Peter Williamson (1730–1799)

Dana Lew, University of Toronto

February 2025

Peter Williamson was a Scottish author, publisher, colonial soldier, entrepreneur, and storyteller best known for his dubious account of escaping Indigenous captivity in North America. The popularity of his captivity narrative, French and Indian Cruelty; Exemplified in the Life and Various Vicissitudes of Fortune of Peter Williamson (1757), made him a minor celebrity in Britain and earned him the moniker “Indian Peter.” Declaring himself “King of the Indians,” Williamson capitalized on public interest in colonial-Indigenous conflict at the height of the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). He travelled across the British Isles, publishing new editions of his narrative in York (1758), Glasgow (1758), London (1759), Edinburgh (1762), and Dublin (1766), and giving live performances to paying customers in exoticized dress. His dramatic impersonation of his “savage” Lenape (or Delaware) captors, their war dances, and how they scalped, tomahawked, and gruesomely tortured their enemies attracted some controversy, but not for the reasons we might assume. It was Williamson’s claim that he was kidnapped as a child in Aberdeen and sold into colonial indenture that drew the ire of Aberdeen magistrates when he returned home. Arrested for libel, Williamson was branded a liar and banished from the city in 1758. The redeemed captive was forced to fight for his freedom once again.

This time he took his battle to court, suing the Aberdeen magistrates and subsequently the merchants who invested in his voyage to America. To prove his innocence, Williamson spent the next ten years collecting evidence about his early life in Aberdeenshire and the Aberdeen servant trade during the 1740s. He tells us in the fifth Edinburgh edition of French and Indian Cruelty (1762) that “I was born in Hirnley, in the parish of Aboyne and county of Aberdeen, North-Britain; if not of rich, yet of reputable parents, who supported me in the best manner they could.” After being sent to live with his aunt in Aberdeen, on a fateful day by the quay Williamson was kidnapped by “two fellows belonging to a vessel in the harbour, employed (as the trade then was), by some of the worthy merchants of the town.” In his attempt to expose the corruption of Aberdeen’s leading citizens profiting from the trade in kidnapped youths, cracks in Williamson’s story begin to appear. He had previously claimed in the first York edition to have been eight years old when he was kidnapped and twenty-eight years old at the time of the book’s 1757 publication, dating the kidnapping to 1737. But these dates were inconsistent with the departure of the Planter, the ship that carried Williamson to North America, which sailed from Aberdeen in May 1743. As it turned out, Williamson had exaggerated his youth. A key attestation from Aboyne parish minister Reverend William Forsyth revealed that on 15 February 1730, “James Williamson in Hirnley had his son baptized in face of the Congregation Called Peter.” He was in fact thirteen and not eight when he sailed on the Planter. Only in the fifth edition did Williamson concede his falsehood by removing the reference to being “eight Years of age” from the title page and altering the language of the kidnapping to the less specific “when under the years of pupillarity.” Still, thirteen was under the legal age of consent for an indenture, meaning that the baptism certificate paid off handsomely for Williamson in court. The Scottish Court of Session awarded him £100 in 1762 and a further £200 in 1768, which by some measures would equal more than £50,000 today. Williamson’s legal victories against the Aberdeen magistrates and merchants vindicated his reputation, lending credence to French and Indian Cruelty and his adventures in North America.

Of course, Williamson’s story of captivity, escape, and revenge against his former Lenape captors is, according to historian Timothy J. Shannon, “without a doubt a bald-faced lie.” But there are still elements of truth to his tall tale. For instance, near the end of his Atlantic crossing Williamson relates that “above twelve o’clock at night the ship struck on a sand bank, off Cape May, near the capes of Delaware, and to the great terror and affright of the ship’s company, in a small time, was almost full of water.” The captives and crew were forced to encamp on an island for “near three weeks” until “we were taken in by a vessel bound to Philadelphia.” Remarkably, the Planter’s shipwreck à la Robinson Crusoe is corroborated by several sources, including a newspaper notice in the Pennsylvania Gazette from 28 July 1743 that matches the ship’s departure date and Williamson’s estimation that they spent “eleven weeks” at sea. When Williamson arrives in Philadelphia, however, his lies intensify. He asserts that he was sold to “one of my countrymen, whose name was Hugh Wilson, a North-Britain [sic.], for the term of seven years,” who came to America in similar circumstances as a youth, “having been kidnapped from St. Johnston in Scotland.” Williamson describes his master as benevolent, bestowing £200 in Pennsylvania currency on his indentured servant, which Williamson uses to marry “the daughter of a substantial planter” and settle down in a 200-acre property on the Pennsylvania frontier. All these elements of the narrative appear to be fabricated. There is no record of a Hugh Wilson from Scotland or of Williamson owning property in Pennsylvania.

