Henry Fielding (1707–1754)

Note: the 19th- and early 20th-century biographies below preserve a historical record. A new biography that reflects 21st-century approaches to the subjects in question is forthcoming.

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

FIELDING, HENRY (1707–1754), novelist, born at Sharpham Park, near Glastonbury, Somersetshire, 22 April 1707, was the son of Edmund Fielding (1676–1741), an officer in the army, by Sarah, daughter of Sir Henry Gould of Sharpham Park, a judge of the king's bench. Edmund Fielding was third son of John Fielding, canon of Salisbury, grandson of George Feilding, earl of Desmond, and great-grandson of William Feilding, first earl of Denbigh [q. v.] The mother of Lady Mary W. Montagu was also a granddaughter of the Earl of Desmond, and Lady Mary was thus Henry Fielding's second cousin. Kippis reports the familiar anecdote that the novelist accounted for the difference between his name and that of the other Feildings by saying that his branch of the family had been the first to learn to spell (Nichols, Lit. Anecd. iii. 384). Soon after Edmund Fielding's marriage, Sir Henry Gould made a will (March 1706) leaving 3,000l. to be invested in an estate for the sole use of his daughter and her children. Her husband, probably for good reasons, was to have ‘nothing to do with it.’ Two daughters, Catharine and Ursula, were apparently born at Sharpham. After Gould's death (March 1710) the Edmund Fieldings moved to East Stour (or Stower) in Dorsetshire, where were born Sarah [q. v.], Anne (died young), Beatrice, and Edmund who entered the navy and died without children. The four sisters survived their brother. and were known to Richardson (Austin Dobson, p. 140; Nichols, Lit. Anecd. ix. 589; Murphy). were all buried in Hammersmith Church—9 July 1750, 12 Nov. 1750, and 24 Feb. 1750–1 respectively. Henry was educated by a Mr. Oliver, curate of Motcombe, said by Murphy to be the original of Trulliber, and at Eton, where he was a contemporary of George Lyttelton, Charles Hanbury (afterwards Williams), and Winnington, his friends in later life, and also of Pitt, Fox, and Charles Pratt (Lord Camden). He had hardly left Eton when he had a stormy love-affair with Sarah, only daughter and heiress of Solomon Andrew, a merchant of Lyme Regis. Her father was dead, and her guardian, Andrew Tucker, complained (in November 1725) that he went in fear of his life from the behaviour of Fielding and his man. Miss Andrew was sent to another guardian, Mr. Rhodes of Modbury in South Devonshire, to whose son she was married soon afterwards (1726) (Athenæum, 10 Nov. 1855 and 2 June 1883; extracts from Lyme Regis records). Fielding made a burlesque translation of part of the second satire of Juvenal, afterwards printed in the ‘Miscellanies.’ This, he says, was the ‘only revenge taken by an injured lover’ (Preface to Miscellanies). He was sent to study law at Leyden under the ‘learned Vitriarius.’. He is said to have studied hard; but he certainly began to write plays during his studentship. A failure of remittances, according to Murphy, caused his return. His father had married a widow, Elizabeth Rasa, by whom he had six sons, including John [q. v.] He nominally allowed Henry 200l. a year, but, as the latter used to say (Murphy), ‘any body might pay it that would.’ Edmund Fielding became a major-general in 1735 and a lieutenant-general in 1739, and died (aged 65) on 20 June 1741.

Fielding was a man of great constitutional vigour; over six feet in height, and remarkably powerful and active. He threw himself recklessly into the pleasures of London life, and to supply his wants had to choose (M. W. Montagu, 1837, iii. 93) between the career of a hackney coachman and that of a hackney writer. He began by writing plays, then the most profitable kind of literature. His first performance, ‘Love in several Masques’—a comedy of the Congreve school—was brought out at Drury Lane in Feb. 1728. He acknowledges in the preface the kindness of Wilkes and Cibber ‘previous to its representation.’ It would therefore appear that his residence and certainly his studies at Leyden had been interrupted before his departure. His name appears in the ‘Leyden Album’ on 16 March 1728 (see Peacock, Index; and ‘A Scotchman in Holland’ in Cornhill Mag. for November 1863), a date which would apparently imply a return to Leyden. The play, though eclipsed by the contemporary ‘Beggar's Opera,’ was well received. A more carefully written comedy in the same vein, the ‘Temple Beau,’ was acted in January 1730 at Goodman's Fields. Fielding now became a regular playwright, and before the age of thirty produced a great number of comedies, farces, and burlesques. He wrote in haste whatever was likely to catch the public. He had few scruples of delicacy, though he claims a certain moral purpose for sufficiently offensive performances. Even the ‘Modern Husband’ (1732), one of the coarsest, dedicated to Sir Robert Walpole, and respectfully submitted to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (as appears from letters published in her life), was intended, according to the prologue, to make ‘modern vice detestable.’ Two adaptations from Molière, the ‘Mock Doctor’ (1732), from the ‘Médecin malgré lui,’ and the ‘Miser’ (1733), from the ‘Avare,’ appear to have been among his most successful comedies. His burlesques, however, gave the first intimation of his real genius. The farce of ‘Tom Thumb,’ acted at the Haymarket in 1730, and with an additional act in 1731, in which he burlesques all the popular playwrights of the day, is still amusing, and long kept the stage in a version by Kane O'Hara (1780). According to Mrs. Pilkington (Memoirs, iii. 93), Swift told her that he had only laughed twice in his life, once at Tom Thumb's killing the ghost. She adds that Swift admired Fielding's wit. A contemptuous reference to him in the ‘Rhapsody’ was afterwards altered by the substitution of ‘the Laureate’ (Cibber) for Fielding. In spite of the oblivion into which the objects of his satire have fallen, it has not yet lost the claim due to its exuberant fun.

Fielding's plays only filled his pockets for the moment. The anonymous author of ‘A Seasonable Reproof’ (1735) describes him as appearing one day in the velvet which was in pawn the day before. A burlesque author's will (reprinted from Oldys's ‘Universal Spectator’ in the ‘Gentleman's Magazine,’ July 1734) ridicules his taste and carelessness. A story has often been reprinted that Fielding kept a booth at Bartholomew fair in 1733. It is, however, conclusively shown by Mr. F. Latreille (Notes and Queries, 5th ser. iii. 502) that the booth was really kept by Timothy Fielding, an actor.

In the autumn of 1733 a revolt, headed by Theophilus Cibber, took away many of the actors from Drury Lane, which was further threatened by the competition of a new theatre in Covent Garden. Fielding thought that Highmore, the patentee at Drury Lane, had been badly treated. He heartily supported the ‘distressed actors’ at Drury Lane. Mrs. Clive also stood by them. For her Fielding adapted the ‘Intriguing Chambermaid’ from Regnard's ‘Retour Imprévu’ (not from ‘Le Dissipateur’ by Destouches, as has been erroneously stated). It was acted 15 Jan. 1734, and published with a prefatory epistle, in which Mrs. Clive received very warm and obviously sincere compliments. The ‘Author's Farce,’ originally produced in 1730, was revived on the same occasion, with additional scenes smartly satirising the Cibbers. From their action on this occasion, and from a natural antipathy to their characters, Fielding henceforward carried on a steady warfare against both father and son. He remodelled a play already begun at Leyden, ‘Don Quixote in England,’ for the Drury Lane company. It contains some good political satire, but is chiefly remarkable as a proof of Fielding's lifelong admiration of Cervantes. The return of the revolted players to Drury Lane caused its transference to the Haymarket, where it was acted in April 1734. In the beginning of 1735 the farce called finally ‘The Virgin Unmasked,’ written for Mrs. Clive, and a comedy called ‘The Universal Gallant,’ and deservedly damned, were acted at Drury Lane.

