Charlotte Smith (1749–1806)

Nicholas Hudson, University of British Columbia

December 2022

Arguably one of the most underrated authors in British literary history, Charlotte Smith pioneered the realist novel, rivalling Frances Burney in her own time as the most admired novelist of the age and influencing Jane Austen, Walter Scott, and Charles Dickens. Smith was also a major poet whose Elegiac Sonnets (1784) was republished throughout her life, influencing Wordsworth. Her posthumous long landscape poem, Beachy Head (1807), is comparable to Wordsworth’s best verse in its rejection of poetic diction and realistic depiction of both the land and its people. Smith exemplified the hard-working professional writer of the late eighteenth century, a best-selling author who nonetheless labored incessantly throughout her career just to keep her large family above water.

Smith’s early life promised a quite different and much easier life. She was born in London in 1749, the eldest daughter of a wealthy landed gentleman Nicholas Turner who had estates in Surrey and Sussex. When Charlotte’s mother Anna died when she was three, however, Nicholas went abroad, squandering his wealth to the point where he saw the need to marry Charlotte at only fifteen to Benjamin Smith, the son of the wealthy Barbados planter and East India merchant Richard Smith. Though designed to become himself a wealthy merchant, Benjamin proved feckless and incompetent, unable to provide for his family and constantly trying to seize Charlotte’s earnings as an author. When Richard Smith died, his fortune of some £36,000 became hopelessly entangled in Chancery, leaving the family without money. Benjamin ended up in King’s Bench Prison for debt where Charlotte stayed with him amidst scenes of despair that she would later recall vividly in her novel Marchmont (1796). Meanwhile Smith and her husband had started a large family with twelve children before their separation.

For Benjamin soon absconded, leaving Charlotte to support the children on her own at various places in south England. Smith turned to writing as a source of income, discovering to everyone’s apparent surprise that she was one of the most talented and marketable authors of her time. As a woman author she at first struggled for acceptance: Richard Dodsley rejected her Elegiac Sonnets contemptuously before William Hayley, then considered a major poet, agreed to be the dedicatee. The commercial and critical success of this volume paved the way for the publication of her adaptation of a collection of legal cases in French, which she entitled The Romance of Real Life. The unexpected success of this book in turn induced the major London bookseller Thomas Cadell to offer her £50 a volume for her first wholly original novel, Emmeline; or, the Orphan of the Castle (1788). Reception of this novel was again enthusiastic, as was the reception of her subsequent Ethelinde; or, the Recluse of the Forest (1789). By the time Smith published Celestina (1789), The Critical Review judged that “In the modern school of novel-writers, Mrs. Smith holds a very distinguished rank; and, if not the first, she is so near as scarcely to be styled an inferior. Perhaps, with Miss Burney she may be allowed to hold ‘a divided sway.’”

Having risen quickly to even magisterial reputation, Smith was now in a position to take chances and develop her generally recognized gifts. In an atmosphere charged by the French Revolution, she wrote a pro-revolutionary novel, Desmond (1792), going to France to get a sense of events on the ground. This work was followed by a second novel deeply critical of the English political, ecclesiastical and legal establishment, Old Manor House (1793), which has remained her most popular and discussed work. Despite the success of both these novels, Smith remained vulnerable. When she published the one-volume novel The Wanderings of Warwick (1794), the bookseller Joseph Bell, who had published Old Manor House, had Smith arrested for failing to fulfil her agreement to publish a two-volume novel. She moved back to Cadell’s firm, again surprising everyone by writing what was viewed as a recantation of her pro-revolutionary views, The Banished Man. This novel followed the struggles of an aristocratic French refugee from Jacobin violence at the outset of the Terror. In Montalbert (1795) she briefly revived the non-political orientation of her early novels, with their sentimentalized heroines. In Marchmont (1796) and The Young Philosopher (1798), however, Smith again launched a scathing critique of the British establishment.

As the result of this critique, the establishment rounded against the one-time celebrated novelist. Reviews of the last two novels particularly condemned her attacks on greedy and dishonest lawyers, blaming this bitter satire on her continuing legal woes with Richard Smith’s unpaid will. Smith’s reputation would never recover from this critique. Throughout the nineteenth century to the present day, Smith has been widely regarded as a novelist who could not separate her private life from her fiction. Oddly, it is a charge leveled most often at women writers. Her novels after Old Manor House have been all but ignored; to this day, there is hardly a single published essay on Marchmont, despite its vigorous experiments with the gothic as the form of social and political critique. In this latter fiction, Smith was virtually inventing the Condition of England novel, using her fiction like Gaskell or Dickens to paint a sweeping and harshly realistic portrait of social injustice and the sufferings of common people. Smith has remained in the shadow of Jane Austen, and often seems valued only to the extent that she foreshadows Austen’s fiction. Yet Smith was a much different and arguably better novelist than Austen in many respects. She marched headlong into the major social issues of her day, covering a geographical and ideological zone far beyond the narrow boundaries of English village life.

