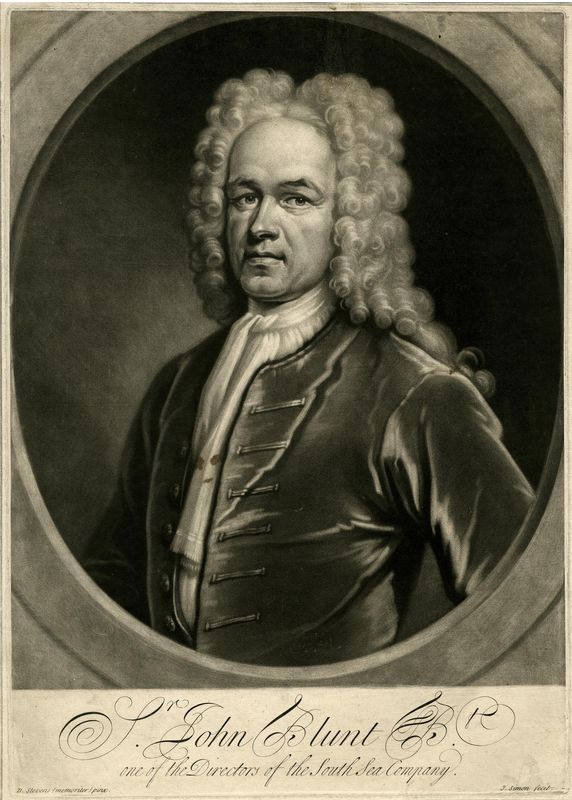

Sir John Blunt (1665–1733)

Pat Rogers, University of South Florida

October 2022

John Blunt helped to ruin a great many lives, but posterity has revenged the losses he caused in the great Bubble of 1720 by neglecting to provide a full account of his own life. A complete biography might palliate some of the charges against him, but the bare facts would remain. He was the principal architect of the financial disaster, first when he played a leading part in the foundation of the South Sea Company, and second when he supervised its reckless expansion prior to the great crash.

The setting for most of Blunt’s story is easy to identify. Around 1720, a small web of streets off Cornhill, in the heart of the City of London, achieved notoriety as the focus of attention for anyone trying to make sense of giddy fluctuations in the stock market. The main feature locally was the Royal Exchange, an impressive building surmounted by a tall tower, erected in 1669 after the Great Fire to house the commercial centre originally founded by Sir Thomas Gresham in the Elizabethan era. It backed on to Threadneedle Street, a few years later to become the home of the Bank of England. Across the road lay the entrance to Exchange Alley, a narrow lane that zigzagged down to Lombard Street, emerging close to the site of Lloyd’s coffee house, where modern insurance had begun to develop, and further along the General Post Office, headquarters of London mail operations from 1678 to 1829. Nearby, Birchin Lane ran an almost parallel course on a straighter line. The area was populated by a host of coffee shops, where jobbers traded shares in close proximity to bankers and insurance offices. “The whole maze, with its six entries (two in Lombard Street, two in Cornhill, and two in Birchin Lane) … covered an area rather smaller than a football pitch” (John Carswell). Effectively, this patch of ground supplied the neural network that powered the Financial Revolution taking place in the capital since the 1690s. It was here in Birchin Lane that John Blunt set up shop as a banker and maintained his lavish home.

The son of a shoemaker from Kent, he came from a Baptist family. His own baptism took place in Rochester on 24 July 1665. According to Pope, "He was a Dissenter of a most religious deportment, and profess'd to be a great believer. Moving to the capital, he was apprenticed to a scrivener in Holborn, an occupation that, to cite Carswell once more, combined the work of “the solicitor, the estate agent, and the business agency of that enterprising age.” In March 1689 he was admitted to the freedom of the powerful Merchant Taylors Company, as the first step in his gradual rise through the charmed circle of financial professionals in the City. He now felt secure enough to marry Elizabeth Court on 16 July of the same year: she bore him seven children prior to her death in 1708. Blunt married Sarah Tudman as his second wife; he may have outlived his philoprogenitive urges, because they had no offspring. Before the end of the century, he became a parishioner of St. Michael’s, Cornhill, a church that appropriately stood near the top of Birchin Lane.

Already the young man seems to have dreamt of conquering London, utilising those resources, physical and human, that lay close at hand. The key event in his rise came when he was appointed secretary of the Sword Blade Company in 1703. This was an organisation that had been set up to make hollow blades by a well known projector named Sir Stephen Evance, whose business as a goldsmith (effectively, banker) in Lombard Street failed spectacularly in 1711, leading to his suicide. The company had come into the hands of three individuals whom Daniel Defoe would later term “the three Capital Sharpers of Great Britain,” namely George Caswall and Elias Turner along with Blunt. They shifted the firm’s operations to buying up the forfeited estate of Jacobites in Ireland, but this proved unremunerative. A more momentous switch occurred when the Sword Blade turned itself into a bank, providing loans to the government in competition with the Bank of England, itself a relatively new creation but already a key player in the national system of credit.