A period of inactivity followed, to which his first marriage has been generally assigned. ‘The Universal Gallant,’ The lady was Charlotte Cradock, one of three sisters living on their own means at Salisbury. Richardson says that she was an illegitimate child (Correspondence, iv. 69). Murphy states that she had 1,500l., and that Fielding's ‘mother dying about this time’ (in reality seventeen years before) he inherited an estate of about 200l. a year at Stower in Dorsetshire. His extravagance and conviviality, according to Murphy, ‘entirely devoured’ his wife's ‘little patrimony’ ‘in less than three years.’ The ‘costly yellow liveries’ of his servants mentioned by Murphy really belonged to Robert Feilding [q. v.] The statement is unsatisfactory, but it is probable that Booth's account in ‘Amelia’ of his life in the country represents the facts: that Fielding was extravagant, and that the neighbouring squires disliked and misrepresented the Londoner, who certainly had an eye for their foibles. Love poems to ‘Celia,’ printed in the ‘Miscellanies,’ show that Fielding must have been already courting Miss Cradock in 1730. The Sophia of ‘Tom Jones’ clearly represents her person (bk. iv. ch. ii.), and probably her mind. Lady Louisa Stuart, in the anecdotes prefixed to Lady Mary W. Montagu's works, says that she was as beautiful and amiable as the ‘Amelia.’ Amelia, according to Richardson (ib. iv. 60), was his first wife, ‘even to her noselessness.’ Lady L. Stuart also says that she had really suffered the accident described in the novel, ‘a frightful overturn, which destroyed the gristle of her nose.’ The husband and wife loved each other passionately, and in spite of the errors of Fielding's earlier life he was always a devoted husband and father.

Fielding was back in London in the beginning of 1736, when he took the little theatre in the Haymarket. He opened it with his ‘Pasquin; a Dramatick Satire on the Times,’ in which, in a series of scenes on the plan of the ‘Rehearsal,’ he attacks the political corruption of Walpole's time. Mrs. Charke [q.v.] (Narrative, p. 63) acted in this, and made sixty guineas at her benefit. The piece had a run of fifty nights; and he endeavoured to follow it up next year by the ‘Historical Register for 1736.’ This contains a sharp attack upon Sir Robert Walpole as Quidam (Coxe, Life of Walpole). Fielding was a strong whig, but was now joining with most of his distinguished contemporaries of all parties in the opposition to the ministry. Sir John Barnard had already, in 1735, brought in a bill to restrict the license of the stage. It is said (ib. i. 516) that Giffard, manager of Goodman's Fields, showed a manuscript farce called ‘The Golden Rump’ to Walpole. Horace Walpole attributes this to Fielding, and says (Memoirs of George II, i. 12) that he found a copy among his father's papers. Sir Robert Walpole bought the copy, and read a selection of objectionable passages to the house (Rambler's Magazine, 1787). It is also alleged that Walpole had himself procured it to be written in order to give a pretext for restrictive measures. This is highly improbable. In any case, a bill was introduced in 1737, making a license from the lord chamberlain necessary for all dramatic performances. It was opposed in a famous speech by Lord Chesterfield, who, at the same time, spoke, perhaps ironically, of the excessive license of ‘Pasquin.’ The bill received the royal assent 21 June 1737, and put an end to Fielding's enterprise. He produced three flimsy pieces in the early part of 1737. Two plays afterwards produced, the ‘Wedding Day’ (1743) and the posthumous ‘Good-natured Man,’ had been written long before.

Fielding thus gave up play-writing at the age of thirty, and for the rest of his life laboured hard to retrieve his fortune and maintain his family. He entered the Middle Temple (1 Nov. 1737), when he is described as of ‘East Stour.’ Murphy says that he died vigorously, and often left a tavern late at night to abstract the works of ‘abstruse authors’ for several hours. He was called to the bar 20 June 1740, and joined the western circuit. He is said (Hutchins, Dorset) to have regularly attended the Wiltshire sessions; but he did not succeed at the bar. While a student at the Temple he joined with James Ralph [q. v.] in editing a periodical paper called ‘The Champion.’ Ralph was at this time much employed by the adherents of Frederick, prince of Wales, and especially by Dodington, to whom, in 1741, Fielding addressed a poetical epistle on ‘True Greatness.’ The ‘Champion’ is one of the innumerable imitations of the ‘Spectator;’ and Fielding's essays (signed C. and L.) are attempts to work a nearly exhausted vein. While the ‘Champion’ was running, Cibber published his ‘Apology.’ In the eighth chapter there were some irritating references to Fielding as a ‘broken wit,’ who had sought notoriety by personal scurrility and abuse of the government. Fielding retorted by a vigorous attack in the ‘Champion.’ The papers were reprinted by Curll in a pamphlet called ‘The Tryal of Colley Cibber, Comedian.’ An ‘Apology for the Life of Mr. The. Cibber, Comedian’ (1740), has also been attributed to Fielding, but the internal evidence is conclusive against an attribution which rests upon mere guess.

Richardson's ‘Pamela’ appeared in November 1740, and at once became popular. Fielding, irresistibly amused by the prudery and sentimentalism of the book, began a parody, in which Pamela's brother was to be tempted by a lady as Pamela is tempted by the squire. The book, called ‘The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and his friend Mr. Abraham Adams,’ developed as it was written, especially by the introduction of the famous Parson Adams. It is generally admitted that the prototype of Adams was William Young (d. 1757), who had many of the parson's oddities, and who in 1752 undertook to co-operate with Fielding in a translation of Lucian, never executed. Fielding speaks of this in the ‘Covent Garden Journal,’ and remarks that he has ‘formed his style upon that very author’ (Lucian). Young also co-operated with Fielding in ‘Plutus,’ a translation from Aristophanes, in 1742. ‘Joseph Andrews’ professes to be written in imitation of the manner of Cervantes, and resemblances have also been traced to Marivaux’ ‘Marianne’ and to Scarron's ‘Roman Comique’ (both of whom Fielding quotes), but the substantial originality is undeniable. The book was published in February 1742. The original assignment to Millar, preserved in the Forster collection at South Kensington, shows that Fielding received for it 183l. 11s. Richardson resented Fielding's attack with a bitterness which finds frequent vent in his correspondence, even with Sarah Fielding, and is not the less offensive because it takes a high moral tone. Citations from some letters to Aaron Hill and his daughters given by Mr. Austin Dobson (pp. 137–40), from the originals in the Forster collection, curiously illustrate a feeling which appears never to have been retorted by Fielding.

The same assignment includes a payment of 5l. 5s. to Fielding for a ‘Vindication’ of the Duchess of Marlborough's account of her conduct. Fielding probably received some additional payment from the duchess. Garrick was now making his first appearance in London. Hawkins (Life of Johnson, p. 45) says that he gave a private performance of Fielding's ‘Mock Doctor’ at Cave's rooms in St. John's Gate. He asked Fielding, whose acquaintance he soon made, to provide a part for him. Fielding had two early plays by him, the ‘Good-natured Man’ and the ‘Wedding Day.’ He revised the latter, though greatly troubled by a dangerous illness of his wife, and it was produced 17 Feb. 1743. It ran only six nights, and the author made under 50l. (Preface to Miscellanies). Murphy says that Fielding had refused to alter a dangerous passage, saying ‘Damn them [the audience], let them find that out.’ When it was actually hissed, he was drinking a bottle of champagne and chewing tobacco (simultaneously, it is suggested) in the green-room. Hearing that the passage had been hissed, he observed, ‘Oh, damn them, they have found it out, have they?’ The story must be taken for what it is worth, and Fielding's remarks on the failure (ib.) show that his insensibility was in any case not permanent. The play was published in February 1743. In 1743 also appeared his three volumes of ‘Miscellanies,’ which reached a second edition in the same year. The book was published by subscription, and the list mentions over four hundred subscribers, including many ‘persons of quality,’ lawyers, and actors. His old enemy, Robert Walpole, now Earl of Orford, took ten copies; and Fielding speaks warmly of him in his ‘Voyage to Lisbon.’ The number of copies subscribed for was 519, which would apparently produce about 450l. It includes some previously published pieces and early poems, and miscellaneous essays and plays; but the two most remarkable items are the ‘Journey from this World to the Next’—including some clever satire and a passage describing a meeting with a dead child, which was greatly admired by Dickens (Letters, i. 394)—and the life of ‘Jonathan Wild the Great,’ which occupies the whole of the third volume. It is one of Fielding's most powerful pieces of satire, and is scarcely surpassable in its peculiar kind, unless by Thackeray's ‘Barry Lyndon.’