Smith exemplifies the artistic achievement of an author who first wrote for money and always had commercial ends in mind. Her friend William Cowper imagined her “chained to her desk like a slave to his oar.” Through all this, however, Smith’s standards of artistry never diminished. The educational writing and poetry of her last years remains of high quality leading to her still admired poem Beachy Head, published shortly after her death in October 1806. Smith was a shrewd and hard bargainer with the leading publishers of her day, including Dodsley, Cadell and Davies, Joseph Bell and Joseph Johnson. From her sixty-three volumes of fiction, poetry and a single unperformed comedy, What is She?, she earned large receipts, opening the way for other woman writers, yet it was only in the last year of her life that she enjoyed any relief from her financial straits. Her estranged husband died early in 1806, freeing up £7000 from the Smith will. The saga of Richard Smith’s disputed will, which was finally whittled to almost nothing by legal fees, would be memorialized in Dickens’s Bleak House. But Dickens also learned from Smith’s innovations as a novelist who showed how to combine gritty detail with imagery drawn from the romance and gothic, creating what Smith herself dubbed “The Romance of Real Life.” In the words of Stuart Curren, Smith’s fiction marks the beginning of “a reconstituted literary realism markedly distinct from that of Richardson, Fielding, and Smollett.” Regrettably, she still awaits a proper revival.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

SMITH, CHARLOTTE (1749–1806), poetess and novelist, the eldest daughter of Nicholas Turner of Stoke House, Surrey, and Bignor Park, Sussex, by his wife, Anna Towers, was born in London on 4 May 1749 at King Street, St. James's. When Charlotte was little more than three years old her mother died, and the child was brought up by an aunt, who sent her at the early age of six to a school at Chichester, and afterwards to another at Kensington. The education thus received was exceedingly superficial, and ceased entirely at the age of twelve, when Charlotte entered society. Two years later she received an offer of marriage, which was refused by her father on the score of her youth. In 1764 the father married a second wife, a woman of fortune. Charlotte's aunt at that time had an aversion to stepmothers, and hurriedly arranged a marriage for her niece with Benjamin Smith, second son of Richard Smith, a West India merchant, and director of the East India Company. The wedding took place on 23 Feb. 1765. The youthful couple (the husband was only twenty-one) lived over the elder Smith's house of business in the city of London, and Charlotte was in enforced attendance on an invalid mother-in-law of exacting disposition. The marriage was not one of affection; both parties had been talked into it by officious relatives, and it is not surprising that Charlotte found life dreary. Her father-in-law, on the death of his wife, married Charlotte's aunt.

Charlotte was now free to indulge her desire of living in the country. Her father-in-law, however, entertained a high opinion of her abilities, and offered her a considerable allowance if she would live in London and assist him in his business. He had on one occasion when he was libelled employed her to write a vindication of his character, a task that she fulfilled admirably. But a town life had never pleased her, and in 1774, with her husband and seven children, she went to live at Lys Farm, Hampshire. Her husband was at one time high sheriff of Hampshire (cf. L'Estrange, Life of M. R. Mitford, iii. 148; Letters of M. R. Mitford, ed. Chorley, 2nd ser. i. 29). But his extravagance and his attempts to realise wild and ruinous projects, propensities somewhat kept in check while he was living in his father's house, began to cause his wife uneasiness. She once expressed to a friend a desire that her husband should find rational employment. The friend suggested that his enthusiasm might be directed towards religion. ‘Oh!’ replied Charlotte, ‘for heaven's sake do not put it into his head to take to religion, for if he does he will instantly begin by building a cathedral’ (Nichols, Illustrations, viii. 35). In 1776 the elder Smith died, leaving a complicated will. The ensuing litigation increased the pecuniary difficulties of Charlotte and her husband; the Hampshire estate was sold, and in 1782 Smith was imprisoned for debt. His wife shared his confinement, which lasted for seven months.

For some years Charlotte Smith had been in the habit of writing sonnets, and it occurred to her that her compositions might afford a means of livelihood. She showed fourteen or fifteen of them to Dodsley, and afterwards to Dilly, but neither would publish them. She then appealed to Hayley—known to her by reputation, and a neighbour of her family in Sussex—who permitted her to dedicate to him a thin quarto volume of sonnets (‘Elegiac Sonnets and other Essays’). It was printed at Chichester at her own expense, and published by Dodsley at Hayley's persuasion in 1784. The poems found favour with the public; a second edition was called for the same year, and a fifth in 1789. They were reissued with a second volume and plates by Stothard, under the title of ‘Elegiac Sonnets and other poems,’ in 1797. Among the subscribers to that edition were the archbishop of Canterbury, Cowper, Charles James Fox, Horace Walpole, Mrs. Siddons, and the two Wartons. There were altogether eleven editions of the poems, the last dated in 1851.

