Rose Street

Pat Rogers, University of South Florida

April 2025

This was a short zigzag of a passageway in the parish of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden. Within the jumbled road network of the surrounding district, it made its crablike way towards New Street. It has been succinctly described as “a dirty and somewhat circuitous street, between King Street and Long Acre, for the most part cleared, or absorbed, in forming Garrick Street” (Wheatley and Cunningham). Built from about 1623, it would make a striking contrast in the following decades to the stately surroundings of the nearby square, which featured Inigo Jones’s famous piazza and the newly fashionable Palladian style of his design for the parish church. In 1720 John Strype termed the street “indifferent well built and inhabited.” By the Victorian era, the immediate district had gone down in the world: George Augustus Sala wrote of how “Thoroughfares, almost inconceivably tortuous, crapulous, and infamous, debouch upon New Street. There is that Rose Street, or Rose Alley, where, if I be not wrong in my topography, John Dryden, the poet, was waylaid and cudgelled; and there is a wretched little haunt called Bedfordbury, a devious, slimy little reptile of a place, whose tumble-down tenements and reeking courts spume forth plumps of animated rags.” An unprepossessing road named Hart Street running eastwards was renamed Floral Street on honour of the nearby flower market, which remained on the site until 1974.

Despite losing some of its lower leg when Garrick Street was sliced through in the middle of the nineteenth century, Rose Street survives as a cramped thoroughfare running in the direction of King Street on the north-western edge of Covent Garden. On one side, there still winds an especially narrow alley, known in earlier days as Glastonbury or Lassingby’s Court, today named Lazenby Court. It lies behind the Lamb and Flag, a hostelry dating from the 1770s as the Cooper’s Arms. Here a plaque refers to the two best remembered items in the annals of Rose Street: one is the death of the satirical author Samuel Butler at his home here on 25 September 1680. The other is the mugging of John Dryden, mentioned by Sala. This took place a year earlier, on 18 December, when three men launched a vicious attack on the poet laurate, beating him repeatedly as he walked near his home along what reports of the time called Rose Alley. The plaque at the Lamb and Flag claims that the assault came at the instance of Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth (1649–1734), the French mistress of King Charles II. It is more likely that the true instigator was the poet and rake John Wilmot, second Earl of Rochester (1647–80), who had literary as well as political and personal reasons to quarrel with Dryden. According to one version of events, the injured party offed a considerable reward of £50 for the identity of those involved, but they have never been reliably identified. Rochester died just seven months later.

The street figures fairly often in the proceedings of the Old Bailey court house, once as “a small bye Street.” In 1689 we read of a murder committed in a “reputed Bawdy-House in Rose street at Long-Acre,” kept by Sarah Tayler. She was one of the three defendants accused of the crime as principal or accessory, but despite “a very weak Defence” by Tayler, it transpired that “after a full and large Hearing, they were all acquitted.” In 1739 two female shoplifters were plucked from custody when the coach transporting them to the roundhouse was stopped when it strayed “down Rose Street, into an Alley where a House had been burnt down,” enabling a mob to assemble in St. Martin’s Lane to carry out the rescue. A case from 1751 that involved the Bow Street magistrate, Henry Fielding, in 1751 concerned two women accused of the capital crime of coining. Much of the action took place around Russell Street, Covent Garden and Drury Lane, but the first witness to their alleged offence of passing counterfeit money kept a chandler’s shop in Rose Street. Again the defendants were acquitted. In later years, Henry’s brother Sir John Fielding had a part in detecting crimes associated with the street, for example a theft of carpets in 1773. Their long-time colleague on the bench Saunders Welch took a hand in other cases.

Further cases of theft and occasionally coining are scattered through the records well into the nineteenth century. Well stocked with alehouses, the vicinity offered opportunities for various offences against the law. It did not help that St. Paul’s parish watch (like that of its neighbours, to be fair) contained many a Dogberry: “Being examined before a committee of the House of Commons in March 1735/6 a parishioner said ‘That he, often suspecting the Watchman near his House to be asleep, ordered his Servant, one Night, to take away his Lantern; which he did, without the Watchman’s Knowledge; and that he has often met the said Watchman crying the Hour, without either Lantern or Staff, only a Walkingstick.’”