Fielding probably lost his wife soon afterwards. In the preface he says he was ‘laid up with the gout’ in the winter of 1742–3, ‘with a favourite child dying in one bed, and my wife in a condition very little better on another, attended with other circumstances’ (probably bailiffs), ‘which served as very proper decorations to such a scene.’ He declared that he has written nothing in any public paper since June 1741, and that he never was or would be ‘author of any anonymous scandal on the private history or family of any person whatever.’ He solemnly promises that he will never again write anonymously. Other references prove that his wife was still alive and allude to the loss of a daughter, ‘one of the very loveliest creatures ever seen’ (see Austin Dobson, pp. 107, 108). The wife, whose health had suffered from the struggles which they had to undergo, probably died at the end of 1743. Fielding, as Murphy says, was so broken down by the loss, that his friends feared for his reason. A daughter, Eleanor Harriett, survived and accompanied him on his last voyage to Lisbon. He speaks of a son and daughter in the ‘True Patriot’ in November 1745, though apparently no son survived his first wife. The burial of a James Fielding, son of Henry Fielding, is recorded on 19 Feb. 1736 in the register of St. Giles-in-the-Fields (ib. p. 110).

A preface to the ‘David Simple’ (1744) of his sister, Sarah Fielding [q. v.], disclaims various anonymous works attributed to him, especially the ‘Causidicade,’ and complains of the reports as likely to injure him in a profession in which he is entirely absorbed. He renounces all literary ambition, but in the same breath withdraws his promise to write no more. During the rebellion of 1745 he published the ‘True Patriot,’ a weekly paper in support of the government, and in December 1747 the ‘Jacobite's Journal,’ continued till November 1748, continuing the same design. A rude woodcut at the head has been attributed to Hogarth, one of the friends whom Fielding never tired of praising. A compliment to ‘Clarissa Harlowe’ is also noteworthy.

On 27 Nov. 1747 Fielding was married, at St. Benet's, Paul's Wharf, to Mary Daniel (whose name has also been given as MacDaniel and Macdonald). She is described in the register as ‘of St. Clement Danes, Middlesex, Spinster.’ Their first child was christened three months afterwards. Lady Louisa Stuart reports that the second wife had been the maid of the first wife. She had ‘few personal charms,’ but had been strongly attached to her mistress, and had sympathised with Fielding's sorrow at her loss. He told his friends that he could not find a better mother for his children or nurse for himself. The result fully justified his opinion. About the time of his marriage Fielding was living at Back Lane, Twickenham, ‘a quaint, old-fashioned wooden structure,’ demolished between 1872 and 1883 (R. S. Cobbett, Memorials of Twickenham, pp. 358–9).

In December 1748 Fielding was appointed a justice of the peace for Westminster. He moved to Bow Street, to a house belonging to the Duke of Bedford (Bedford Cor. i. 588, ii. 35). He was afterwards qualified to act for Middlesex. The appointment was due to his old schoolfellow Lyttelton, who had introduced him to the Duke of Bedford (dedication of Tom Jones). In the dedication of ‘Tom Jones’ Fielding says that he ‘partly owes his existence to Lyttelton during his composition of the book,’ and that it would never have been completed without Lyttelton's help. Sir John Fielding [q. v.] speaks of ‘a princely instance of generosity’ shown by the Duke of Bedford to his brother, which is also acknowledged in the dedication. Another of Fielding's patrons was Ralph Allen, to whom there is a reference in ‘Joseph Andrews.’ Allen's name, however, does not appear among the subscribers to the ‘Miscellanies.’ Derrick says that Allen sent Fielding a present of 200l. before making his acquaintance (Letters, ii. 93). ‘Tom Jones’ is said to have been written at Twerton-on-Avon, near Bath, where there is still a house called ‘Fielding's Lodge’ (Notes and Queries, 5th ser. xi. 208). Fielding while at Twerton dined almost daily with Ralph Allen (Kilvert, Ralph Allen at Prior Park, 1857). These protectors, whose kindness is warmly acknowledged by Fielding, probably helped him through the years preceding his appointment.

‘Tom Jones,’ described in the dedication as the ‘labour of some years of my life,’ appeared on 28 Feb. 1749. Horace Walpole mentions (Letters, by Cunningham, ii. 163), in May 1744, that Millar had paid him 600l. for the book, and had added 100l. upon its success (Notes and Queries, 6th ser. viii. 288, 314, ix. 54). Fielding's great novel was popular from the first. It has been translated into French, German, Spanish, Dutch, Russian, and Swedish. It was dramatised at home and abroad. In 1769 Joseph Reed turned it into a comic opera, performed at Covent Garden; J. H. Steffens made it into a German comedy; and in 1765–6 it was transformed into a comédie lyrique by Poinsinet, of which Mr. Austin Dobson gives an amusing specimen. In 1785 ‘Tom Jones à Londres,’ by a M. Desfarges, was played at the Théâtre Français. The most recent adaptation is ‘Sophia,’ by Mr. Robert Buchanan (1886), who has since (1888) dramatised ‘Joseph Andrews’ as ‘Joseph's Sweetheart.’ ‘Amelia’ followed ‘Tom Jones’ on 19 Dec. 1751. Millar is said to have paid 1,000l. for the copyright. He adopted some devices in consequence of which a second edition was called for on the day of publication. Johnson ‘read it through without stopping’ (Boswell, 12 April 1776), and said that the heroine was ‘the most pleasing of all the romances;’ but he added, ‘that vile broken nose, never cured, spoilt the sale of perhaps the only book of which, being printed off betimes one morning, a new edition was called for before night’ (Piozzi, Anecdotes, p. 221). Yet Johnson preferred Richardson to Fielding, whom he called a ‘blockhead,’ by which, as he explained, he meant ‘a barren rascal’ (Boswell, 6 April 1774). The original edition of ‘Amelia’ contained some curious little puffs of a proposed ‘Universal Register Office’ or advertising agency, which Fielding with his brother John was endeavouring to start. Fielding's last purely literary performance was the ‘Covent Garden Journal,’ a bi-weekly paper, from January to November 1752. It brought him various quarrels with Sir John Hill, Smollett, and Bonnell Thornton.