Williamson’s freedom did not last long. On 2 October 1754, Lenape raiders kidnapped him, set fire to his home, and tortured him in excruciating fashion by “taking the burning coals and sticks, flaming with fire at the ends, [and] holding them near my face, head, hands, and feet, with a deal of monstrous pleasure and satisfaction.” Williamson remained their prisoner—witnessing numerous instances of “savage” cruelty—for three months as the party travelled south along the Susquehanna River until he managed to escape on 4 January 1755. Shannon debunks Williamson’s captivity since it takes place at a time of peace between the Lenape and Pennsylvania settlers. Williamson seems to have compiled fragments from colonial newspapers that printed stories of Lenape raids on the Pennsylvania frontier. Thus, the gruesome murders reported in the text (the families of Jacob Snider, burned and scalped; John Adams, whose wife is killed and her dead body raped; John Lewis, Jacob Miller, and George Folke, all burned and scalped; an unnamed captive tortured by having his brains boiled until “his Eyes gush’d out of their Sockets”) all seem to be Williamson’s invention. After his escape, Williamson enlists in the British army to take revenge against his former captors. The “savage” cruelty with which he and his fellow soldiers massacre a Lenape war party, killing “every Man of them” and fighting over the spoils by “cutting, hacking, and scalping the dead Indians,” anticipates later accounts of the colonial frontier by Robert Eastburn (1758) and Henry Grace (1764) where British soldiers mimic the violence of their demonized Indigenous counterparts. Perhaps the only truthful aspect of this phase of Williamson’s narrative comes when he is once again taken captive, this time as a French prisoner of war at the Battle of Fort Oswego (1756). After being marched to Canada, he claims to have been one of 500 Oswego prisoners put aboard La Renommé, which sailed from Québec and arrived in Plymouth in 1757. Discharged from the British army because of a wounded hand, Williamson returned home a changed man. He was now “Indian Peter,” the redeemed captive and Indigenous-pseudo expert with stories to tell.

Williamson toured the British Isles as he fought his legal battles over a ten-year span. Magazines and newspapers in London and Edinburgh circulated excerpts from French and Indian Cruelty and advertisements for his live shows. One such advert in the Edinburgh Evening Courant from 7 October 1758 stated that Williamson’s performance was reserved for six or more people because “going through the different ceremonies and manners of the Savages is very laborious.” He performed antic dances and war whoops, showcased tomahawks and scalping knives, and promoted his narrative by selling new editions augmented with extracts from the court cases. By June 1760 the success of Williamson’s story had earned him enough money to open a coffeehouse in the heart of Edinburgh. Known as the “American Coffeehouse,” it was a venue in which he displayed American exotica and sold copies of his book, exploiting his crude representation of Indigenous Americans for social and financial gain. He opened a second coffeehouse inside Parliament House in 1767, which is memorialized in Robert Fergusson’s poem, The Rising of the Session (1773):

This vacance is a heavy doom

On Indian Peter’s coffee-room,

For a’ his china pigs are toom;

Nor do we see

In wine the soukar [sugar] biskets soom [swim]

As light’s a flee.