But the circumstances of Mrs. Smith's family scarcely improved. They lived for a while in a dilapidated chateau near Dieppe in France, and there Mrs. Smith translated Prévost's ‘Manon Lescaut’ (1785), and wrote the ‘Romance of Real Life,’ an English version of some of the most remarkable trials from ‘Les Causes Célèbres;’ it appeared in 1786. About this time the family returned to England and settled at Woolbeding House, near Midhurst in Sussex. Mrs. Smith soon decided that a separation from her husband would be best for all concerned. The only reason assigned was incompatibility of temper, and the children remained with the mother. The husband and wife occasionally met and constantly corresponded; Mrs. Smith continued to give her husband pecuniary assistance, but firmly refused to live with him again. He died in March 1806.

In 1788 Charlotte Smith published her first novel, ‘Emmeline, or the Orphan of the Castle,’ in 4 vols., and it was so successful that her publisher, Cadell, supplemented the sum originally paid. It was admired by Sir Egerton Brydges and Sir Walter Scott. The latter indulgently declared the ‘tale of love and passion’ to be ‘told in a most interesting manner,’ praised the mingling of humour and satire with pathos, and considered that the ‘characters both of sentiment and of manners were sketched with a firmness of pencil and liveliness of colouring which belong to the highest branch of fictitious narrative.’ Hayley was even more extravagant in his praises (cf. Nichols, Lit. Illustr. vii. 708). Miss Seward, on the other hand, found it a servile imitation of Miss Burney's ‘Cecilia;’ and stated that the characters of Mr. and Mrs. Stafford were drawn from Mrs. Smith and her husband (Letters, ii. 213). A second novel, ‘Celestina,’ in 4 vols., came out in 1792, and was characterised as ‘a work of no common merit’ (cf. Nichols, Lit. Illustr. vii. 715), and a third, ‘Desmond,’ in 3 vols., in 1792. The character of Mrs. Manby in the last is said to represent Hannah More (Seward, Letters, iii. 329). In 1792 Mrs. Smith visited Hayley at Eartham, and met there Cowper, and probably Romney (Hayley, Memoirs, i. 432). ‘The Old Manor House,’ in 4 vols., considered by Scott her best piece of work, appeared in 1793.

Failing health was now added to the ever present pecuniary and family troubles. But Mrs. Smith's cheerful temperament enabled her to abstract herself from her cares, and publish a novel each year till 1799. Caldwell, writing to Bishop Percy in 1801, says: ‘Charlotte Smith is writing more volumes of “The Solitary Wanderer” for immediate subsistence. … She is a woman full of sorrows. One of her daughters made an imprudent marriage, and the man, after behaving extremely ill and tormenting the family, died. The widow has come to her mother not worth a shilling, and with three young children’ (Nichols, Lit. Illustr. viii. 38). In 1804 appeared her ‘Conversations introducing Poetry,’ a book treating chiefly of subjects connected with natural history for the use of children. It contains her versions of the well-known poems ‘The Ladybird’ and ‘The Snail.’ During the latter years of her life Mrs. Smith made many changes of residence, living at London, Brighthelmstone, and Bath. In 1805 she removed to Tilford, near Farnham in Surrey, where she died on 28 Oct. 1806. She was buried in Stoke church, near Guildford; a monument by Bacon marks her resting-place. Of her twelve children, eight survived her. Her youngest son, George Augustus, a lieutenant in the 16th foot, died at Surinam on 16 Sept., five weeks before his mother; another son, Lionel [q. v.], was a distinguished soldier.

If there is nothing great in Mrs. Smith's poems, they are ‘natural and touching’ (cf. Leigh Hunt, Men, Women, and Books, ii. 139). Miss Mitford told Miss Barrett that she never took a spring walk without feeling Charlotte Smith's love of external nature and her power of describing it (cf. L'Estrange, Life of M. R. Mitford, iii. 148), and in a letter to Mrs. Hofland declared that ‘she had, with all her faults, the eye and the mind of a landscape poet’ (Letters of M. R. Mitford, ed. Chorley, 2nd ser. i. 29). As a novelist she shows skill in portraying character, but the deficiencies of the plots render her novels tedious. Her English style is good, and it is said that whenever Erskine had a great speech to make, he used to read Charlotte Smith's works in order to catch their grace of composition (L'Estrange, Life of M. R. Mitford, iii. 299).