Fielding was meanwhile labouring energetically as a magistrate. A passage in the above-mentioned letter from Walpole describes an intrusion made upon Fielding by Rigby and Peter Bathurst. They found him at supper on some ‘cold mutton and a bone of ham, both in one dish, and the dirtiest cloth.’ With him were ‘a blind man’ (clearly his brother, Sir John), ‘a whore’ (a polite way of describing his wife), and ‘three Irishmen.’ Rigby, according to Walpole, had often seen him ‘beg a guinea of Sir C. Williams,’ and he had ‘lived for victuals’ at Bathurst's father's. The insolence of Fielding's visitors is obvious, and Walpole adds his own colouring. The anecdote shows rather that Fielding's position was despised by Walpole's friends than that there was anything really ‘humiliating’ (in Scott's phrase) about it. The position, however, of a justice was at that time regarded with suspicion, as appears from references in Fielding's own plays. On 12 May 1749 Fielding was unanimously chosen chairman of quarter sessions at Hicks's Hall, and on 29 June delivered a very careful and serious charge to the Westminster grand jury. He published in the same year a pamphlet, justifying the execution of one Bosavern Penlez, convicted of joining in a riot and the plunder of a house by some sailors. In January 1750 he published an ‘Inquiry’ into the increase of robbers in London, with suggestions for remedies. It was dedicated to Hardwicke, then lord chancellor, and insists gravely upon the social evils of the time, especially upon the excessive gin-drinking which then caused much alarm, and led to the passage of a restrictive bill that summer. Walpole (Memoirs of George II, i. 44) mentions the influence of Fielding's ‘admirable treatise.’ Hogarth's famous ‘Gin Lane,’ published in February 1751, contributed to the impression due to his friend's writing. Fielding frequently advertises in the ‘Covent Garden Journal’ to request that notices of thefts and burglaries may be sent to his house in Bow Street. In 1752 he published and distributed a curious little pamphlet giving accounts of providential detections of murderers. In January 1753 he published a ‘proposal for making an effectual provision for the poor,’ containing a very elaborate scheme for the erection of a county poor-house. Fielding's remarks upon the operations of the poor laws show both knowledge and intelligent reflection, though he attracted little attention at the time. Later in 1753 he became conspicuous by his connection with the famous case of Elizabeth Canning. He took [see under Canning, Elizabeth] a questionable part in his zeal to protect what he regarded as injured innocence, and defended himself in a pamphlet called ‘A Clear Case of the State of Elizabeth Canning.’ He was attacked by Sir John Hill, and seems to have taken a rather singular view of his duties. In March 1753 he made a raid upon a gambling-house, where he expected to find certain highwaymen (Gent. Mag. March 1753). His health was now rapidly breaking. He was easily persuaded to adopt quack remedies. At the end of 1749 he had a severe attack of fever and gout, and was under the care of Dr. Thomson, who had the credit of killing Pope in 1744 (Carruthers, p. 383) and Winnington in 1746, and was one of Dodington's hangers-on (see Cumberland, Memoirs). In 1751 he testifies to the effect of a wonderful spring at Glastonbury, which had been revealed in a dream to a man who was cured of an asthma by its waters. Fielding declares (London Daily Advertiser, 31 Aug. 1751; Gent. Mag. September 1751) that he had been himself relieved from an illness. In August 1753, after taking ‘the Duke of Portland's medicine’ for nearly a year as a remedy for gout, he was ordered to Bath. He was detained in London by a summons from the Duke of Newcastle to give his advice upon a scheme for suppressing robbers. Fielding devised a plan, which consisted in providing informers by a fund supplied for the purpose. He succeeded by great activity in breaking up a gang, and during the following November and December London was free from the usual outrages. His own health was completely ruined. He was harassed by anxiety for his family. The justice was paid partly by fees. By making up quarrels and refusing the last shillings of the poor he reduced ‘500l. a year of the dirtiest money on earth to little more than 300l.,’ most of which went to his clerk. Something also came from the ‘public service money.’ Throughout the next summer he was failing. He was desperately ill in March 1754, when a severe winter still lingered, but gained some relief from the treatment of Ward, known for his ‘drop.’ In May he moved to his little house, Fordhook, at Ealing. Berkeley's ‘Siris’ put him upon drinking tar-water. He fancied that this, like his other experiments, did him some good, but it became evident that there was no hope of real improvement except in a warmer climate. He sailed for Lisbon with his wife, daughter, and two servants. He embarked at Rotherhithe 26 June 1754. After many delays his ship, the Queen of Portugal, anchored off Ryde on 11 July, and was detained until the 23rd. Lisbon was at last reached. The incidents of his voyage are detailed with great humour and with undiminished interest in life in the posthumously published ‘Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon.’ Mr. Austin Dobson rightly says that it is one ‘of the most unfeigned and touching little tracts in our own or any other literature.’ A Margaret Collier (Richardson, Correspondence, ii. 77), daughter of Arthur Collier [q. v.] [see Benson, Collier, p. 162), apparently went with Fielding to Lisbon, and was supposed to have written the book, because it was so inferior to his other works. The gallant spirit with which Fielding met this trying experience doubtless sustained him to the last. He died at Lisbon, after two months' stay, 8 Oct. 1754. He was buried at the English cemetery. A tomb was erected by the English factory, and was replaced in 1830 by another, erected through the exertions of the British chaplain, the Rev. Christopher Neville. Mrs. Fielding died at Canterbury 11 March 1802. The children were brought up by their uncle, Sir John, and by Ralph Allen, who made them a liberal yearly allowance. These were (1) William, baptised 25 Feb. 1748; (2) Mary Amelia, 6 Jan. 1749 (buried 17 Dec. 1749); (3) Sophia, 21 Jan. 1750; (4) Louisa, 3 Dec. 1752 (buried at Hammersmith 10 May 1753); (5) Allen, 6 April 1754. William Fielding joined the northern circuit, became about 1808 a magistrate for Westminster, and died in October 1820 (Gent. Mag. 1820, ii. 373–4). He is said to have inherited his father's conversational powers, but had little business (Lockhart, Life of Scott, ch. 1.; Life of Lord Campbell, i. 197). Southey mentions in a letter to Sir Egerton Brydges in 1830 that he had met Fielding about 1817, when he was a fine old man, ‘though visibly shaken by time.’ Allen became a clergyman, and at his death in 1823 was vicar of St. Stephen's, Canterbury.

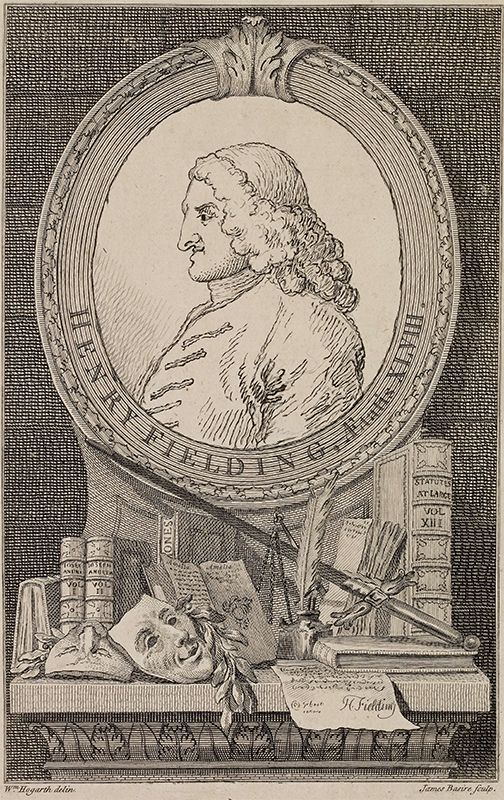

The only authentic portrait of Fielding is from a pen-and-ink sketch by Hogarth, taken from memory, or, according to Murphy, whose account was contradicted by Steevens and Ireland, from a profile cut in paper by a lady. It was engraved by Basire for Murphy's edition of Fielding's works. A miniature occasionally engraved seems to be taken from this. A bust of Fielding has been erected in Taunton shire hall, for which the artist, Miss Margaret Thomas, was guided by Hogarth's drawing. A table, said to have belonged to Fielding at East Stour, was given to the Somersetshire Archæological Society (Notes and Queries, 6th ser. vii. 406).