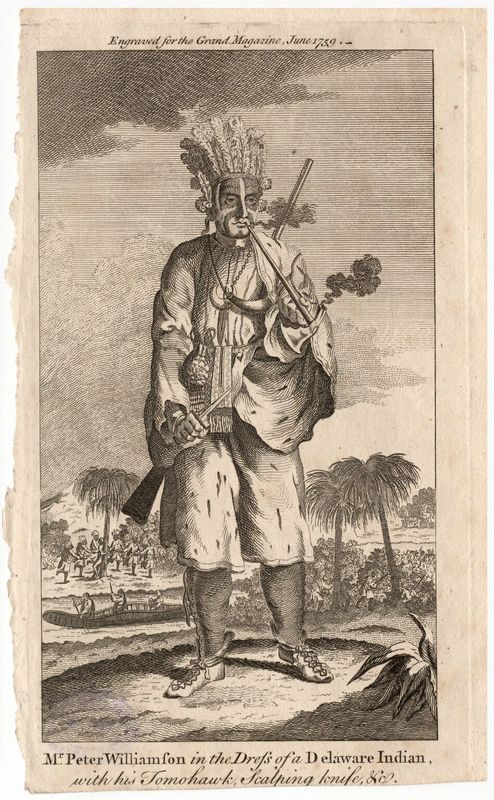

Williamson’s fraught legacy is best illustrated by the frontispiece to French and Indian Cruelty (see above), an exotic fabrication of Indigeneity that lived on in various forms until his death in 1799. The image first appeared in London’s Grand Magazine for 30 June 1759 and was widely circulated thereafter. By 1766 in Dublin, the same year that Williamson promoted his seventh Dublin edition of French and Indian Cruelty after a sixth fraudulent edition had been printed in the city, a translation of Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix’s A Voyage to North America featured the frontispiece of “A Delaware Indian, with his Tomohawk, Scalping knife, &c,” an image that mirrored Williamson’s original. It appears that the Charlevoix printers traced Williamson’s engraving to create this duplicate, mistaking Williamson for a Lenape. Pabineau Mi’kmaw scholar Robbie Richardson identifies similar copies of the engraving in A Collection of the Dresses of Different, Nations, Antient and Modern (1772) and A New Moral System of Geography (1790) and aptly concludes that “though he could never become one in life despite his desire to, Williamson circulated in print as a genuine Indian.”

Williamson also started Edinburgh’s first penny post where he published the city’s first directory (1773) and the short-lived Scots Spy magazine (1776–1777). Yet nothing could eclipse his captivity narrative and status as “King of the Indians.” John Kay’s dual portrait, Travells Eldest Son in Conversation with a Cherokee Chief (1791), depicts Williamson pointing his finger at fellow traveller James Bruce of Kinnaird and questioning the veracity of Bruce’s travelogue. Kay misidentifies Williamson as a “Cherokee chief,” an error to which Williamson later alludes in his satirical handbill, Royal Abdication (1792). In keeping with French revolutionaries who intend to “extirpate the Name and Race of KINGS from the face of the earth,” Williamson announces his abdication from the North American throne and promises to only sell alcohol “of the true Cherokee flavour,” which are “Stimulants to British patriotism, social intercourse, and domestic happiness.” Williamson died on 19 January 1799 in Edinburgh at the age of sixty-eight and was buried in the Old Calton Cemetery. The Edinburgh Evening Courant printed an obituary for Williamson two days after his death. Like Kay’s dual portrait, the obituary confuses Williamson’s “considerable time among the Cherokees” with the Lenape, demonstrating how his captivity and kingship were received back home. He was a traveller and travel liar who masqueraded between worlds and helped shape the violent imaginary of the British public.

Williamson’s life story has puzzled many writers and scholars. Creative monographs such as Douglas Skelton’s Indian Peter: The Extraordinary Life and Adventures of Peter Williamson (2004) and Rosemary Linnell’s The Revenge of Indian Peter: The Incredible Story of Peter Williamson (2006) take much of Williamson’s narrative at face value. His transcultural identity and fabrication of Indigeneity are examined more critically in Linda Colley’s Captives: Britain, Empire, and the World, 1600–1850 (2002), Troy Bickham’s Savages Within Empire: Representations of American Indians in Eighteenth-Century Britain (2006), Tim Fulford’s Romantic Indians: Native Americans, British Literature, and Transatlantic Culture, 1756–1830 (2006), and Robbie Richardson’s The Savage and the Modern Self: North American Indians in Eighteenth-Century British Literature and Culture (2018). But the leading expert on Williamson is Timothy Shannon. The present biography is indebted to Shannon’s Indian Captive, Indian King: Peter Williamson in America and Britain (2018) and his critical edition of French and Indian Cruelty (2023), which uncover vital information about Williamson’s life and separate fact from fiction. Scholars have yet to fully consider his satirical influence on lieutenant Obadiah Lismahago, the Scottish colonial soldier and Indigenous storyteller from Tobias Smollett’s novel, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771). For a brief comparison, see Tara Ghoshal Wallace, “‘About savages and the awfulness of America’: Colonial Corruptions in Humphry Clinker,” Eighteenth Century Fiction 18, no. 2 (Winter 2005–2006).