It was Blunt, assisted by Caswall, who persuaded Robert Harley, first Earl of Oxford to set up the South Sea Company in 1711 and who drafted its charter. Harley had just come into power at the head of a Tory government: he was appointed governor of the new company, and the directors included the secretary of state, Henry St. John (later Lord Bolingbroke), as well as Blunt and Caswall. These two had helped to manage a successful lottery on behalf of the ministry, and as a result the main Sword Blade function became that of banker to South Sea, if not something close to a wholly owned subsidiary, bearing in mind the overlap in its key offices with the managers of the new Company. The aims of the government in founding the institution were in large measure political, to curb the influence of the aggressively Whig Bank of England. Its chief function was to take the huge unsecured debt of the nation, although moderately realistic hopes were held out for lucrative trade with Spanish America, especially after Britain gained the contract to transport slaves across the Atlantic for thirty years in the Utrecht peace treaty of 1713 that ended the long-running War of the Spanish Succession. In the end, the Company sent out relatively few ships in its early years, and they were not all profitable.

This mattered less because, despite its title, the trading arm of the South Sea Company was only a secondary part of the operation. Blunt was behind a scheme in 1719 to take over the entire national debt, which meant among other things ousting the Bank of England and the East India Company from their former privileged monopoly role in state finance. To achieve this, the Company had to promise an unsustainable rate of return to the government. A series of money subscriptions garnered a flow of new cash into its coffers, and a number of loans were taken out, but the outlay could only be afforded with a steady appreciation in the price of stock. This happened for some time: the price went up from around 125 at the start of 1720 to reach dizzying levels by the summer, touching 1,000 in early August, just when subscription payments became due. This was the high point, and once the reaction set in the fall was precipitous; within weeks the price went down to its January levels. The results are predictable and well known. A large collection of investors lost everything. There were scenes of panic in Exchange Alley and surrounding streets. Embarrassing revelations came out to show that members of the government—including the chancellor of the exchequer and a senior treasury official—and even the royal family had benefitted from sweet deals. Bribes were uncovered, and creative bookkeeping exposed that had served to mask the true state of Company finances. The fall led to the collapse of a government led by Lord Sunderland and Lord Stanhope. Both were dead within two years, and the salvage plan of Robert Walpole brought him to a political dominance he would not relinquish for two decades.

Meanwhile the most obviously guilty men, especially those without the right connections, were hung up to dry. A parliamentary committee examined their finances, and levied a fine commensurate with their assets and the degree of their imputed guilt. Blunt could not have expected to get away lightly. When the South Sea project was riding high, he had become a celebrity, and he was even awarded a baronetcy in 1719. A year later, after the collapse of the Bubble, he naturally attracted intense public dislike. He was grilled by the committee of inquiry, as their most important witness, and obliged to reveal compromising facts, such as the gift of tranches of South Sea stock to the mistresses of George I. Branded as "the chief contriver and promoter of all the mischief," he was forced to sacrifice his estate of close to £200,000, except for a comparatively slender residue of £5,000. (Walpole wanted to allow him to keep just ₤1,000.) Some figures published in the press show him paying just under £50,000 for stock in March 1720 and receiving more than £275,000. He attempted to conceal £50,000 of his assets by means of a fraudulent conveyance to the corrupt businessman John Ward. The scheme was detected, but Blunt was pardoned after revealing its nature. He continued to defend himself vigorously for the remainder of his life, suggesting that much of the opprobrium should be directed at the Bank of England for its role in fomenting speculation—a claim without much merit. He died at Bath on 23 January 1733. Somehow he contrived to leave members of his family legacies valued at £13,000.

He has been bequeathed one enduring legacy within the realms of literature. This comes in Alexander Pope’s Epistle to Bathurst (1733), the greatest poetic meditation on South Sea. The passage here about the projector clearly presents Blunt as a rogue on a massive scale, yet there is a measure of understanding and a sense that Blunt may have been a scapegoat used to protect the skin of others equally guilty. Like other projectors of the age, Blunt possessed a certain originality of mind and a capacity to see future possibilities that others missed. However, he lacked self-knowledge, and his arrogance made it impossible for him to acknowledge mistakes. A good summary is that of Howard Erskine-Hill: “John Blunt was a tirelessly energetic and ambitious man with a highly developed and hectic sense of competition, an impatient capacity to grasp at new and startling possibilities, though not always fully to understand them.” He thus fitted exactly what the age demanded. The tempest that was South Sea collected into itself the vices, but also some of the virtues, of the historical climate in which it formed. Its strength derived from a restless energy, a hunger to grasp every stray opportunity, an intensely competitive atmosphere, a quest for new initiatives in unexpected places, as well as a lack of circumspection and clear preliminary thought. The outcome was a hectic season of financial turmoil, political agitation and social unrest. For that, Blunt must take a large share of the blame.

In the absence of a comprehensive biography, the most searching account by far of Blunt’s career is Howard Erskine-Hill’s chapter “Much Injur’d Blunt,” in The Social Milieu of Alexander Pope (New Haven, 1975), 166–203.