Fielding never learnt to be prudent. Lady M. W. Montagu compares him to Steele, and speaks of the irresistible buoyancy of spirits which survived his money and his constitution (to Lady Bate, 22 Sept. 1755). No estate could have made him rich. He was more generous than just. The story is often repeated (Gent. Mag. August 1786) that he gave a sum borrowed from Millar, the bookseller, for taxes, to a poorer friend, and that when the tax-gatherer appeared he said: ‘Friendship has called for the money; let the collector call again.’ Murphy says that after he became justice he kept an open table for his poorer friends. The plays represent the recklessness of his youth. From the age of thirty he was struggling vigorously to retrieve his position, to support his family, and to do his duty when in office, and to call attention to grave social evils. This is the period of his great novels, which, however wanting in delicacy, show a sturdy moral sense as well as a masculine insight into life and character. He is beyond question the real founder of the English novel as a genuine picture of men and women, and in some respects has never been surpassed. The famous prophecy of Gibbon, that ‘Tom Jones,’ ‘that exquisite picture of human manners, will survive the palace of the Escurial and the imperial eagle of the house of Austria,’ will be found in his Memoirs (Miscellaneous Works, i. 415). Coleridge's eulogy upon the ‘sunshiny, breezy’ spirit of ‘Tom Jones,’ as contrasted with the ‘hot day-dreamy continuity of Richardson and of “Jonathan Wild,”’ is in his ‘Literary Remains’ (1836, ii. 373). Scott has praised him in his ‘Life,’ and Thackeray in the ‘English Humourists.’ Other criticisms worth notice are in Hazlitt's ‘Comic Writers’ (1819), pp. 222–8; Taine's ‘English Literature’ (by Van Laun), ii. 170–6; Mr. J. R. Lowell's ‘Democracy and other Addresses,’ 1887, pp. 89–105.

The following is a list of Fielding's plays, with first performances, recorded by Genest:

- ‘Love in Several Masques,’ 16 Feb. 1728, Drury Lane.

- ‘The Temple Beau,’ 26 Jan. 1730, Goodman's Fields.

- ‘The Author's Farce and the Pleasures of the Town,’ March 1730, Haymarket (with additions, 19 Jan. 1734, Drury Lane).

- ‘The Coffee-house Politicians, or the Justice caught in his own Trap,’ 4 Dec. 1730, Lincoln's Inn Fields.

- ‘Tom Thumb, a Tragedy,’ afterwards ‘The Tragedy of Tragedies, or the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great,’ Haymarket, 1730, and with additional act, 1731.

- ‘The Grub Street Opera’ (first called ‘The Welsh Opera’), (with this ‘The Masquerade, inscribed to C-t H-d-q-r, by Lemuel Gulliver, Poet Laureate to the King of Lilliput,’ said to have been originally printed in 1728), July 1731, Haymarket.

- ‘The Letter-writers, or a New Way to Keep a Wife at Home,’ 1731, Haymarket.

- ‘The Lottery,’ 1 Jan. 1732, Drury Lane.

- ‘The Modern Husband,’ 21 Feb. 1732, Drury Lane.

- ‘The Covent Garden Tragedy,’ and

- ‘The Debauchees, or the Jesuit Caught,’ 1 June 1732, Drury Lane.

- ‘The Mock Doctor, or the Dumb Lady Cured,’ 8 Sept. 1732, Drury Lane.

- ‘The Miser,’ February 1733, and with ‘Deborah, or a Wife for You All’ (never printed), 6 April 1733, Drury Lane.

- ‘The Intriguing Chambermaid,’ 15 Jan. 1734, Drury Lane

- ‘Don Quixote in England,’ April 1734, Haymarket.

- ‘An Old Man taught Wisdom, or the Virgin Unmasked,’ 6 Jan. 1735, Drury Lane.

- ‘The Universal Gallant, or the Different Husbands,’ 10 Feb. 1735, Drury Lane.

- ‘Pasquin; a Dramatick Satire on the Times, being the rehearsal of two plays, viz. a comedy called “The Election,” and a tragedy called “The Life and Death of Common Sense,”’ April 1736, Haymarket.

- ‘The Historical Register for the Year 1736,’ May 1737, Haymarket.

- ‘Eurydice,’ a farce, 19 May 1737 (printed ‘as it was damned at Drury Lane’).

- ‘Eurydice Hissed, or a Word to the Wise,’ 1737, Haymarket.

- ‘Tumbledown Dick, or Phæthon in the Suds,’ 1737, Haymarket.

- ‘Miss Lucy in Town,’ 5 May 1742, Drury Lane (partly by Fielding), ‘Letter to a Noble Lord … occasioned by representation’ of this, 1742.

- ‘The Wedding Day,’ 17 Feb. 1743, Drury Lane. A German translation of the ‘Wedding Day,’ followed by ‘Eurydice,’ was published at Copenhagen in 1759.

A play called ‘The Fathers, or the Good-natured Man,’ the manuscript of which had been lent to Sir C. Hanbury Williams and lost, was recovered about 1776 by Mr. Johnes, M.P. for Cardigan, and was brought out at Drury Lane 30 Nov. 1798, with a prologue and epilogue by Garrick.

His other works are:

- The ‘Champion’ (with Ralph), collected 1741. Fielding contributed articles from 27 Nov. 1739 to 12 June 1740. Tῆς Ὁμήρου ΥΕΡΝΟΝΙΑΔΟΣ ῥαψωδία ἢ γράμμα α’, The Vernoniad, January 1741; ‘Of True Greatness,’ January 1741 (and in ‘Miscellanies’); ‘The Opposition: a Vision,’ December 1741; ‘The Crisis: a Sermon on Rev. xiv. 9, 10, 11’ (see Nichols, Anecd. viii. 446).

- ‘The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and of his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams,’ February 1742.

- ‘A Full Vindication of the Duchess Dowager of Marlborough,’ 1742.

- ‘Plutus, the God of Riches’ (from Aristophanes), with W. Young, June 1742.

- ‘Miscellanies,’ 3 vols. 1743 (early poems, essays, ‘Journey from this World to the Next,’ and ‘The Life of Mr. Jonathan Wild the Great’).

- Preface to ‘David Simple,’ 1744 (and in 1747); preface to ‘Familiar Letters between the principal characters in David Simple and some others;’ ‘Proper Answer to a Scurrilous Libel by Editor of “Jacobite's Journal,”’ 1747 (defence of Winnington; Lawrence, 225).

- ‘The True Patriot,’ a weekly journal, 5 Nov. 1745 to 10 June 1746.

- ‘The Jacobite's Journal,’ December 1747 to November 1748.

- ‘The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling,’ February 1749.

- ‘A Charge delivered to the Grand Jury … of Westminster,’ 1749.

- ‘A True State of the Case of Bosavern Penlez,’ 1749.

- ‘An Enquiry into the Causes of the late Increase of Robbers, &c., with some Proposals for Remedying this growing Evil,’ January 1751.

- ‘Amelia,’ December 1751.

- ‘The Covent Garden Journal,’ January to November 1752.

- ‘Examples of the Interposition of Providence in the Detection and Punishment of Murder,’ April 1752.

- ‘Proposals for Making an Effectual Provision for the Poor,’ January 1753.

- ‘A Clear State of the Case of Elizabeth Canning,’ March 1753.

- ‘Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon, by the late Henry Fielding,’ with ‘Fragment of a Comment on Lord Bolingbroke's Essays,’ 1755.

The first collective edition, edited by Arthur Murphy, appeared in 1762. A pamphlet called ‘The Cudgel, or a Crabtree Lecture to the author of the Dunciad,’ a satire called ‘The Causidicade,’ and an ‘Apology for the Life of The. Cibber,’ have been erroneously attributed to Fielding. ‘Miscellanies and Poems,’ edited by J. P. Browne, was published in 1872 (supplementary to the standard editions).

