of newspapers. It was republished in 1818, edited by J. B. Nichols, with copious selections from his other works, some of them of similar character, and an ‘analysis’ of his manuscripts in Rawlinson's collections in the Bodleian. His portrait by Knight, engraved by Van der Gucht, is prefixed to ‘Athenianism’ and reproduced in ‘Life and Errors,’ 1818.

Dunton's works are: 1. ‘The Athenian Gazette’ (1690–6) (see above). 2. ‘The Dublin Scuffle; a Challenge sent by John Dunton, citizen of London, to Patrick Campbell, bookseller in Dublin … to which is added some account of his conversation in Ireland …’ 1699. 3. ‘The Case of John Dunton,’ &c., 1700 (see above). 4. The ‘Life and Errors of John Dunton,’ 1705 (see above). 5. ‘Dunton's Whipping-post, or a Satire upon Everybody. With a panegyrick on the most deserving gentlemen and ladies in the three kingdoms. To which is added the Living Elegy, or Dunton's Letter to his few Creditors. … Also, the secret history of the weekly writers …’ 1706. 6. ‘The Danger of Living in a known Sin … fairly argued from the remorse of W[illiam] D[uke] of D[evonshire],’ 1708. 7. ‘The Preaching Weathercock, written by John Dunton against William Richardson, once a dissenting preacher,’ n. d. 8. ‘Athenianism, or the New Projects of Mr. John Dunton … being six hundred distinct treatises in prose and verse, written with his own hand; and is an entire collection of all his writings. … To which is added Dunton's Farewell to Printing …. with the author's effigies …’ 1710. The ‘Farewell to Printing’ never appeared; only twenty-four of the ‘six hundred projects’ are given; a list is given of thirty-five more, which are to form a second volume, never issued. One of them, ‘Dunton's Creed, or the Religion of a Bookseller,’ had been published in 1694 as the work of Benjamin Bridgewater, one of his ‘Hackney authors.’ 9. ‘A Cat may look at a Queen, or a Satire upon her present Majesty,’ n. d. 10. ‘Neck or Nothing.’ 11. ‘Mordecai's Memorial, or There is nothing done for him; a just representation of unrewarded services,’ 1716. 12. ‘An Appeal to His Majesty,’ with a list of his political pamphlets, 1723. The short titles of these are: (1) ‘Neck or Nothing,’ (2) ‘Queen's Robin,’ (3) ‘The Shortest Way with the King,’ (4) ‘The Impeachment,’ (5) ‘Whig Loyalty,’ (6) ‘The Golden Age,’ (7) ‘The Model,’ (8) ‘Dunton's Ghost,’ (9) ‘The Hereditary Bastard,’ (10) ‘Ox[ford] and Bull[ingbroke],’ (11) ‘King Abigail,’ (12) ‘Bungay, or the false brother (Sacheverell) proved his own executioner,’ (13) ‘Frank Scamony’ (an attack upon Atterbury), (14) ‘Seeing's Believing,’ (15) ‘The High-church Gudgeons,’ (16) ‘The Devil's Martyrs,’ (17) ‘Royal Gratitude’ (occasioned by a report that John Dunton will speedily be rewarded with a considerable place or position), (18) ‘King George for ever,’ (19) ‘The Manifesto of King John the Second,’ (20) ‘The Ideal Kingdom,’ (21) ‘The Mob War’ (contains eight political letters and promises eight more), (22) ‘King William's Legacy,’ an heroic poem, (23) ‘Burnet and Wharton, or the two Immortal Patriots,’ an heroic poem, (24) ‘The Pulpit Lunaticks,’ (25) ‘The Bull-baiting, or Sacheverell dressed up in Fireworks,’ (26) ‘The Conventicle,’ (27) ‘The Hanover Spy,’ (28) ‘Dunton's Recantation,’ (29) ‘The Passive Rebels,’ (30) ‘The Pulpit Trumpeter,’ (31) ‘The High-church Martyrology,’ (32) ‘The Pulpit Bite,’ (33) ‘The Pretender or Sham-King,’ (34) ‘God save the King,’ (35) ‘The Protestant Nosegay,’ (36) ‘George the Second, or the true Prince of Wales,’ (37) ‘The Queen by Merit,’ (38) ‘The Royal Pair,’ (39) ‘The Unborn Princes,’ (40) ‘All's at Stake.’ Dunton also advertised in 1723 a volume, the enormous title of which begins ‘Upon this moment depends Eternity;’ it never appeared.