Dictionary of National Biography (1885–1900)

WILLIAMSON, PETER (1730–1799), author and publisher, son of James Williamson, crofter, was born in the parish of Aboyne, Aberdeenshire, in 1730. When about ten years of age he fell a victim to a barbarous traffic which then disgraced Aberdeen, being kidnapped and transported to the American plantations, where he was sold for a period of seven years to a fellow countryman in Pennsylvania. Becoming his own master about 1747, he acquired a tract of land on the frontiers of the same province, which in 1754 was overrun by Indians, into whose hands Williamson fell. Escaping, he enlisted in his majesty's forces, and after many romantic adventures was in 1757 discharged at Plymouth as incapable of further service in consequence of a wound in one of his hands. With the sum of six shillings with which he had been furnished to carry him home, he set out on his journey, and reached York, where in the same year he published a tract entitled 'French and Indian Cruelty exemplified in the Life and Various Vicissitudes of Peter Williamson … with a Curious Discourse on Kidnapping.' Arriving in Aberdeen in 1758, he was accused by the magistrates of having issued a scurrilous and infamous libel on the corporation of the city and whole members thereof. He was at once convicted, fined, and banished from the city, while his tract, which had passed through several editions in Glasgow, London, and Edinburgh, was ordered to be publicly burnt at the Market Cross. Williamson brought an action against the corporation for these proceedings, and in 1762 was awarded 100l. damages by the court of session. He was also successful in a second suit brought in 1765 against the parties engaged in the trade of kidnapping.

Williamson settled in Edinburgh, where he combined the occupations of bookseller, printer, publisher, and keeper of a tavern, 'Indian Peter's coffee room' (Fergusson, Rising of the Session). In 1773 he issued the first street directory for Edinburgh. In 1776 he engaged in a periodical work after the manner of the 'Spectator,' called the 'Scots Spy, or Critical Observer,' published every Friday. This periodical, which is valuable for its local information, ran from 8 March to 30 Aug., and a second series, the 'New Scots Spy,' from 29 Aug. to 14 Nov. 1777.

About the same time Williamson set on foot in Edinburgh a penny post, which became so profitable in his hands that when in 1793 the government took over the management, it was thought necessary to allow him a pension of 25l. per annum. Williamson died in Edinburgh on 10 Dec. 1799. He married, in November 1777, Jean, daughter of John Wilson, bookseller in Edinburgh, whom he divorced in 1788. A portrait of Williamson is given by Kay (Original Portraits, i. 128), and another 'in the dress of a Delaware Indian' is prefixed to various editions of his 'Life.'

In addition to 'French and Indian Cruelty' and the 'Scots Spy,' Williamson was author of: 1. 'Some Considerations on the Present State of Affairs. Wherein the Defenceless State of Great Britain is pointed out,' York, 1758. 2. 'A brief Account of the War in North America,' Edinburgh, 1760. 3. 'Travels of Peter Williamson amongst the different Nations and Tribes of savage Indians in America,' Edinburgh, 1768 (new edit. 1786). 4. 'A Nominal Encomium on the City of Edinburgh,' Edinburgh, 1769. 5. 'A General View of the whole World,' Edinburgh, n.d. 6. 'A Curious Collection of Moral Maxims and Wise Sayings,' Edinburgh, n.d. 7. 'The Royal Abdication of Peter Williamson, King of the Mohawks,' Edinburgh, n.d. 8. 'Proposals for establishing a Penny Post,' Edinburgh, n.d.

Among the works issued from his press were editions of the Psalms in metre (1779), of Sir David Lindsay's poems (1776), and of William Meston's 'Mob contra Mob.' The 'Life and Curious Adventures of Peter Williamson' (a reprint with additions of his 'French and Indian Cruelty') was published at Aberdeen in 1801, and proved very popular, running through many editions, and appearing also in an abbreviated form as a chapbook.

[Printed papers in Peter Williamson v. Cushnie and others, 1761-2. v. Fordyce and others, 1765-1768, v. Jean Wilson, 1789; Robertson's Book of Bonaccord, pp. 9l-3; Kay's Original Portraits, i. 131-9; Blackwood's Magazine, lxiii. 612-27; Chambers's Miscellany, vol. ii.; Lang's Historical Summary of Post Office in Scotland, p. 16; Scottish Notes and Queries, iv. 39, v. 87, ix. 29, 47.]

P. J. A.