[Essay on Life and Genius of Fielding, by Arthur Murphy, prefixed to Works, 1762; Life by Watson, 1807 (no copy in British Museum); Life by Scott in Ballantyne's Novelists' Library, 1821; Life by Roscoe, prefixed to 1840 one vol. edition; Life of Henry Fielding, with Notices of his Writings, his Times, and his Contemporaries, by Frederick Lawrence, 1855; On the Life and Writings of Henry Fielding, by Thomas Keightley, in Fraser's Magazine for January and February 1858; Henry Fielding, by Austin Dobson, in the Men of Letters Series, 1883. Of these the first is perfunctory, vague, and inaccurate. Lawrence was the first to attempt a thorough account. He is criticised in the essays of Mr. Keightley, who contemplated a life. A thorough and exhaustive study by Mr. Austin Dobson gives the only satisfactory investigation of the materials. See also Nichols's Lit. Anecd. iii. 356–85; Biog. Dramatica; Richardson's Correspondence; Hutchins's Dorset, iii. 211 (gives a picture of the house at East Stour); Nichols's Leicestershire, iv. 292, 394 (pedigrees of the Fielding family); Genest's History of the Stage; Cibber's Apology, pp. 231–2; Smith's Nollekens, i. 124–5 (description by Mrs. Hussey); Macklin's Memoirs; Phillimore's Memoirs of Lyttelton (letter to Lyttelton of 29 Aug. 1749); Kilvert's Hurd, p. 45.]

L. S.

Encyclopædia Britannica 11th edition (1911)

FIELDING, HENRY (1707–1754), English novelist and playwright, was born at Sharpham Park, near Glastonbury, Somerset, on the 22nd of April 1707. His father was Lieutenant Edmund Fielding, third son of John Fielding, who was canon of Salisbury and fifth son of the earl of Desmond. The earl of Desmond belonged to the younger branch of the Denbigh family, who, until lately, were supposed to be connected with the Habsburgs. To this claim, now discredited by the researches of Mr J. Horace Round (Studies in Peerage, 1901, pp. 216–249), is to be attributed the famous passage in Gibbon’s Autobiography which predicts for Tom Jones—“that exquisite picture of human manners”—a diuturnity exceeding that of the house of Austria. Henry Fielding’s mother was Sarah Gould, daughter of Sir Henry Gould, a judge of the king’s bench. It is probable that the marriage was not approved by her father, since, though she remained at Sharpham Park for some time after that event, his will provided that her husband should have nothing to do with a legacy of £3000 left her in 1710. About this date the Fieldings moved to East Stour in Dorset. Two girls, Catherine and Ursula, had apparently been born at Sharpham Park; and three more, together with a son, Edmund, followed at East Stour. Sarah, the third of the daughters, born November 1710, and afterwards the author of David Simple and other works, survived her brother.

Fielding’s education up to his mother’s death, which took place in April 1718 at East Stour, seems to have been entrusted to a neighbouring clergyman, Mr Oliver of Motcombe, in whom tradition traces the uncouth lineaments of “Parson Trulliber” in Joseph Andrews. But he must have contrived, nevertheless, to prepare his pupil for Eton, to which place Fielding went about this date, probably as an oppidan. Little is known of his schooldays. There is no record of his name in the college lists; but, if we may believe his first biographer, Arthur Murphy, by no means an unimpeachable authority, he left “uncommonly versed in the Greek authors, and an early master of the Latin classics,”—a statement which should perhaps be qualified by his own words to Sir Robert Walpole in 1730:—

“Tuscan and French are in my head;

Latin I write, and Greek—I read.”

But he certainly made friends among his class-fellows—some of whom continued friends for life. Winnington and Hanbury-Williams were among these. The chief, however, and the most faithful, was George, afterwards Sir George, and later Baron Lyttelton of Frankley.

When Fielding left Eton is unknown. But in November 1725 we hear of him definitely in what seems like a characteristic escapade. He was staying at Lyme (in company with a trusty retainer, ready to “beat, maim or kill” in his young master’s behalf), and apparently bent on carrying off, if necessary by force, a local heiress, Miss Sarah Andrew, whose fluttered guardians promptly hurried her away, and married her to some one else (Athenaeum, 2nd June 1883). Her baffled admirer consoled himself by translating part of Juvenal’s sixth satire into verse as “all the Revenge taken by an injured Lover.” After this he must have lived the usual life of a young man about town, and probably at this date improved the acquaintance of his second cousin, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, to whom he inscribed his first comedy, Love in Several Masques, produced at Drury Lane in February 1728. The moment was not particularly favourable, since it succeeded Cibber’s Provok’d Husband, and was contemporary with Gay’s popular Beggar’s Opera. Almost immediately afterwards (March 16th) Fielding entered himself as “Stud. Lit.” at Leiden University. He was still there in February 1729. But he had apparently left before the annual registration of February 1730, when his name is absent from the books (Macmillan’s Magazine, April 1907); and in January 1730 he brought out a second comedy at the newly-opened theatre in Goodman’s Fields. Like its predecessor, the Temple Beau was an essay in the vein of Congreve and Wycherley, though, in a measure, an advance on Love in Several Masques.

With the Temple Beau Fielding’s dramatic career definitely begins. His father had married again; and his Leiden career had been interrupted for lack of funds. Nominally, he was entitled to an allowance of £200 a year; but this (he was accustomed to say) “any body might pay that would.” Young, handsome, ardent and fond of pleasure, he began that career as a hand-to-mouth playwright around which so much legend has gathered—and gathers. Having—in his own words—no choice but to be a hackney coachman or a hackney writer, he chose the pen; and his inclinations, as well as his opportunities, led him to the stage. From 1730 to 1736 he rapidly brought out a large number of pieces, most of which had merit enough to secure their being acted, but not sufficient to earn a lasting reputation for their author. His chief successes, from a critical point of view, the Author’s Farce (1730) and Tom Thumb (1730, 1731), were burlesques; and he also was fortunate in two translations from Molière, the Mock Doctor (1732) and the Miser (1733). Of the rest (with one or two exceptions, to be mentioned presently) the names need only be recorded. They are The Coffee-House Politician, a comedy (1730); The Letter Writers, a farce (1731); The Grub-Street Opera, a burlesque (1731); The Lottery, a farce (1732); The Modern Husband, a comedy (1732); The Covent Garden Tragedy, a burlesque (1732); The Old Debauchees, a comedy (1732); Deborah; or, a Wife for you all, an after-piece (1733); The Intriguing Chambermaid (from Regnard), a two-act comedy (1734); and Don Quixote in England, a comedy, which had been partly sketched at Leiden.

Don Quixote was produced in 1734, and the list of plays may be here interrupted by an event of which the date has only recently been ascertained, namely, Fielding’s first marriage. This took place on the 28th of November 1734 at St Mary, Charlcornbe, near Bath (Macmillan’s Magazine, April 1907), the lady being a Salisbury beauty, Miss Charlotte Cradock, of whom he had been an admirer, if not a suitor, as far back as 1730. This is a fact which should be taken into consideration in estimating the exact Bohemianism of his London life, for there is no doubt that he was devotedly attached to her. After a fresh farce entitled An Old Man taught Wisdom, and the comparative failure of a new comedy, The Universal Gallant, both produced early in 1735, he seems for a time to have retired with his bride, who came into £1500, to his old home at East Stour. Around this rural seclusion fiction has freely accreted. He is supposed to have lived for three years on the footing of a typical 18th-century country gentleman; to have kept a pack of hounds; to have put his servants into impossible yellow liveries; and generally, by profuse hospitality and reckless expenditure, to have made rapid duck and drake of Mrs Fielding’s modest legacy. Something of this is demonstrably false; much, grossly exaggerated. In any case, he was in London as late as February 1735 (the date of the “Preface” to The Universal Gallant); and early in March 1736 he was back again managing the Haymarket theatre with a so-called “Great Mogul’s Company of English Comedians.”