[Dunton's Life and Errors (1705), reprinted in 1818 with life by J. B. Nichols, also in Nichols's Lit. Anecd. v. 59–83.]

L. S.

Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911)

DUNTON, JOHN (1659–1733), English bookseller and author, was born at Graffham, in Huntingdonshire, on the 4th of May 1659. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather had all been clergymen. At the age of fifteen he was apprenticed to Thomas Parkhurst, bookseller, at the sign of the Bible and Three Crowns, Cheapside, London. Dunton ran away at once, but was soon brought back, and began to “love books.” During the struggle which led to the Revolution, Dunton was the treasurer of the Whig apprentices. He became a bookseller at the sign of the Raven, near the Royal Exchange, and married Elizabeth Annesley, whose sister married Samuel Wesley. His wife managed his business, so that he was left free in a great measure to follow his own eccentric devices. In 1686, probably because he was concerned in the Monmouth rising, he visited New England, where he stayed eight months selling books and observing with interest the new country and its inhabitants. Dunton had become security for his brother’s debts, and to escape the creditors he made a short excursion to Holland. On his return to England, he opened a new shop in the Poultry in the hope of better times. Here he published weekly the Athenian Mercury which professed to answer all questions on history, philosophy, love, marriage and things in general. His wife died in 1697, and he married a second time; but a quarrel about property led to a separation; and being incapable of managing his own affairs, he spent the last years of his life in great poverty. He died in 1733. He wrote a great many books and a number of political squibs on the Whig side, but only his Life and Errors of John Dunton (1705), on account of its naïveté, its pictures of bygone times, and of the literary history of the period, is remembered. His letters from New England were published in America in 1867.

Notes & Queries "London Booksellers Series" (1931–2)

DUNTON, JOHN. His book, 'My Life and Errors' has been frequently quoted throughout these notes. He was born in 1659, and died in 1733. In 1673 he was bound apprentice to Thomas Parkhurst, a bookseller of London, and about 1681 he started business on his own account at the sign of the Black Raven in Prince's Street, Poultry, over against the Stock Market. In 1682 he married, and from this date, being himself a bad business man, he left the management of the venture to his wife. 1685 he set sail for America with a cargo of books, intending to try and extend his trade, but he was not so successful as he might have wished. A similar expedition to Ireland in 1698 met with a like fate. In spite of the careful management of his wife, he became bankrupt in 1687, but two years later he set up once again in his old shop, where he continued till 1700. After his return from Ireland he disposed of his stock, and from then till his death in 1733 he worked as a hack writer. His impecuniosity seemed to dog him all his life, in business and out.

He was confined in the Fleet from 1722 to 1723, and, it is said, when he died in 1733, he was living in the direst poverty. His reputation amongst his contemporaries seems to have been a doubtful one. The Stationers' Company, apparently, saw no objection to making him a freeman of their fraternity in 1692, and, according to his own account, he was held in the highest esteem by Samuel Wesley ('Life and Errors,' i. 164–165); but in the 'History of His Own Life' Fuller brought against him charges of a grave character, and accused him of tampering with, and altering his (Fuller's) 'Narrative of the Sham Prince of Wales' before he printed it. Dunton, however, ('Life and Errors' i. 181) rebuts the charge.

—Frederick T. Wood, 15 August 1931

DUNTON, JOHN. It may be worth recording Dunton's variations of imprint as shown in Arber's 'Term Catalogues.' 1681–1695, Black Raven, or Raven, in the Poultry; (a) over against the Stocks Market; (b) over against the Compter; (c) at the corner of Princes Street near the Royal Exchange. 1695, Black Raven, Jewen Street.

—Ambrose Heal, 5 September 1931