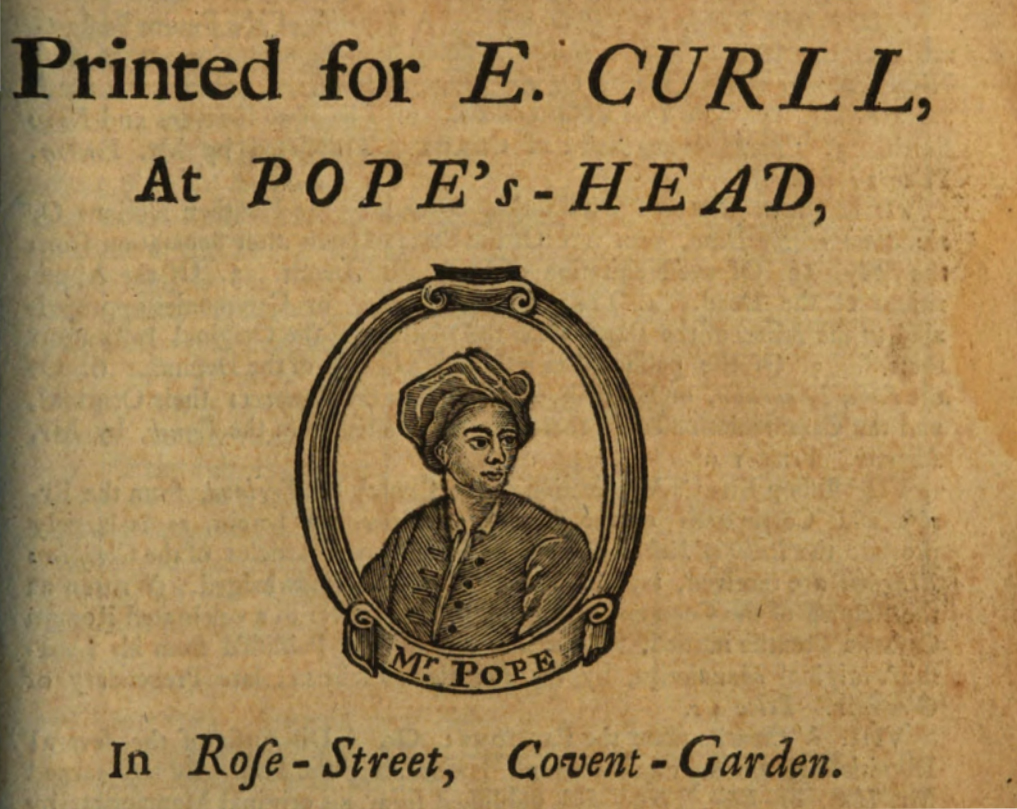

A further connection with the world of books, in addition to those of Dryden and Butler, is less celebrated. Rose Street was the last base of the notorious publisher Edmund Curll (1683–1747), who moved his shop there in 1734 from its former locations on the other side of Covent Garden. His imprint “at the Pope’s Head in Rose Street, Covent Garden” became familiar over the next thirteen years. When he died in 1747, his body was carried less than a hundred yards for burial at St. Paul’s—now known as the actors’ church because of its many links with the theatrical profession, and a suitable resting place for such a consummate public performer.

In this location the bookseller was close to members of his target audience, owing to the presence of there of playhouses, taverns, coffee houses and other places of entertainment, quite apart from the thriving sex industry. Moreover, Rose Street was in easy reach of fashionable areas in St. James’s, the more raffish artistic quarter around St. Martin’s Lane and Soho, and the highly concentrated population of St. Giles’s, immortalized by Hogarth in his portrayal of Gin Lane (1751), where the artist stated there was “not a house in tolerable condition but Pawnbrokers and the Gin shop.” All in all, few addresses lay closer to the heart of the capital—demographic, cultural, commercial or legal—than this modest back street nestling behind the proud frontage of Covent Garden.