Upon this new enterprise fortune, at the outset, seemed to smile. The first piece (produced on the 5th of March) was Pasquin, a Dramatick Satire on the Times (a piece akin in its plan to Buckingham’s Rehearsal), which contained, in addition to much admirable burlesque, a good deal of very direct criticism of the shameless political corruption of the Walpole era. Its success was unmistakable; and when, after bringing out the remarkable Fatal Curiosity of George Lillo, its author followed up Pasquin by the Historical Register for the Year 1736, of which the effrontery was even more daring than that of its predecessor, the ministry began to bethink themselves that matters were going too far. How they actually effected their object is obscure: but grounds were speedily concocted for the Licensing Act of 1737, which restricted the number of theatres, rendered the lord chamberlain’s licence an indispensable preliminary to stage representation, and—in a word—effectually put an end to Fielding’s career as a dramatist.

Whether, had that career been prolonged to its maturity, the result would have enriched the theatrical repertoire with a new species of burlesque, or reinforced it with fresh variations on the “wit-traps” of Wycherley and Congreve, is one of those inquiries that are more academic than, profitable. What may be affirmed is, that Fielding’s plays, as we have them, exhibit abundant invention and ingenuity; that they are full of humour and high spirits; that, though they may have been hastily written, they were by no means thoughtlessly constructed; and that, in composing them, their author attentively considered either managerial hints, or the conditions of the market. Against this, one must set the fact that they are often immodest; and that, whatever their intrinsic merit, they have failed to rival in permanent popularity the work of inferior men. Fielding’s own conclusion was, “that he left off writing for the stage, when he ought to have begun”—which can only mean that he himself regarded his plays as the outcome of imitation rather than experience. They probably taught him how to construct Tom Jones; but whether he could ever have written a comedy at the level of that novel, can only be established by a comparison which it is impossible to make, namely, a comparison with Tom Jones of a comedy written at the same age, and in similar circumstances.

Tumble-Down Dick; or, Phaeton in the Suds, Eurydice and Eurydice hissed are the names of three occasional pieces which belong to the last months of Fielding’s career as a Haymarket manager. By this date he was thirty, with a wife and daughter. As a means of support, he reverted to the profession of his maternal grandfather; and, in November 1737, he entered the Middle Temple, being described in the books of the society as “of East Stour in Dorset.” That he set himself strenuously to master his new profession, is admitted; though it is unlikely that he had entirely discarded the irregular habits which had grown upon him in his irresponsible bachelorhood. He also did a good deal of literary work, the best known of which is contained in the Champion, a “News-Journal” of the Spectator type undertaken with James Ralph, whose poem of “Night” is made notorious in the Dunciad. That the Champion was not without merit is undoubted; but the essay-type was for the moment out-worn, and neither Fielding nor his coadjutor could lend it fresh vitality. Fielding contributed papers from the 15th of November 1739 to the 19th of June 1740. On the 20th of June he was called to the bar, and occupied chambers in Pump Court. It is further related that, in the diligent pursuit of his calling, he travelled the Western Circuit, and attended the Wiltshire sessions.

Although, with the Champion, he professed, for the time, to have relinquished periodical literature, he still wrote at intervals, a fact which, taken in connexion with his past reputation as an effective satirist, probably led to his being “unjustly censured” for much that he never produced. But he certainly wrote a poem “Of True Greatness” (1741); a first book of a burlesque epic, the Vernoniad, prompted by Vernon’s expedition of 1739; a vision called the Opposition, and, perhaps, a political sermon entitled the Crisis (1741). Another piece, now known to have been attributed to him by his contemporaries (Hist. MSS. Comm., Rept. 12, App. Pt. ix., p. 204), is the pamphlet entitled An Apology for the Life of Mrs Shamela Andrews, a clever but coarse attack upon the prurient side of Richardson’s Pamela, which had been issued in 1740, and was at the height of its popularity. Shamela followed early in 1741. Richardson, who was well acquainted with Fielding’s four sisters, at that date his neighbours at Hammersmith, confidently attributed it to Fielding (Corr. 1804, iv. 286, and unpublished letter at South Kensington); and there are suggestive points of internal evidence (such as the transformation of Pamela’s “MR B.” into “Mr Booby”) which tend to connect it with the future Joseph Andrews. Fielding, however, never acknowledged it, or referred to it; and a great deal has been laid to his charge that he never deserved (“Preface” to Miscellanies, 1743).

But whatever may be decided in regard to the authorship of Shamela, it is quite possible that it prompted the more memorable Joseph Andrews, which made its appearance in February 1742, and concerning which there is no question. Professing, on his title-page, to imitate Cervantes, Fielding set out to cover Pamela with Homeric ridicule by transferring the heroine’s embarrassments to a hero, supposed to be her brother. Allied to this purpose was a collateral attack upon the slipshod Apology of the playwright Colley Cibber, with whom, for obscure reasons, Fielding had long been at war. But the avowed object of the book fell speedily into the background as its author warmed to his theme. His secondary speedily became his primary characters, and Lady Booby and Joseph Andrews do not interest us now as much as Mrs Slipslop and Parson Adams—the latter an invention that ranges in literature with Sterne’s “Uncle Toby” and Goldsmith’s “Vicar.” Yet more than these and others equally admirable in their round veracity, is the writer’s penetrating outlook upon the frailties and failures of human nature. By the time he had reached his second volume, he had convinced himself that he had inaugurated a new fashion of fiction; and in a “Preface” of exceptional ability, he announced his discovery. Postulating that the epic might be “comic” or “tragic,” prose or verse, he claimed to have achieved what he termed the “Comic Epos in Prose,” of which the action was “ludicrous” rather than “sublime,” and the personages selected from society at large, rather than the restricted ranks of conventional high life. His plan, it will be observed, was happily adapted to his gifts of humour, satire, and above all, irony. That it was matured when it began may perhaps be doubted, but it was certainly matured when it ended. Indeed, except for the plot, which, in his picaresque first idea, had not preceded the conception, Joseph Andrews has all the characteristics of Tom Jones, even (in part) to the initial chapters.

Joseph Andrews had considerable success, and the exact sum paid for it by Andrew Millar, the publisher, according to the assignment now at South Kensington, was £183:11s., one of the witnesses being the author’s friend, William Young, popularly supposed to be the original of Parson Adams. It was with Young that Fielding undertook what, with exception of “a very small share” in the farce of Miss Lucy in Town (1742), constituted his next work, a translation of the Plutus of Aristophanes, which never seems to have justified any similar experiments. Another of his minor works was a Vindication of the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough (1742), then much before the public by reason of the Account of her Life which she had recently put forth. Later in the same year, Garrick applied to Fielding for a play; and a very early effort, The Wedding Day, was hastily patched together, and produced at Drury Lane in February 1743 with no great success. It was, however, included in Fielding’s next important publication, the three volumes of Miscellanies issued by subscription in the succeeding April. These also comprised some early poems, some essays, a Lucianic fragment entitled a Journey from this World to the Next, and, last but not least, occupying the entire final volume, the remarkable performance entitled the History of the Life of the late Mr Jonathan Wild the Great.

It is probable that, in its composition, Jonathan Wild preceded Joseph Andrews. At all events it seems unlikely that Fielding would have followed up a success in a new line by an effort so entirely different in character. Taking for his ostensible hero a well-known thief-taker, who had been hanged in 1725, he proceeds to illustrate, by a mock-heroic account of his progress to Tyburn, the general proposition that greatness without goodness is no better than badness. He will not go so far as to say that all “Human Nature is Newgate with the Mask on”; but he evidently regards the description as fairly applicable to a good many so-called great people. Irony (and especially Irony neat) is not a popular form of rhetoric; and the remorseless pertinacity with which Fielding pursues his demonstration is to many readers discomforting and even distasteful. Yet—in spite of Scott—Jonathan Wild has its softer pages; and as a purely intellectual conception it is not surpassed by any of the author’s works.