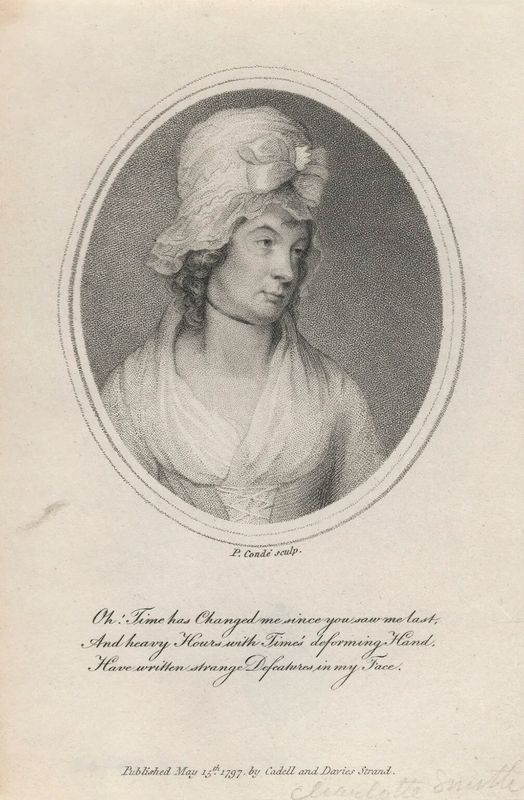

Her portrait was painted by Opie. A drawing from the picture by G. Clint, A.R.A., was engraved by A. Duncan and by Freeman. There is an engraving by Ridley and Holt of what seems to be another picture, and an unsigned engraving in which Mrs. Smith is represented in a curious dress. Her head in outline appears in ‘Public Characters’ (1800–1).

Other works by Charlotte Smith are: 1. ‘Ethelinde, or the Recluse of the Lake,’ 5 vols. 1790; 2nd edit. 1814. 2. ‘The Banished Man,’ 4 vols. 1794. 3. ‘Montalbert,’ 1795. 4. ‘Marchmont.’ 5. ‘Rural Walks.’ 6. ‘Rambles Farther,’ 1796. 7. ‘Minor Morals interspersed with Sketches,’ 2 vols. 1798; other editions 1799, 1800, 1816, 1825. 8. ‘The Young Philosopher,’ a novel, 1798. 9. ‘The Solitary Wanderer,’ 1799. 10. ‘Beachy Head,’ a poem, 1807.

[Scott's biography, the facts for which were communicated to him by Mrs. Dorset, a sister of Charlotte Smith, in Miscellaneous Prose Works, i. 349–59, is the chief authority; see also Elwood's Literary Ladies, i. 284–309; Mathias's Pursuits of Lit. pp. 56, 58.]

E.L.

Dictionary of National Biography, Errata (1904), p. 253

N.B.— f.e. stands for from end and l.l. for last line

Page Col. Line 29 i 21 Smith, Charlotte: for Tetford read Tilford

Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911)

SMITH, CHARLOTTE (1749–1806), English novelist and poet, eldest daughter of Nicholas Turner of Stoke House, Surrey, was born in London on the 4th of May 1749. She left school when she was twelve years old to enter society. She married in 1765 Benjamin Smith, son of a merchant who was a director of the East India Company. They lived at first with her father-in-law, who thought highly of her business abilities, and wished to keep her with him; but in 1774 Charlotte and her husband went to live in Hampshire. The elder Smith died in 1776, leaving a complicated will, and six years later Benjamin Smith was imprisoned for debt. Charlotte Smith's first publication was Elegiac Sonnets and other Essays (1784), dedicated by permission to William Hayley, and printed at her own expense. For some months Mrs Smith and her family lived in a tumble-down château near Dieppe, where she produced a translation of Manon Lescaut (1785) and a Romance of Real Life (1786), borrowed from Les Causes Célèbres. On her return to England Mrs Smith carried out a friendly separation between herself and her husband, and thenceforward devoted herself to novel writing. Her chief works are: — Emmeline, or the Orphan of the Castle (1788); Celestina (1792); Desmond (1792); The Old Manor House (1793); The Young Philosopher (1798); and Conversations introducing Poetry (1804). She died at Tilford, near Farnham, Surrey, on the 28th of October 1806. She had twelve children, one of whom, Lionel (1778-1842), rose to the rank of lieutenant-general in the army. He became K.C.B. in 1832 and from 1833 to 1839 was governor of the Windward and Leeward Islands.

Charlotte Smith's novels were highly praised by her contemporaries and are still noticeable for their ease and grace of style. Hayley said that Emmeline, considering the situation of the author, was the most wonderful production he had ever seen, and not inferior to any book in that fascinating species of composition (Nichols, Illustrations of Literature, vii. 708). The best account of Mrs Smith is by Sir Walter Scott, and is based on material supplied by her sister, Mrs Dorset, with a detailed criticism of her work by Scott (Misc. Prose Works, 1841, i. 348-359). Charlotte Smith is best remembered by her charming poems for children.