His actual biography, both before and after Jonathan Wild, is obscure. There are evidences that he laboured diligently at his profession; there are also evidences of sickness and embarrassment. He had become early a martyr to the malady of his century—gout, and the uncertainties of a precarious livelihood told grievously upon his beautiful wife, who eventually died of fever in his arms, leaving him for the time so stunned and bewildered by grief that his friends feared for his reason. For some years his published productions were unimportant. He wrote “Prefaces” to the David Simple of his sister Sarah in 1744 and 1747; and, in 1745–1746 and 1747–1748, produced two newspapers in the ministerial interest, the True Patriot and the Jacobite’s Journal, both of which are connected with, or derive from, the rebellion of 1745, and were doubtless, when they ceased, the pretext of a pension from the public service money (Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon, “Introduction”). In November 1747 he married his wife’s maid, Mary Daniel, at St Bene’t’s, Paul’s Wharf; and in December 1748, by the interest of his old school-fellow, Lyttelton, he was made a principal justice of peace for Middlesex and Westminster, an office which put him in possession of a house in Bow Street, and £300 per annum “of the dirtiest money upon earth” (ibid.), which might have been more had he condescended to become what was known as a “trading” magistrate.

For some time previously, while at Bath, Salisbury, Twickenham and other temporary resting-places, he had intermittently occupied himself in composing his second great novel, Tom Jones; or, the History of a Foundling. For this, in June 1748, Millar had paid him £600, to which he added £100 more in 1749. In the February of the latter year it was published with a dedication to Lyttelton, to whose pecuniary assistance to the author during the composition it plainly bears witness. In Tom Jones Fielding systematically developed the “new Province of Writing” he had discovered incidentally in Joseph Andrews. He paid closer attention to the construction and evolution of the plot; he elaborated the initial essays to each book which he had partly employed before, and he compressed into his work the flower and fruit of his forty years’ experience of life. He has, indeed, no character quite up to the level of Parson Adams, but his Westerns and Partridges, his Allworthys and Blifils, have the inestimable gift of life. He makes no pretence to produce “models of perfection,” but pictures of ordinary humanity, rather perhaps in the rough than the polished, the natural than the artificial, and his desire is to do this with absolute truthfulness, neither extenuating nor disguising defects and shortcomings. One of the results of this unvarnished naturalism has been to attract more attention to certain of the episodes than their inventor ever intended. But that, in the manners of his time, he had chapter and verse for everything he drew is clear. His sincere purpose was, he declared, “to recommend goodness and innocence,” and his obvious aversions are vanity and hypocrisy. The methods of fiction have grown more sophisticated since his day, and other forms of literary egotism have taken the place of his once famous introductory essays, but the traces of Tom Jones are still discernible in most of our manlier modern fiction.

Meanwhile, its author was showing considerable activity in his magisterial duties. In May 1749, he was chosen chairman of quarter sessions for Westminster; and in June he delivered himself of a weighty charge to the grand jury. Besides other pamphlets, he produced a careful and still readable Enquiry into the Causes of the late Increase of Robbers, &c. (1751), which, among its other merits, was not ineffectual in helping on the famous Gin Act of that year, a practical result to which the “Gin Lane” and “Beer Street” of his friend Hogarth also materially contributed. These duties and preoccupations left their mark on his next fiction, Amelia (1752), which is rather more taken up with social problems and popular grievances than its forerunners. But the leading personage, in whom, as in the Sophia Western of Tom Jones, he reproduced the traits of his first wife, is certainly, as even Johnson admitted, “the most pleasing heroine of all the romances.” The minor characters, too, especially Dr Harrison and Colonel Bath, are equal to any in Tom Jones. The book nevertheless shows signs, not of failure but of fatigue, perhaps of haste—a circumstance heightened by the absence of those “prolegomenous” chapters over which the author had lingered so lovingly in Tom Jones. In 1749 he had been dangerously ill, and his health was visibly breaking. The £1000 which Millar is said to have given for Amelia must have been painfully earned.

Early in 1752 his still indomitable energy prompted him to start a third newspaper, the Covent Garden Journal, which ran from the 4th of January to the 25th of November. It is an interesting contemporary record, and throws a good deal of light on his Bow Street duties. But it has no great literary value, and it unhappily involved him in harassing and undignified hostilities with Smollett, Dr John Hill, Bonnell Thornton and other of his contemporaries. To the following year belong pamphlets on “Provision for the Poor,” and the case of the strange impostor, Elizabeth Canning (1734–1773).[1] By 1754 his own case, as regards health, had grown desperate; and he made matters worse by a gallant and successful attempt to break up a “gang of villains and cut-throats,” who had become the terror of the metropolis. This accomplished, he resigned his office to his half-brother John (afterwards Sir John) Fielding. But it was now too late. After fruitless essay both of Dr Ward’s specifics and the tar-water of Bishop Berkeley, it was felt that his sole chance of prolonging life lay in removal to a warmer climate. On the 26th of June 1754 he accordingly left his little country house at Fordhook, Ealing, for Lisbon, in the “Queen of Portugal,” Richard Veal master. The ship, as often, was tediously wind-bound, and the protracted discomforts of the sick man and his family are narrated at length in the touching posthumous tract entitled the Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon, which, with a fragment of a comment on Bolingbroke’s then recently issued essays, was published in February 1755 “for the Benefit of his [Fielding’s] Wife and Children.” Reaching Lisbon at last in August 1754, he died there two months later (8th October), and was buried in the English cemetery, where a monument was erected to him in 1830. Luget Britannia gremio non dari fovere natum is inscribed upon it.

His estate, including the proceeds of a fair library, only covered his just debts (Athenaeum, 25th Nov. 1905); but his family, a daughter by his first, and two boys and a girl by his second wife, were faithfully cared for by his brother John, and by his friend Ralph Allen of Prior Park, Bath, the Squire Allworthy of Tom Jones. His will (undated) was printed in the Athenaeum for the 1st of February 1890. There is but one absolutely authentic portrait of him, a familiar outline by Hogarth, executed from memory for Andrew Millar’s edition of his works in 1762. It is the likeness of a man broken by ill-health, and affords but faint indication of the handsome Harry Fielding who in his salad days “warmed both hands before the fire of life.” Far too much stress, it is now held, has been laid by his first biographers upon the unworshipful side of his early career. That he was always profuse, sanguine and more or less improvident, is as probable as that he was always manly, generous and sympathetic. But it is also plain that, in his later years, he did much, as father, friend and magistrate, to redeem the errors, real and imputed, of a too-youthful youth.

As a playwright and essayist his rank is not elevated. But as a novelist his place is a definite one. If the Spectator is to be credited with foreshadowing the characters of the novel, Defoe with its earliest form, and Richardson with its first experiments in sentimental analysis, it is to Henry Fielding that we owe its first accurate delineation of contemporary manners. Neglecting, or practically neglecting, sentiment as unmanly, and relying chiefly on humour and ridicule, he set out to draw life precisely as he saw it around him, without blanks or dashes. He was, it may be, for a judicial moralist, too indulgent to some of its frailties, but he was merciless to its meaner vices. For reasons which have been already given, his high-water mark is Tom Jones, which has remained, and remains, a model in its way of the kind he inaugurated.

An essay on Fielding’s life and writings is prefixed to Arthur Murphy’s edition of his works (1762), and short biographies have been written by Walter Scott and William Roscoe. There are also lives by Watson (1807), Lawrence (1855), Austin Dobson (“Men of Letters,” 1883, 1907) and G. M. Godden (1909). An annotated edition of the Journal of a Voyage to Lisbon is included in the “World’s Classics” (1907). (A. D.)